Table of contents

With modern machine learning (ML) and data science workflows, it is common practice to use powerful servers that can provide the necessary horsepower for heavy computations instead of your local machine. These remote servers (also called headless machines) operate without a monitor, keyboard or mouse. You control them purely through the network.

In my research, I use my laptop just as a gate to tunnel into my lab’s servers. All my compute-intensive workloads for training deep learning models are done on remote servers. I even host my Jekyll blog server on my desktop, using it as a headless machine accessed through my laptop. I have it set up such that all my python scripts, Jupyter notebooks, Jekyll code run on servers (either headless lab servers or my desktop server), but their corresponding GUI (graphical user interface) shows up on my laptop.

This is possible through the use of SSH Tunneling or SSH Port Forwarding. In this post, I’ll walk you through the different ways you can accomplish this for your own work. You can directly skip ahead to the use cases if you just want to know how to use this practically. To understand how it works in detail, read on!

SSH: Secure Shell

The SSH (Secure Shell) Protocol provides a secure (encrypted) connection over not-necessarily-secure networks. It’s your bread and butter if you work with any kind of remote system: dedicated servers, the cloud or a even a data center.

An SSH connection involves: (1) an SSH Client that initiates connections to remote machines, and (2) an SSH Server that listens to and accepts incoming connection requests from different client machines.

Before we go into the details of tunneling, let’s understand some background terminology.

Networking Background (err… Jargon)

