MEMORIES OF BEING: ORLAN'S THEATER OF THE SELF

David Moos*

Art + Text 54 (1996), pp. 67-72

The history of art is separate from all history, but connected. It meets everything else, but it has its own constants.

Willem de Kooning, 1958

In his book The Memory of the Body, theater chronicler Jan Kott describes an encounter with the eminent Polish director Jerzy Grotowski. After witnessing Grotowski's troupe of actors being overwhelmed by the exercises, dances, and motions that they were induced to practice and explore, Kott asked Grotowski if he had any documentation of this work. "What for?", Grotowski replied: "The only lasting imprint is made on memory."1 The memory Grotowski has in mind is both the physical memory instilled within the actor's body which enables the performance of a certain role, and the memory of the spectator who experiences the performance. The thread connecting these two specifications of "memory" concerns a definition of what art is. Something is prepared by the artist, in this case within the body, and then it is transmitted, presented to be absorbed into the experience of the viewer.

To discipline the actor's body Grotowski has developed a method for "physical actions" which derive from the central beats of being within the human core. As he explains with regard to "the impulses": "it is as if the physical action, still almost invisible, was already born in the body.... The impulse pushes from inside the body, and we can work on this."2 By training the body with physical actions the actor may train for reality. This learned, stored knowledge will become the actor's source of being when on stage. Such conditioned preparedness of the body is what Grotowski means by "realistic" actions. The affective level of impact demanded by theater is given by the reality of the spectators who maintain the desire "to have something hidden revealed to them, even unconscious hopes that they might see 'something' unknown about themselves." Thomas Richards, Grotowski's essential collaborator, affirms: "It is the actor's duty to reveal to them this 'something,' that which was left either unobserved or forgotten."3 That Grotowski's theater may unlock or dislodge something essential in the spectator's being concerns orders of reality shared between actor and spectator, artist and viewer.

The reality ignited by art will be less something shared in common by spectator and artist than a given consciousness that becomes a site of subjectivation onto which memory may form itself. When the twin faces of reality, of artist and viewer, stand before each other, the artifice that art consciously constructs becomes the reality in which both beings participate.

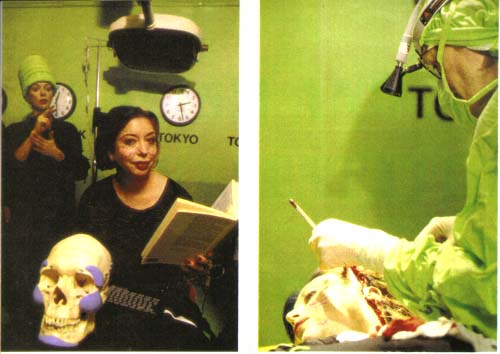

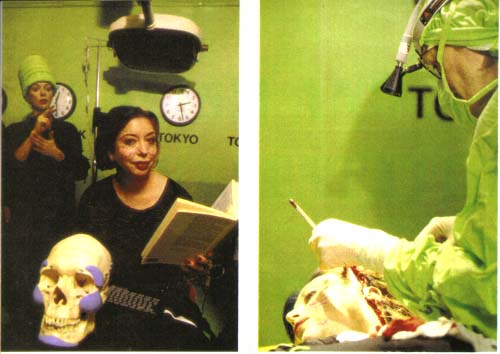

SCENES FROM THE OPERATING ROOM DURING ORLAN'S 7TH PLASTIC SURGICAL OPERATION ENTITLED NEW YORK OMNIPRESENCE. NOVEMBER 21, 1993, PROCEDURE INVOLVED SEWING IMPLANTS INTO ORLAN'S TEMPLES TO CREATE TWO LUMPS, AND PLACEMENT OF AN IMPLANT INTO HER CHIN THROUGH THE LIFTING OF FLESH AND INSERTION OF MUSCLE TISSUE.

PHOTO

SICHOV COURTESY THE ARTIST

PHOTO

SICHOV COURTESY THE ARTIST

Consider the theater of Orlan. It aims to impact memory, to physically condition this mental state, thereby suggesting that one's thoughts and the recollection upon which they rely can somehow be tangibly modeled, shaped. In its deliberate diversity Orlan's art constructs memory through a plurality of media that will ensure that "something"--whether a face (hers), a feeling (yours), a desire (of artist and spectator)--be both transmitted and received. Text plays an active role in this process and is submitted to as wide a range of articulations as are images, Orlan's self- produced self- imagery.

