As the field of nanoscience grows, more and more emphasis is being placed on bottom-up construction; that is, creating individual molecules or structures on the micrometer scale from the individual atoms that comprise them.[1] This method provides two major benefits: one, we can construct smaller and smaller structures for our use; and two, the strength or capabilities of some materials are enhanced as its atoms become increasingly organized in structure.[2] Unfortunately, the bottom-up process can be very difficult, particularly when trying to create molecules from their constituent atoms- most molecules and materials, although very small, contain hundreds, even thousands of atoms. Creating such an atom piece-by-piece, like some of today’s current methods, would cost an incredible amount of time. Fortunately, a revolutionary technique of assembling nano- and micro-scale materials that utilizes the concepts of bio-assembly has recently been discovered.[3]

Viral Bioassembly

This method utilizes viruses to construct incredibly well-ordered materials. The pursuit of creating perfectly crystalline materials was initially inspired by the shell of an abalone, which is composed of 98% calcium carbonate, also know as chalk. Yet, the shell is three thousand times stronger than chalk. How can this be? The secret lies in the fact that the calcium carbonate molecules are very well ordered in the structure, and therefore the shell becomes much stronger than if its atoms were unordered.[4]

These viruses are created using specific genomes of the DNA[5], a process which allows the virus to organize inorganic, organic, and biological materials into defect-free structures.[6] This capability is invaluable, particularly in an age of growing electronics, optics, and magnetism, fields that all require high precision, well-ordered materials at increasingly smaller sizes.[3] Due to their small size, viruses make perfect substances for creating small structures.[4]

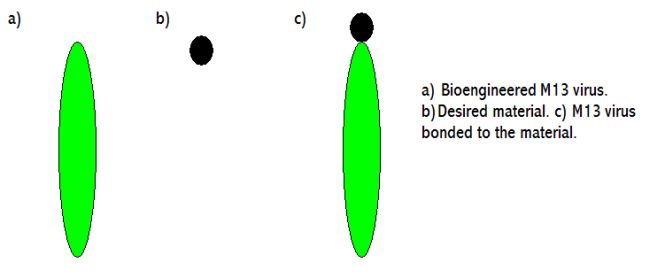

Figure 1, adapted from Lee et al.[3]

The Process

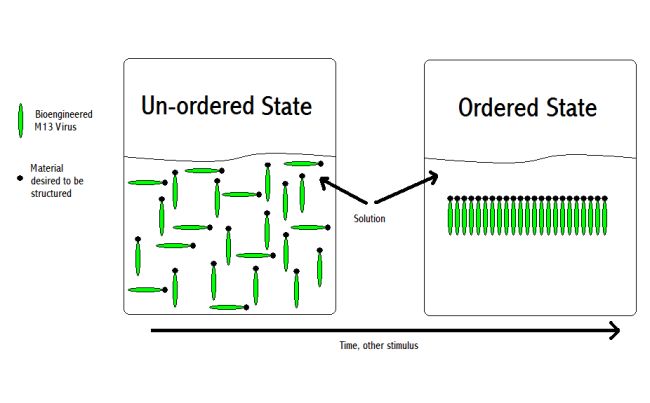

The virus most commonly used in this process is a genetically-engineered form of the M13 virus,[3] a virus safe for both humans and the environment.[4] Through genetic-engineering, the adapted M13 virus is capable of bonding itself to the individual atoms or molecules of nearly any substance desired (Fig. 1).[3] Once the virus has bonded with these atoms, it aligns within a solution with other M13 viruses that are also bonded to the same material.[3] What results from this process is a high-ordered structure consisting of the material the virus was bonded with- in essence, a self-assembled nanostructure (Fig. 2).[3]

Figure 2

Advantages

This process can easily be scaled up to create larger and larger structures, since it all takes place in a solution.[4] Also, since viruses are very malleable as a solution, many different general shapes and designs can be created, such as a meter long nanowire.[4] Furthermore, viral bio-assembly produces a useful quantity of the created material, whereas in other bottom-up construction processes create relatively little of the final structure.[4]

Disadvantages

Unfortunately, viral bio-assembly is very time consuming. Many hours are spent in the lab analyzing millions of viruses in a search for the one virus that is capable of attaching itself to the desired material.[4] In addition, it is currently very difficult to control the absolute size and geometry of the resulting structure (only the general size can be controlled).[5]

Conclusion

The future of the use of viruses in bio-assembly is vast. As further research is conducted, researchers expect to be able to maintain more control over the overall process.[5] Until then, viruses will continue to play an important role in the development of bio-assembly.