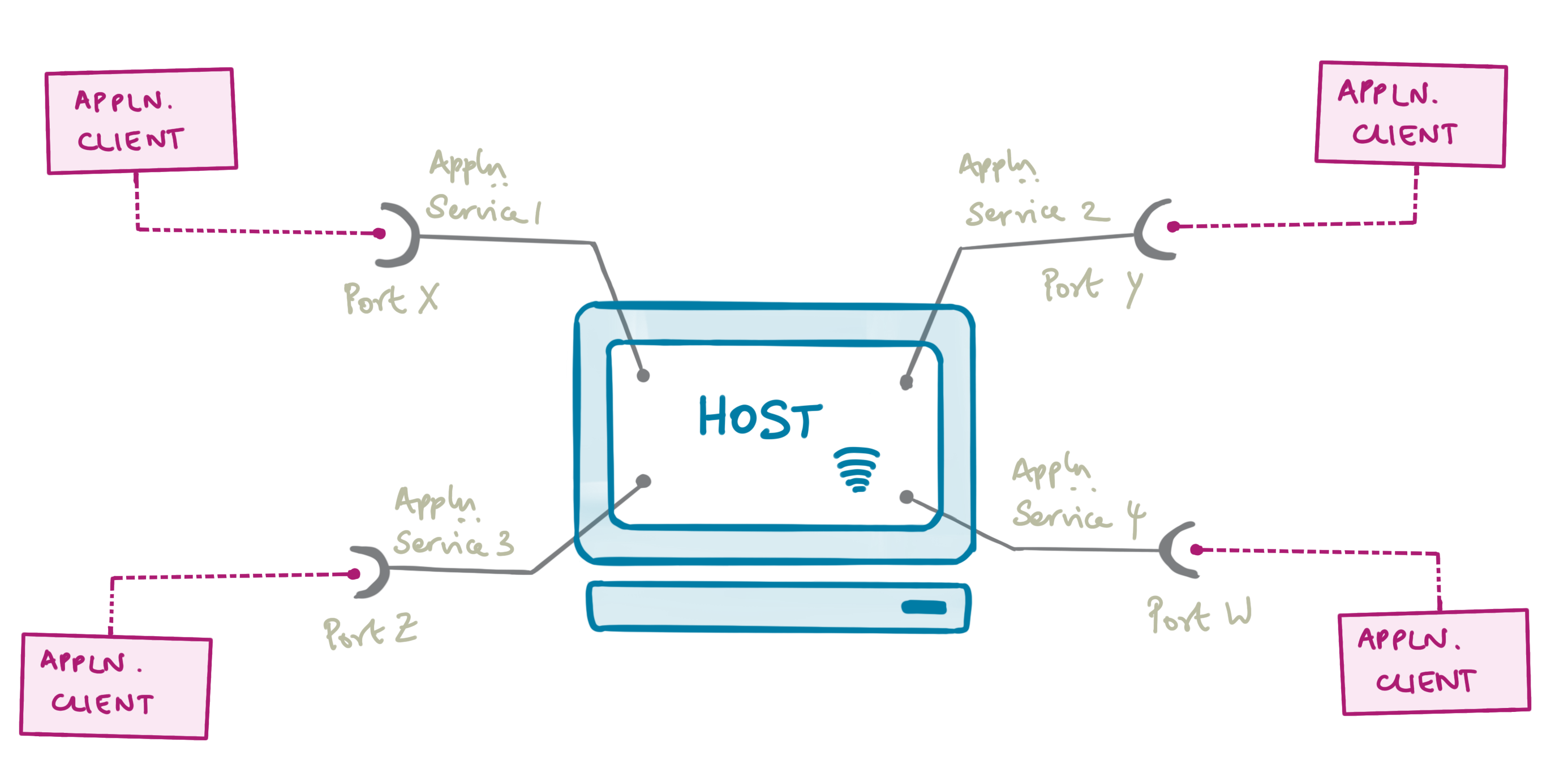

A computer or a machine is oftentimes referred to as a host. A host can have multiple network interfaces, each with its own IP address. For the purposes of this post, I use ‘host’ synonymous with a computer’s network interface having a dedicated IP address.

While a host is a single entity, it can offer multiple services (e.g. web server, Jekyll server, mail server, etc). Each service is allowed to pick a port under the TCP protocol, a number between 0 and 65535, to distinguish it from other services1.

The services listen to their particular port, waiting for clients to initiate connections to them. Once the requests are accepted, the clients connect to the target port corresponding to that of the service. The combination of an IP address and a port number constitutes a socket3.

\(\dagger\) The client uses a port (source port) too – it is not standard and is randomly assigned

Any connection can be uniquely defined by a pair of source socket\(^\dagger\) and destination socket. Thus, multiple clients can connect to the same target at once but the connections are unique. For a connection attempt to succeed, an application must be listening on the destination socket.

Port Forwarding

SSH Port Forwarding (or SSH Tunneling) is a mechanism that tunnels client application ports to the application server via an SSH connection2.

\(\dagger\) Port numbers < 1024 are reserved (e.g. SSH uses port 22). Choose high numbers for forwarded ports to avoid conflicts

A forwarded port means that a client connects to a target port different from the host service port. This target port is then forwarded to the host service port to create a two-hop connection with the host service\(^\dagger\) via SSH. It is typically used to circumvent standard firewalls, add encryption to services and open backdoors in networks.

Let’s break this down with some concrete examples, shall we?

\(\dagger\) Typically, one host will be local and the other remote

Consider two machines\(^\dagger\) – let’s call them Host A and Host B. Let’s assume an application server is running on Host B, listening for incoming client requests at Port W (Fig 3, left). To establish a secure connection with the application client running on Host A, we need to set up an SSH session between the two hosts.

Since we want an SSH tunnel instead of a direct connection (Fig 3, right) between the application client and the application server, we first have to select an unused port on the application client side, i.e., Port Z (say) on Host A. Then, we request SSH port forwarding from the socket (A, Z) to the server socket (B, W). Once we point the application client to the socket (A, Z) instead of its original target (B, W), we are set! The entire scheme is much easier to understand using a diagram (Fig 4).

It is important to note that there are two servers and two clients in any port forwarding connection:

- the application server

- the application client

- the SSH server

- the SSH client

It is common to assume that the applications are running on the same hosts as the SSH processes. This is certainly the case for most scenarios. However, in principle, either the application client or server (or both) could be on different machines, potentially involving as many as four hosts in a single forwarding3. While this situation is possible, it is usually not recommended for security reasons.

The rest of this post assumes you have SSH access to remote servers and are already familiar with SSH’ing into them using your laptop SSH client (OpenSSH for Linux & WSL, PuTTY for Windows, etc).

