By Liz Melton

[box]Introduction[/box]

Over 13 million Americans are currently plagued by urogynecological afflictions1—an escalating epidemiological concern. Lamentably, two critically important issues in women’s health, stress urinary incontinence (SUI) and pelvic organ prolapse (POP), are scarcely referenced in popular literature, let alone mentioned in conversation. A silent and growing pandemic, the prevalence of SUI symptoms among women over the age of 20 has grown to a staggering 49.6%2. Furthermore, the average American woman has an 11.1% lifetime risk of undergoing an operation for pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence, excluding the large proportion of cases that necessitate reoperation3. Skyrocketing numbers of procedures will be infeasible to accommodate in the medical sphere. Accordingly, research is essential to finding SUI and POP cures. This article delves into the urogynecological field of study, highlighting contemporary research approaches such as analysis of ultrasound images, and biomechanical assessment with sensor probes, each playing a role in understanding pelvic floor function.

[box]Stress Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Organ Prolapse[/box]

The International Continence Society has deemed urinary incontinence “the complaint of any urinary leakage”4. SUI exten

ds that definition to incorporate involuntary loss of urine subsequent to physical exercise, coughing, sneezing, or laughing5. Incontinence risk increases with age6, and complications such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, parity, and prior hysterectomy contribute to incontinence susceptibility4. Pelvic organ prolapse, on the other hand, is defined as the descent of one or more of: the anterior vaginal wall, the posterior vaginal wall, and the apex of the vagina (cervix/uterus) or vault (cuff) after hysterectomy5. Risk factors for POP consist of age, body mass index, and higher vaginal pari

ty. A study from the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1997 also estimates that per 10,000 women, whi

te women had a threefold higher rate of surgery for POP compared with African American women (19.6 vs 6.4,

respectively)4. Because pelvic organ prolapse can occur in association with lower urinary tract dysfunction, debilitated abdominal muscles are outcomes of POP, as well.

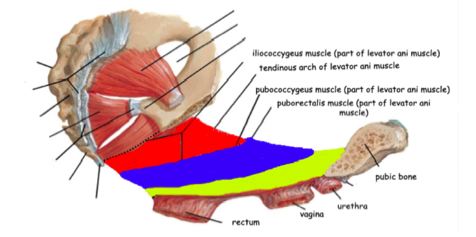

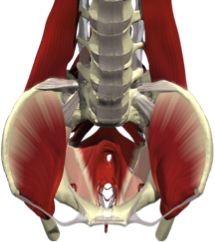

Healthy individuals will voluntarily, or involuntarily, activate abdominal muscles in order to reign in potential leakage during vigorous movement. Unfortunately, injury to lower abdominal muscles is common following childbirth, retarding the function of major abdominal muscle groups7. In turn, slower and weaker contraction rates compromise the ability of an SUI patient to restrain urinary leakage, and also increase her probability of acquiring POP. Delineating pelvic structures pertinent to SUI and POP elucidate how pelvic floor ailments are due to damage to levator ani (LA) muscles. This set of muscles, located in the abdominal cavity, consists of the pubococcygeus, puborectalis, and iliococcygeus. LA muscles snake tightly around the entire abdomen area, maintaining urethra and pelvic structure position, as can be visualized by the coronal view of Figure 2. All three muscular components also actively prevent urethral leakage (see Fig. 1). Women with POP and SUI have levator ani and periurethral muscle denervation and decreased neuropeptide activity4.

[box]Latest Research[/box]

A veritable “toolbox” of research methodologies, the latest modus operandi include: (a) acquisition and analysis of streaming ultrasound images so that non-invasive biomechanical measurements can be made, (b) application of a biosensor probe which estimates pelvic floor function in terms of force of contraction, and (c) biomechanical evaluation of vaginal tissue to map tissue elasticity relative to hormonal consequences of maturity and childbirth. An even more alluring prospect, obtaining tissue from patients undergoing POP or SUI surgery, facilitates production of regenerative adult stem cells, preventing further vaginal tissue wear and tear due to aging. In summary, this article presents an assemblage of innovative instrumentation, which can eventually be used by the clinical community to enable the prevention and treatment of SUI and POP[J4] .

