LINGUISTICS DEPARTMENT - STANFORD UNIVERSITY

An Invitation to CALL

Foundations of Computer-Assisted Language

Learning

Home | Unit 1 | Unit 2 | Unit 3| Unit 4| Unit 5| Unit 6 | Unit 7 | Unit 8 | Supplement

An Invitation to CALL

Unit 7: CALL Learner Training

OVERVIEW

CALL has given us some amazing possibilities for improving language learning.

However, these possibilities create a problem. Absent a teacher, students using

computers are typically given more control over their own learning. Due to the

newness of computer environments and the range of choices in many CALL

applications, they are arguably unprepared to take on this responsibility. The

result is that students may not use the computers in ways that are effective for

achieving language learning objectives, and it is even less likely that they

will use them in ways that are most effective.

One way out of this dilemma is to spend time training learners in dealing appropriately with this new environment. In the process, we may be able not only to help them with their CALL use, but also help them in general to become more effective autonomous learners. Surprisingly, this is not a well-developed area of CALL. However, it is important enough in my experience to warrant significant attention. As Jones (1999) remarked with respect to using CALL materials in self-access centers, "it seems very likely that for most students CALL will need more learner training and more of the teacher’s presence than any other operations..."

Before continuing, let's consider three alternatives to CALL learner training...

One solution is to try to build software in such a way that it adapts to the learner on a number of different levels: language proficiency, computer proficiency, learning style, topical interest, motivational type and intensity, and so on. This was an early promise of CALL software; however, arguably we have not even come close to realizing such a program, and the degree of software-directed adaptation remains low or non-existent in currently available materials.

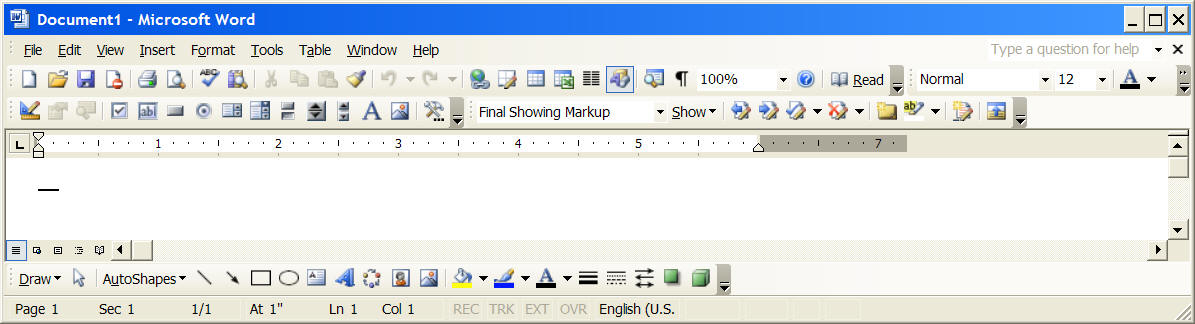

A second alternative is to take the philosophical position that learners have a right to self-discovery and that left alone they will naturally move to the strategies that work for them and that are consonant with their learning style. This would mean that given a tutorial program with a set of help options, they would make use of the ones that are most efficacious for them and ignore the others. It seems highly unlikely that this would be the case for most students. For example, you probably know how to use Microsoft Word (or some similar word processing application). How many of its features do you really know how to use? Open Word ( an example from Word 2003 for Windows appears below, but any version will suffice) now and look at the top level. Do you know what's under File, Edit, View, Insert, etc.? Do you know what the underscore means in commands like File?

If you pull down those menus and find some features you are uncertain about or never knew existed, this is a good demonstration of how hours (hundreds of hours in some cases) of contact alone with a piece of software will not automatically lead to efficient use. (By the way, if you already know all this stuff, you're in the minority). Evidence that a high percentage of today's university students do not have the skills they need to use computers effectively for language learning can be found in Winke & Goertler (2008).

A third alternative is to acknowledge that learners would profit from training but that it's just too much trouble to train them since it obviously takes a lot of time away from other aspects of language learning and there's no guarantee it will be successful. This may indeed be the case in some instances, but this should be determined on a case by case basis, using at least a rough cost vs. benefit analysis.

TECHNICAL TRAINING

Let us proceed under the assumption that it is worth the trouble to do at least some training. What do we need to do?

Training can be divided at least into two areas: technical and pedagogical (you may recall that this was the same division as for teachers in Unit 1). Technical training naturally includes general computer literacy (which can be a major issue or not depending on your setting and students), but of greater interest here is learning technical skills and knowledge of particular value to language learning.