Local vs Remote Port Forwarding

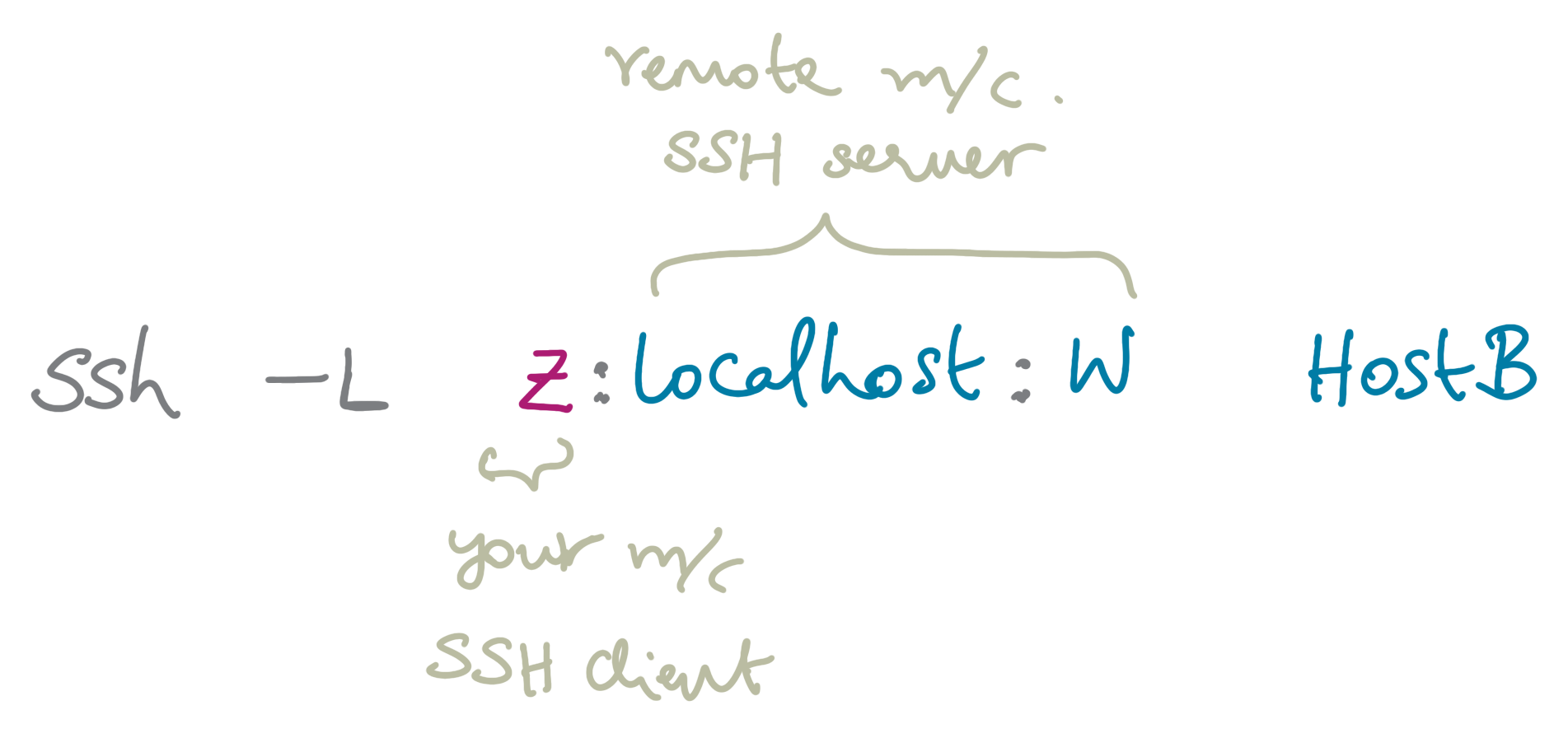

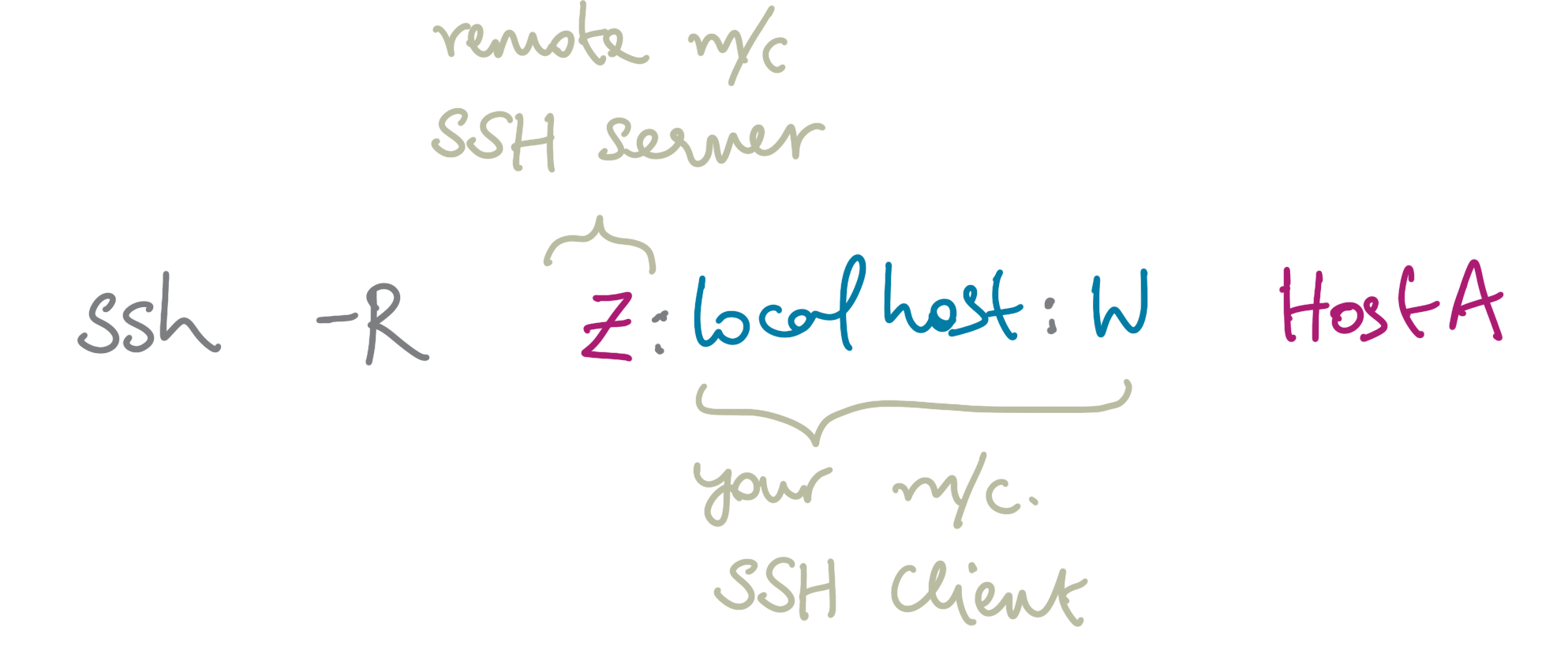

In practice, there are two options for port forwarding – local and remote, denoted by -L and -R repectively. Both options require us to specify the application client port, the application server IP address, the application server port and the SSH server destination. The command has the following architecture:

ssh -L (or -R) [bindAddress:]applnClientPort:applnServerIP:applnServerPort sshServerHost

So what does that option -L or -R do? The difference between them can be quiet subtle: when the application client is on the side of the SSH client, it is a local port forwarding scenario. Whereas, if the application server is on the side of the SSH client, it is a remote port forwarding scenario (Fig 5).

Figure 5: Local vs Remote port forwarding

Figure 5: Local vs Remote port forwarding

In our example scenario (Fig 5), the local port forwarding command would be:

And the remote port forwarding command would be:

Notice a few things here:

sshServerHost: You (the machine where you execute these commands) are ALWAYS the SSH Client. Thus, in the first case, you are SSH’ing into Host B whereas, in the second case, you are SSH’ing into Host A.applnServerIP: When the application server resides on the SSH Host, it is sufficient to specify localhost as the IP address. When it is on a different machine from the SSH process, we must write the actual IP address of the application server.The application client port (chosen port) will be on your machine (SSH Client) in the case of local port forwarding, and on the remote machine (SSH Server) in remote port forwarding.

bindAddress: This specifies the local machine’s IP address during local port forwarding. When left unspecified, it is considered to be localhost. In the case of remote port forwarding, bindAddress specifies the remote machine’s IP address that can access the local application server. When unspecified, it allows access from all remote machines with the correct port.