The central text that Orlan has "put into action," in the manner of a script being rehearsed and performed, is taken from the Lacanian psychoanalyst Eugenie Lemoine Luccioni. The passage relates a founding schism between external and internal appearances, the way one appears to the world versus one's own self- perception:

Skin is deceiving--in life, one only has one's skin--there is a bad exchange in human relations because one never is what one has. I have the skin of an angel but I am a jackal ... the skin of a crocodile but I am a poodle, the skin of a black person but I am white, the skin of a woman but I am a man; I never have the skin of what I am. There is no exception to the rule because I am never what I have. 4

The literality of Orlan's interpretation--and implementation--of this passage is provocative for it imbues text with an affective potential, reifying it through surgical performance, as predicate upon which the body is modeled.

Merleau- Ponty's quest in phenomenology culminated in the insight that consciousness and world alight transparently together in the flesh of the body. To achieve a verifiable reality for thought and to attain "true vision" for the self's existence in the world, Merleau- Ponty sought to lay thought onto the body and in this proximity to have their meeting become indistinguishably entwined: interface as sheer surface, the flesh. Merleau- Ponty used paired terms, "The Intertwining-- The Chiasm," to designate this condition: "The body proper embraces a philosophy of flesh as the visibility of the invisible."5 Here sight would acquire a tangibility for thought, a merger that produces a physicality for being.

The project proposed by Orlan enacts a text of being which is laid onto/into her body, as intentional thought. The skin thus becomes "the intertwining" of sight's physicality onto the being of her body. In a small so- called "reliquary" this configuration is depicted. Illuminated by light reflecting off the white wall behind, Orlan's post- operational visage has been transferred onto a swath of gauze. The coagulate surface of the gauze is a former part of the skin, for like her skin it served the function of retaining the blood flow within the body. The gauze, like the skin of the face, is Orlan's metaphor for the thin, osmotic surface of being, its existence as interface, intercourse between inside (flow) and outside (appearances).

What are the limits of this intertwining, and where lie the boundaries separating what we are able to distinguish as internal/external, visible/invisible, self/-------? With the self antithesis may be occupied by non- self, other, world, each of which designates an improper counter- option. It is this polarity, necessarily incomplete, that becomes the core of Orlan's project. Her skin becomes the blank in this equation, the mediating material with which she articulates, in the manner of author, painter, artist, her central problematic. For the moment, the open- ended proposition of "self/-------" may be completed with the word "portrait."

Orlan's art is essentially produced through staged performances that take place (theatrically, dramatically) within the hospital's operating room, her "studio." Certainly all of the writing, from sensational reports in the popular press and fashion magazines to sustained critical appraisals, focus on this prime venue Orlan has been working in since 1990, when she undertook her first surgical alteration. Each essay--from Details magazine's report on plastic surgery,6 to post- human, techno- science renditions of Orlan's body,7 to the strong feminist and psychoanalytic readings of her project8--scarcely engages the work from an art- historical perspective. The subject of self- portraiture, developed from within art history (Orlan's avowed point of origination), has yet to receive critical or scholarly attention. Investigating self portraiture as a genre would of course posit Orlan within an art- oriented sphere of operations different from apparent performance and body art peers such as Chris Burden, Bruce Nauman, and Herman Nitsch (to cite the context proposed by Barbara Rose).9 Unlike these artists, who perform and document frequently painful expressive actions, Orlan is immersed in a self- portrait that must move through physical states of becoming. In this manner, if one reads art back onto the self--as indeed self- portraiture has always implied--the example of painting becomes vitally instructive.

If the genre initially proposed the fiction of an autonomous likeness of the artist, by the seventeenth century self- portraiture had evolved complex narrative mechanisms within which the artist could present himself. With Velazquez's Las Meninas the task of self- depiction is problematized through the artist's implicating of the observer, whom he has conflated with figures reflected in a mirror. As Foucault wrote of the painting's visual matrix: "there occurs an exact superimposition of the model's gaze as it is being painted, of the spectator's as he contemplates the painting, and of the painter's as he is composing his picture [the self- portrait]."10

Velazquez supplies us the cue to painting's reflexivity and reversibility by depicting himself at work on a large canvas, the back of which we see along the left edge of Las Meninas. The subject of this painting shown within the painting remains hidden. All we see is the underside, the backside of the skin of the painting the artist shows himself to be working on. Of course, it is ourselves whom he labors to render onto this canvas as we watch him looking at us. By showing us the back of a painting in progress within his composition, Velazquez depicts what lies behind the surface of painting--a trope Orlan has exploited to the fullest. Her creative plane is her skin, a surface that is drawn upon, stretched over a skeletal frame, incised with the scalpel.