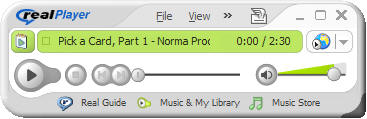

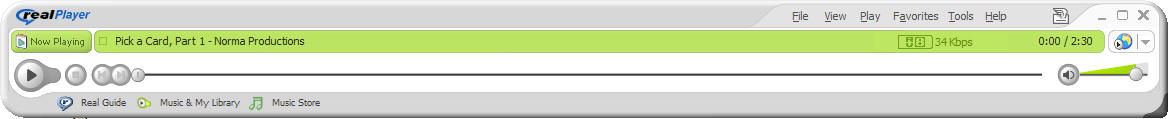

Here is one example: most audio/video players, for instance (Real, QuickTime, Windows Media), often have a default setting that is small:

But by dragging the bottom right corner, the player can be stretched. This gives much finer control when using the slide bar to repeat a segment.

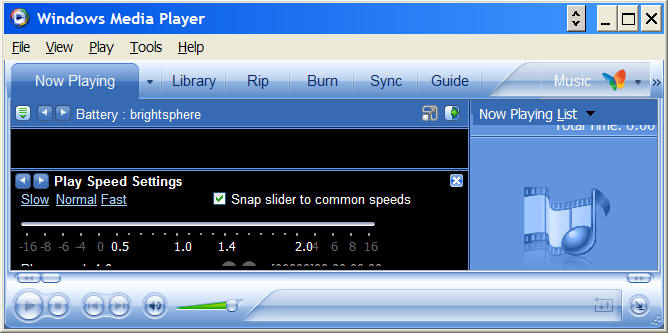

Here's another example: recent versions of Windows Media Player have a "play speed" control that allows learners to slow down (or speed up) sound files (accessed through View > Enhancements > Play Speed Settings). A lot of students are unaware of this. Although some previous research suggested that listening at a slower speed does not necessarily aid comprehension, one key study (Zhao, 1997) showed that when students are given control over the speed, rather than having it controlled by the teacher, their comprehension improves. For some students at least, a slower speed may make linkages across word boundaries more noticeable, and it may be quite helpful for certain tasks and types of material to have this additional control.

These are just two of many instances of technical knowledge that can potentially be of help to language learners.

PEDAGOGICAL TRAINING

In a 2004 paper (Hubbard, 2004), I make a case for giving training not just on technical aspects but also on pedagogical ones, that is, how to use the tutorial software or tool effectively to meet specific learning objectives. To this end, I offer a set of five principles for learner training, summarized below.

Of course, in order to be effective at training students, it is necessary to thoroughly analyze the software, task, or activity you are assigning. You need to be sure that you can make the connections between given actions and learning objectives before you can expect your students to do so on their own.

An updated version of this framework is currently under development. It acknowledges three domains for training instead of two--technical, strategic, and pedagogical--by moving some of what was previously considered pedagogical training to the more commonly recognized area of strategy training. See www.j-let.org/~wcf/proceedings/d-060.pdf for a brief description of that model.

STANDARDS: One way of improving especially the technical competence of learners is through general proficiency training in this area. The International Society for Technology in Education (http://www.iste.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=NETS) has promoted both teacher and student standards (primarily focused on the US K-12 constituency), and TESOL has also produced a technology standards framework for students and teachers aimed internationally at all levels. Both organizations acknowledge the responsibility of teacher education programs and educational institutions to ensure students and teachers meet these standards. A description of some of the TESOL Standards and how they were developed is online at http://www.j-let.org/~wcf/proceedings/d-025.pdf, and the Standard themselves are available at https://iweb.tesol.org/Purchase/ProductDetail.aspx?Product_code=EBK1.

LEARNER TRAINING MATERIALS: Union County College - CALL Suggested Strategies Website http://staff.ucc.edu/alc-paez/esl/call/index.htm. This site has materials for both technical and pedagogical training for the applications used by the English program at UCC. Examples of materials used in learner training can also be found at my advanced listening website: www.stanford.edu/~efs/693b.

SUGGESTED ACTIVITY: Go to a website like www.esl-lab.com or www.elllo.org. First, familiarize yourself with the main parts of the site (or all of it). Then try to determine 1) what basic technical training students might need to use the site effectively; 2) what more advanced technical training would be helpful; 3) how pedagogical training would connect to this, both site-specific and generalized; 4) finally, how might you "teach" this information to them?

REFERENCES

Hubbard, P. (2004). "Learner Training for Effective Use of CALL" in Fotos, S. and Browne, C. (eds.) New Perspectives on CALL for Second Language Classrooms. Mahwah NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Jones, J. (1999). "Language learning, technology and development: the essential interaction between teachers and students." Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Language and Development: www.languages.ait.ac.th/hanoi_proceedings/jeremy.htm .

Winke, P. & Goertler, S. (2008). Did we forget someone? Students’ computer access and literacy for CALL. CALICO Journal, 25(3).

Zhao, Yong (1997). 'The effects of listeners’ control of speech rate on second language comprehension." Applied Linguistics, 18,1: 49-68.