Ultrasound images serve as models through which to observe LA muscles in action. Contrasting muscle displacement during voluntary and involuntary contractions of continent versus incontinent patients, and POP versus non-POP patients, is a prime diagnostic, research, and healing tool for SUI and POP victims8. Clips of ultrasound imaging can certainly expose displacement of pelvic structures in a 2-

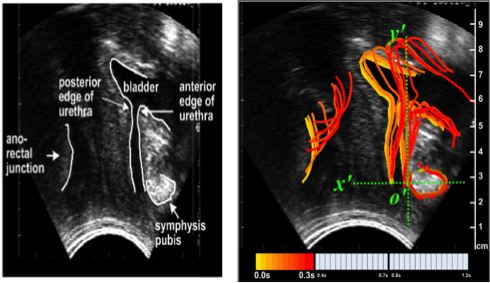

D projection. Nonetheless, given the incredibly short amount of time during which a reflex arc functions, an observer will not fully capture even a 2-D trajectory. To that end, this paper underscores two techniques of revolutionary 3-D, as opposed to 2-D, image creation: sequential ultrasound images and color representation of time to illustrate the LA muscles and pelvic organ behavior in real-time.

Muscle displacement in response to reflexes, such as coughing, and voluntary actions, such as levator muscle contractions, are springboards for exhibiting these two 3-D conversion forms. Numerous chronological images obtained from a stream of ultrasound film can endow a time-sensitive, segmented visualization of muscle displacement. 3-D illustration is conducive to visualizing precise organ position at any point in time. A second 3-D displacement portrayal revolves around a sole ultrasound image. Time is displayed in colors arising in succession: each color denotes consecutive outlines of displacement (observed in Figure 3)8. Applications of time-color depictions of 3-D ultrasounds are crucial to theorizing cures for SUI and prolapse victims.

Although ultrasound relays spatial statistics vital to the realm of urogynecological exploration, ultrasound fails to convey intrinsic strength of intact levator ani muscles, thereby inhibiting comparison to the incapacitated LA muscles of SUI and POP sufferers. Complementing the functionality and convenience of ultrasound imaging, innovative biomechanical probes have become prominent tools in urogynecological research9. Researchers can quantify pelvic floor muscle function in terms of force of contraction through sensors located on alternate sides of intravaginal probes. Missing from ordinary ultrasound readings, biosensors document the force produced in voluntary and involuntary contractions of the LA muscles. These data may warrant physical therapy exercises to alleviate diminished muscle tone sustained by SUI and prolapse. Evaluation of levator ani muscle potency is analogous to tracking an athlete’s progress in reaching a targeted bench press goal. By quantifying force dynamics of the pelvic floor, physical therapists may quantitatively assess patient growth over time, in the hopes of diminishing SUI and prolapse symptoms.

By using the discussed technologies, researchers are able to acquire a corporeal idea of biomechanics from ultrasound and biomechanical force statistics from vaginal probes. However, researchers are left with little to no knowledge on the characteristics of pelvic floor tissue. Information regarding quality of tissue is central to comprehending how vaginal tissue subsides to the brink of POP and SUI. Tactile Resonance Sensors, a predominant brand of tool on the urogynecological research market, are the compelling, new-age equivalent of doctor palpation. Able to typify tissue of patients with urinary prolapse, Tactile Sensors are equipped to measure parameters of contact between sensor and object of interest—in the domain of SUI and POP research, vaginal wall tissue. Fundamentally, Tactile Sensor software controls movement of a resonating sensor against vaginal wall tissue samples, collects data streaming from the sensor, and converts data into a visual map demonstrating elasticity discrepancies in tissue between patients and healthy controls.