In addition to the videotapes, photographs, and reliquaries resulting from the operations, a significant portion of Orlan's work is presented in gallery spaces, on the white walls created by modernism's belief in painting. Installed, for example, in the Centre Pompidou in 1994, following her seventh operation, were 41 consecutive diptych self- portraits. This series of self- imaging proceeds temporally. Along the top register are photographs of the artist's face taken on the day surgery was performed, and then each subsequent day until full convalescence had occurred and the rigors of medical intervention receded. The lower register of the diptych is comprised of computer- generated portraits of Orlan as composites of ideal female portraits. With morphing software Orlan superimposed upon her own facial image the chin of Botticelli's Venus, the eyes of Gerome's Psyche, the forehead of Leonardo's Mona Lisa, the mouth of Boucher's Europa, and the nose of a School of Fontainebleau Diana. "After mixing my own image with these images," Orlan notes, "I reworked the whole as any painter does, until the final portrait emerged and it was possible to stop and sign it."

Variance within this modulated configuration is allegorically as great as the disparity shown along the upper register: between the tumescent, medically altered post- operational face, and the composed visage presented at the conclusion of the sequential self- portrait. For Orlan the body's healing process continues the portrait work instigated surgically. Over a 41-day span the face is seen to change color, the blue bruises fade to yellow, bloated areas settle into smooth contour. The installed self- portrait succinctly establishes, in Orlan's words, "a comparison between the self portrait made by the computing machine and the self portrait made by the body- machine."

In reference to such a trajectory, the phrasing of philosopher Gilles Deleuze and psychoanalyst Felix Guattari is directly relevant for an understanding of how the rigors of facial rendering relate to the body proper. "It is precisely because the face depends on an abstract machine that it is not content to cover the head, but touches all other parts of the body, and even, if necessary, other objects without resemblance." The face may take into itself its surroundings and other objects and, most importantly, painting may "position a landscape as a face, treating one like the other."11 Orlan's project intends these extended territories and encodes them into its procedure: if the use of satellite links extends and transmits her face across space (as with her seventh operation in 1994, during which the operating theater was linked in real time with participating audiences in Tokyo, New York, Paris, and so on), conceptually the reference to landscape becomes central. The prolonged horizontality of the self- portrait, of reiterated faciality, has situated, absorbed, and merged into itself narrative properties of the body as corporeal landscape.

"Flesh was the reason why oil painting was invented," Willem de Kooning wrote in 1950,12 the year he began work on Woman I, a painting which over a two- year span was completed and then painted out literally hundreds of times. "Because de Kooning wanted to put everything into his painting," Thomas Hess noted, "each thing he got into it not only had its own presence, but represented the absence of something else."13 Indeed, in photographs taken throughout the evolution of Woman I a window clearly appears at the top right corner of the composition, present in some versions, absent in others--obliterated in the final painting, the ultimate window onto the body.14

Cardinal to de Kooning's working method has always been the interim image, a priority separating him from his Abstract Expressionist colleagues and which he maintained throughout the 1980s when his work, preoccupied with the sheer surface of paint, embraced a more fluid concept of flesh. The late work depicts de Kooning's final reckoning with the body--the human body conceived as a skin within which the artist, his model and the world (explicitly landscape) may abut, abrade, and coexist. A glance at sequential stages in the development of Untitled XXIII (1982), revealed through photographs which were taken as part of de Kooning's working method, suggests that interim states be regarded as somehow crucial to the final work--that underneath the surface of the image paint's body could maintain a memory of how it was, a form previously assumed. De Kooning's paint brings forth glimpses of content: the close- up of a figure; a turgid stretch of landscape; incisions that create a rupture of red; the flesh recumbent, organized by dangling limbs. The anatomy of the painting quickly becomes its physiognomy, where in the ever- evolving circuit of surface the painter comes to see himself reflected from the inside on the surface of the painting.

De Kooning's art has always been a corporeal struggle to resolve the body's inside with the externality of the world. In the late works' collapsing of depth, where strokes rush through the surface, blur within the white/flesh to section shape into form, the complex merger of self perceiving subject/world/self in paint is transacted in its most declarative, simplified terms.15 Here one may index Orlan's method as similarly engaged in a reckoning with how process gives rise to form, and finally to (self- )formulation. Her process videos and the resultant still photography from the operations are akin to glimpses into the transitive formation of a de Kooning painting, where stages of becoming determine the next action within the stream of impulse.

In the intense time of surgery, which is akin to the time of making (painting and performance), the images flow at an almost ungraspable clip, a flood impossible to absorb. As in the painter's mind, balancing not the look hut the being of self/model/world, Orlan's work rapidly moves through states of making which are instantly covered over, closed up, and passed through--in the manner of de Kooning's brush passing over or lining off parts of the painting. The surgeon's drawing upon her face is quickly replaced by incisions, which yield lines of blood, open folds in the flesh, create shapes, even forms which exist for moments when the face is detached--disembodied to be reformulated. It is this process, the decision- making essence of her art in action, that is most intimately linked to painting: to, for instance, de Kooning's style. The visible dissolving into the invisible, where what is no longer seen becomes the preserve of memory, constructs the fleeting after- image associated with consciousness.

