WSJ: The Gatekeeper Tests

Saturday, March 24th, 2018The lead article in the Review section of the Wall Street Journal published Saturday/Sunday, March 10-11, 2018 is titled “The Gatekeeper Tests” and written by Nathan Kuncel and Paul Sackett. This article essentially supports the use of SAT and ACT in college admissions. Personally, I believe it is time for a ground-up replacement of these tests and find it no surprise that the credits/disclosure section of this article indicates “In the past they have received research funding from the College Board.” The article is adapted from a publication Kuncel and Sackett authored.

This article is sectioned into myths and research-based arguments why they are misconceived. My read of this article gave me a feeling that the arguments have good intentions (justifying current practice) but lack full perspective. From the use of the words “research” and “facts”, it is clear their perspective is defensive.

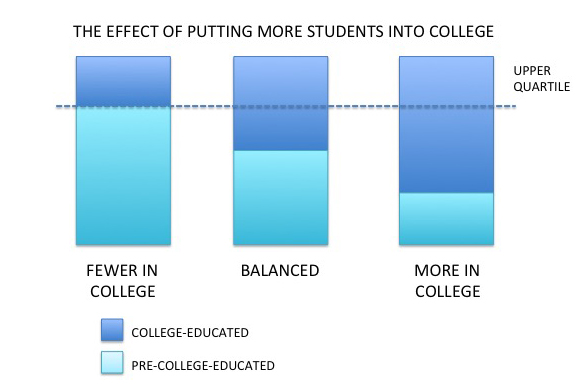

Many of us know that GRADES DON’T MATTER. I would add that SAT/ACT/AP scores mean even less. This ties in well with another WSJ article that I have just commented on titled ” More Companies Teach Workers What Colleges Don’t.” In that comment, I posted a simple graphic that shows the balance of college graduates vs pre-college graduates going into the workforce. The main effect of pushing more students to college creates the greatest economic benefit for test providers (I would have named College Board specifically if I were just focused on US college admissions). Viewed as an exercise in mass action, more college applicants (and more applications thanks to technology) means more test fees. A higher level of competitiveness also results in more repeated testing -> higher fee revenue from each test taker. Just like an argument I saw for supporting the income tax preparation industry, I would believe that the college admission testing industry is on a roll (let’s also include test prep as well as college application counseling services). I am look forward to more colleges making the SAT and ACT optional.

OK, now to my views of the myths.

Myth: Tests Only Predict First-Year Grades. Successful SAT/ACT test takers are largely likely to be successful GRE/GMAT/LSAT/MCAT etc test takers. Test taking is a skill and scales from low to high. Test taking skills can also influence college course grades which rely wholly or heavily on proctored tests (as opposed to take-home finals, papers and presentations). The authors point to evidence that high test scores are predictors of several forms of outstanding achievement; there is no mention of how many high test score students end up with lower college measures and outcomes (remember the effect of students finding themselves average in college because of the selectivity in the admission process). Consider too how students with low Math and Analytical test scores may avoid STEM majors. How too to rationalize foreign students who are able to game the tests by conditioning?; I have read elsewhere about how the college drop-out rate for foreign students is increasing.

Myth: Tests Are Not Related to Success in the Real World. College admission tests measure convergent thinking. They are mostly made up of multiple choice questions – and even when there are other question formats, the key is simply to deduce the right answer (even in the essay). In YCISL, we emphasize the practice of preceding convergent thinking with divergent thinking, and repeating the cycle. Our program also positions real world success as being largely determined by fast thinking (improvisational) skills as well as emotional intelligence which are certainly not what these tests are testing.

Myth: Beyond A Certain Point, Higher Scores Don’t Matter. Higher scores really only matter to one group of people – college admissions staff. And the reason is to cut the workload down in the face of soaring numbers of applications due to the ease of applying thanks to technology and a larger proportion of many countries’ population aiming for college. When I interview students for on-campus jobs, I don’t ask for test scores (they don’t even put it on their resumes). Faculty seeking PhD students for their research groups couldn’t care less. An even when I worked in the tech industry, the interview never touched on test scores. You can’t even use GPAs any more either. So for all practical real world post-college purposes, test scores are buried history.

Myth: Common Alternatives to Tests Are More Useful. It is a pity that the authors discount letters of recommendations, personal statements and interviews in favor of test scores. They seem to miss the modern purpose of the college experience and the importance of self-fulfillment. They are stuck on older indicators of career success such as those mentioned in Ken Robinson’s TEDTalk about time of the Industrial Revolution. One is more likely to find a nugget among those with compelling personal stories (a topic in the YCISL program) than among test scores that measure a specific cohort on a specific date and less so between cohorts. Students would benefit more from self-presentation skills than test scores.

Myth: Tests Are Just Measures of Social Class. This is better phrased as a null hypothesis “Social Class has no influence on test scores” because if you look hard enough, you will likely see pockets of it. But the causation-correlation connection is weak because we also know that students from outside the US social structure have a propensity to ace the SAT tests. This could be due to grit (taken from the title of Angela Lee Duckworth’s TEDTalk) due to the higher barrier that foreign students perceive. Foreign applicants may also have an advantage due to the rigor of their education culture. Even within the US, I would hazard a guess that there are a measurable number of students who aced the SAT without any special prep.

Myth: Test Prep and Coaching Produce Large Score Gains. If we view tests like the SAT and ACT as IQ test derivatives then score gains are unlikely to come from test prep and coaching. But if you put all the factors discussed above together, they are not perfect IQ tests because there is an element of endurance and focus in taking these tests. And how do you build up endurance and help focus? You take practice tests and get someone to shift your viewpoint on test problems you can’t seem to get focus on. Again, these are test taking skills.

Myth: Tests Prevent Diversity in Admissions. Entering college cohorts are becoming diverse despite test scores and not because of them. There is a variety of options open to admissions staff to create the diversity. At my own college, we are quick to mention the presence of scholar athletes. And you may have heard about the legal actions being taken against Harvard. Test scores are a source of frustration.

I would disagree that such standardized test scores are “invaluable” and “effective” – we are just waiting for a revolution – one in which such tests are demoted to where they really belong. It is time to innovate and leverage intrinsic motivation in how we help willing students to pursue their passions for learning and self-development. Let’s get a system which helps you find the right college instead of keeping you in the dark.

There was an online WSJ article today (March, 22, 2018) titled “More Companies Teach Workers What Colleges Don’t” by Douglas Belkin (https://www.wsj.com/articles/more-companies-teach-workers-what-colleges-dont-1521727200) which told about several companies which have training programs for new employees. These training programs don’t seem like anything new and the complaints by employers that colleges are not preparing graduates as perfect fits for their companies reflects usual me-me-me thinking.

There was an online WSJ article today (March, 22, 2018) titled “More Companies Teach Workers What Colleges Don’t” by Douglas Belkin (https://www.wsj.com/articles/more-companies-teach-workers-what-colleges-dont-1521727200) which told about several companies which have training programs for new employees. These training programs don’t seem like anything new and the complaints by employers that colleges are not preparing graduates as perfect fits for their companies reflects usual me-me-me thinking.