[box]Preliminary Data[/box]

In accordance with IRB standards, recent experimenters have procured small sections of tissue from subjects’ vaginal walls. Although this process appears invasive, subjects who already undergoing surgery for prolapse or urogenital cancer are intentionally chosen. Following vaginal wall tissue acquirement, the bulk of tissue is dissected into even smaller pieces (usually two or three), and frozen at -80°C to capacitate future analysis via the Tactile Resonance Mapping System. The substantiated evidence available demonstrates that Young’s modulus, a measure of elastic material stiffness (the ratio of the uniaxial stress over the uniaxial strain), of vaginal tissues is higher (stiffer tissues) in women with POP compared to controls, suggesting that tissues from women with POP have

lost the ability to recoil10. Just as the force of a shooting rubber band is dependent on its ability to recoil, decreased elasticity (or decreased recoil) of vaginal wall tissue will generate less force. Hence, dwindling elasticity of vaginal wall tissue in elderly women permits the gradual loosening of pelvic structure. Even from this preliminary data10, it

is clear that there is considerable potential for broadening the scope of the Tactile Mapping Resonance System, and for formulating and testing countless new hypotheses11. Parallel experiments may illuminate the possibility of endogenous hormones having a direct effect on tissue elasticity, or may provide new data integral to developing reconstructive approaches with synthetic materials. Finally, a long-term prospect is growing regenerative adult vaginal wall stem cells to substitute for frequently unsuccessful SUI and prolapse surgeries.

[box]Conclusion[/box]

In fact, current surgical treatment for SUI in particular is, at best, empirical in nature and has major limitations that often require reoperations. Even more disconcerting is the lack of known preventative measures and risk factors for POP, resulting in both extremely unnerving day-to-day sensations, and often eventual hysterectomy. Investigations aiming to better understand the mechanisms responsible for both SUI and POP will yield more fruitful, physical therapy-like cures. Recently, urogynecological pioneers have conceived a “toolbox” of modern methods to evaluate and further comprehend the pelvic floor, comprised of: streaming time-modified ultrasound images, force computing biosensor probes, and mapping tissue elasticity distribution via Tactile Resonance Sensors. By identifying functional anatomy of tissue and muscles, elastic properties, and cellular constitution, researchers hope to generate a framework for an approach to treat SUI and prolapse patients. On the very forefront of current medicine, urogynecological research ultimately aspires to promote better diagnosis understanding and cures for the unspoken epidemics of tress urinary incontinence and prolapse.

References:

1. Sung VW, Rogers ML, Myers DL, et al. National trends and costs of surgical

treatment for female fecal incontinence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007;197(6):

625, e1-5.

2. Dooley Y, Kenton K, Cao G, et al. Urinary incontinence prevalence: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Urol 2008;179(2): 1311–1316.

3. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, Bergstrom JO, Colling JC, Clark AL. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89(4):501-506.

4. Sung, Vivian W., and Brittany Starr Thompson. “Epidemiology of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction.” Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics 36.3 (2009): 421-33. Pubmed.gov. Web. 4 June 2011. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

/19932408>.

5. Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardisation of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardisation subcommittee of the International Continence Society. Urology. 2003;61(1):37–49.

6. Delaney K, et al. Urinary incontinence in US women. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:537–42.

7. Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, et al. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(11):1311–6.

8. Constantinou, Christos, Daniel Korenblum, and Bertha Chen. “Visualization of Pelvic Floor Reflex and Voluntary Contractions.” Pubmed.gov. National Institutes of Health, 2011. Web. 4 June 2011. <http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21335777>.

9. Constantinou CE, & Omata S. Novel and directionally sensitive probe: design and bio-mechanical specifications. In: Incontinence: Engineering Challenge. Proceedings of Institute of Mechanical Engineers, London, 2003

10. “Biomechanical properties of anterior and posterior vaginal wall in pre- and postmenopausal women with pelvic organ prolapse” Guest Speaker. The thirty-sixth Annual Meeting of the International Urogynecological Association, Lisbon, Portugal, June, 2010.

11. Lindahl OA, Constantinou CE, Eklund A, Murayama Y, Hallberg P, Omata S. J Med Eng Technol. 2009; 33 (4): 263-73