When to use what?

Here’re some simple guidelines to know when to use what kind of port forwarding:

When you want access to a server running on a different machine (e.g. a jupyter lab instance, a database server on the cloud, a jekyll server running on a remote machine) using clients in your local machine (e.g. browser), you use local port forwarding.

In specific instances when you are running a server on your local machine (e.g. a web app served from your machine, a router configuration from your localhost) and want to provide access to other hosts (e.g. a collaborator, a system administrator), you use remote port forwarding.

Forwarding local ports offers a neat solution to access applications running on remote servers. However, if you need access to multiple applications from the same remote host (e.g. tensorboard, jupyter lab, jupyter notebook), you will need to allot different ports for each service and forward them accordingly. This becomes quite tedious to use and after a point, is impractical.

What do we do then?

Dynamic Port Forwarding

There’s another type of port forwarding that solves the above problem: dynamic port forwarding. The command to run for dynamic port forwarding is:

ssh -D [bindAddress:]localPort sshServerHost

This looks quite different from the ones above! As you can see, only a port on the local machine is required. It automatically decides the proper destination port based on the network traffic. Dynamic port forwarding thus allows forwarding from not just one port, but a range of ports.

The -D option makes SSH act as a SOCKS5 proxy server. SOCKS5 proxy is basically an SSH tunnel which forwards the network traffic on to the internet. The bindAddress takes on the same role as it did for local port forwarding.

Finally, all you need is a client (your browser) to connect to the SOCKS5 proxy! Check out this post for setting up your browser to follow the SOCKS5 proxy. I give some specifics for Firefox in the section below.

An end-to-end example: Jupyter notebook instance

Local Port Forwarding

- Run a jupyter notebook instance on your remote machine

user@sshServerHost: jupyter notebook --no-browser --port=XXXX

# Replace XXXX with a port number of your choice

# It defaults to 8888 when left unspecified

To access the notebook, copy and paste one of these URLs

http://localhost:XXXX/?token=8be5a53de9220287cb8e61179e7edca0a7b0efa3bcea603b

# copy this URL

- Choose a port on your local machine, say port YYYY, to forward.

- Run the forwarding command on your local machine

user@localMachine: ssh -L YYYY:localhost:XXXX user@sshServerHost

- Access GUI via local browser. Open your browser and type

localhost:YYYYalong with the token or copy-paste the url above, replacing XXXX with YYYY. Viola!

Dynamic Port Forwarding

- Run a jupyter notebook instance on your remote machine

user@sshServerHost: jupyter notebook --no-browser --port=XXXX --ip sshServerHost

# Replace XXXX with a port number of your choice

# It defaults to 8888 when left unspecified

- Run a tensorboard instance on the remote machine

user@sshServerHost: tensorboard --logdir log --port YYYY --host sshServerHost

# It defaults to port 6006

On your local machine, open up your browser and configure its network settings to connect to SOCKS5 proxy with a port number of your choice.

Type

sshServerHost:XXXXandsshServerHost:YYYYeach in a tab and enjoy!

General Tips

Note: Dynamic port forwarding requires the application server’s IP to be set to the SSH Server name. This is easily done through either the

--ipflag or the--hostflag.

You can use the

-Nflag to not open a new ssh window and continue in the same window. The-fflag makes the ssh session go into the background.ssh -N -f -L 8888:localhost:8888 user@sshServerHost

Firefox is ideal for setting up SOCKS5 proxy and dynamic port forwarding. You can set up multiple profiles that bind to different ports and easily switch between them. Just type

about:profilesin your browser tab to get to the interface.

Figure 1: The SSH Protocol

Figure 1: The SSH Protocol Figure 2: A host machine with multiple services running on different ports, constituting differerent sockets, open to connections from clients

Figure 2: A host machine with multiple services running on different ports, constituting differerent sockets, open to connections from clients Figure 3: (left) Example scenario: application server on Host B (Port W) and client on Host A (right) An unsecure direct connection between client and server

Figure 3: (left) Example scenario: application server on Host B (Port W) and client on Host A (right) An unsecure direct connection between client and server Figure 4: SSH port forwarding

Figure 4: SSH port forwarding