Within this stream of action the self is maximally opened to a horizon where perception, experience, and the external world all come to exist along the plane of the body. At this juncture, perhaps a suture, flesh and idea are merged, intertwined in what Merleau- Ponty phrased as:

... a new type of being, a being by porosity, pregnancy, or generality, and he before whom the horizon opens is caught up, included within it. His body and the distances participate in one same corporeity or visibility in general, which reigns between them and it, and even beyond the horizon, beneath his skin, unto the depths of being. 16

The consciousness provided by this state of being, which is received in the body, is performed by Orlan when she is directing her surgical interventions. Impact beyond attainment of a moment--as process of making--where world and self exist as the flesh together, shall become the space of memory, the formation of memory as unforgettable experience. Orlan cites a favorite phrase of hers: "Remember the Future." She challenges memory to recall how her face and body previously appeared, asking what being lies beneath/within her self- depiction.

Within this performative evolution memory is always held in suspense, stored in some unique place, perhaps in the manner de Kooning sees the history of art as "separate from all history, but connected." How such memory attaches to states of being will be in the phenomenal sphere of art where perception connects to the physical body--a new type of being that is opened as a horizon to include all distance, both without and within. Such a recognition describes the aim of theater which Grotowski poses like the intervention of Thomas who must overcome doubt by touching the essence of the intangible: "These investigations will be like a finger stuck in the wound of the spectator, who will see himself reflected in the mirror of the actor's actions."17

DAVID MOOS is a curator and art historian based in New York. He is the editor of "Painting in the Age of Artificial Intelligence," a special issue of Art & Design, and Visiting Professor at the University of Guelph, Canada.

NOTES

1. Jan Kott, "Grotowski, or the Limit," The Memory of the Body (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1992), 67.

2. Jerzy Grotowski, conference at Liège, 1986; quoted in Thomas Richards, At Work with Grotowski on Physical Actions (London: Routledge, 1995), 94- 5.

3. Richards, ibid., 102.

4. This, and subsequent quotations of the artist are from "Intervention--Orlan" (1994); artist's manuscript translated by Tanya Augsburg and Michel A. Moos. For another translation of this manuscript, see "I Do Not Want to Look Like ...", Women's Art 64 (May- June 1995), 5- 10.

5. Maurice Merleau- Ponty, "Nature and Logos: The Human Body," In Praise of Philosophy and Other Essays (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1970), 197.

6. Pat Blashill, "The New Flesh," Details (August 1995),46- 54.

7. See Dr. Rachel Armstrong. "Post- Human Evolution," Artifice 2 (1995), 53- 63. For a postmodern defining of Orlan's project, see Philip Auslander, "Orlan's Theater of Operations." Theater Forum 7 (Summer- Fall 1995), 25~31.

8. See Parveen Adams, "Operation Orlan," The Emptiness of the Flesh: Psychoanalysis and Sexual Difference (London: Routledge, 1996), 141- 159; Tanya Augsburg, "Beyond Hysteria: On Orlan's Transformations of Subjectivity," unpublished manuscript, 1995.

9. Barbara Rose, "Is It Art? Orlan and the Transgressive Act," Art in America 81:2 (February 1993), 82ff. For a thoughtful overview of Orlan's surgical projects and their relation to art. see Carey Lovelace, "Orlan: Offensive Acts," Performing Arts Journal 49 (1995), 13- 25.

10. Michel Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Random House, 1970), 14- 15.

11. Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia, trans. Brian Massumi (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1987), 170, 172.

12. Willem de Kooning, "The Renaissance and Order," Trans/formation 1:2 (1951).

13. Thomas B. Hess, Willem de Kooning (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1968), 22- 23.

14. Six stages of Woman I are reproduced in Willem de Kooning, exhibition catalogue (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, l 983), 176.

15. These remarks are enormously compressed observations about de Kooning's method. For prolonged analysis of his studio method throughout the 1980s. see Robert Storr, "At Last Light," in Willem de Kooning:The Late Work, The 1980 Exhibition Catalogue (San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. 1995), 39- 79.

16. Maurice Merleau- Ponty, The Visible and the Invisible (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 1968), 149. Merleau-Ponty surmises a primordiality of vision that inhabits both the seer and the seen, an "anonymous visibility: where inside and outside turn around one another. Such a collapsing of the Cartesian dichotomy between self and world is phrased as follows: Where in the body are we to put the seer, since evidently there is in the body only `shadows stuffed with organs,' that is, more of the visible? The world is not `in' my body, and my body is ultimately not `in' the visible world: as flesh applied to flesh, the world neither surrounds it nor is surrounded by it." (p. 138). For commentary on these issues, see James Schmidt, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Between Phenomenology and Structuralism (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1985), 598.

17. Thomas Richards, op. cit. 103.