Preliminary -- Do Not Quote or Cite

T-Shares: A New Way for Investors to Share Investment Outcomes

William F. Sharpe

January, 2002

Introduction

A society makes investments. Those investments produce future outcomes and investors share those outcomes. But investors differ in their positions, preferences and the probabilities that they assess for alternative future investment outcomes. A key function of the financial services industry is to help investors efficiently share investment outcomes, taking each investor's characteristics into account. To do this, the industry has created a great many institutions and financial instruments.

Recent decades have seen a great increase in the use of derivatives. Broadly, a derivative security's value depends on the value of some other security or portfolio of securities. Unfortunately, some of these instruments are expensive, opaque, and subject to real or perceived counterparty risk.

This paper proposes a new type of derivative, called a "t-share", that can be inexpensive, transparent and have no counterparty risk. The use of such shares could supplement and/or replace a number of existing institutions and instruments. T-shares use principles that underlie existing financial products but combine them in new and somewhat different ways.

Legal, regulatory, and taxation problems may defer, limit or entirely preclude the use of t-shares, at least in some countries. However, even if this is the case, there is still merit in understanding their characteristics, since they provide simple analogues that can help investors better understand and evaluate existing institutions and instruments.

Characteristics of T-Shares

A series of t-shares is initiated when an individual or institution (the "creator") deposits a set of assets with an institution we will term the "trustee". The trustee is a respected organization of impeccable reputation, such as a large international bank or experienced mutual fund company. The creator and the trustee agree on a set of rules for managing the assets, generally in a highly passive manner, and a set of rules for distributing the assets to holders of shares in two or more "tranches", which constitute the liabilities and net worth of the trust. The tranches are paid in strict priority order, with all payments to tranche 1 completed before any payments are made to trance 2, and so on. Each tranche is paid amounts based on the pre-specified formula or the remaining assets, whichever is smaller. The final tranche receives any remaining assets after all prior tranches have been paid. The trustee is paid a fee out of assets at a rate determined when the trust is initiated.

At the time of the trust's creation, the trustee issues a pre-specified number of shares in each tranche to the creator. Shares are registered in book form by the trustee, who maintains the register of owners and makes payments directly to them.

At any time the creator of the trust can sell shares in the tranches to anyone. Investors who have purchased shares are free to sell them to other investors as well. While a separate institution could be set up to facilitate such transactions, it is entirely possible that an existing market such as EBay could be utilized. Shares could be offered in auctions (perhaps with reserved minimum prices) or for fixed prices, as the sellers desire. Buyers could also bid for shares.

In most cases, the rules governing payments made to the tranches would use a "payoff formula" based on the value of an "underlying variable". Typically the variable would equal the value of all or part of the underlying assets, but this need not be the case.

Each security issued by the trustee is given a designation that includes the trust number, the tranche number, and the total number of tranches in the trust. Thus 123-2/5 would refer to a share in trust number 123, tranche 2 of 5.

The term "t-shares" is used since the procedure involves the use of a trustee, a trust fund, and tranches of securities.

We illustrate with three examples.

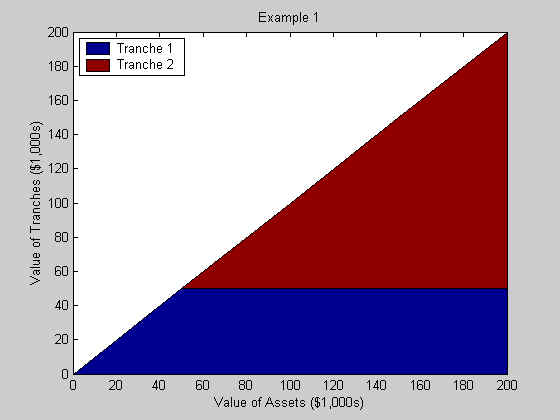

Example 1: Levered Investment in the Stock Market

In the first example, an individual deposits $100,000 worth of securities representing a diversified portfolio of U.S. equities (for example, shares in the Vanguard Total Stock Market Fund or the Vanguard VIPER exchange-traded fund). Until December 2005, any cash flows received by the trust are to be reinvested in the same security. Tranche 1 consists of 5,000 shares, each of which is to be paid either $10 or 1/5,000'th of the assets, whichever is smaller, in December 2005. Tranche 2 consists of 5,000 shares, each of which is to be paid 1/5,000th of the assets that remain after the payments are made to tranche 1 shares. The underlying variable in this case equals the value of the assets in the fund in December 2005. The figure below plots the total values of the tranches (on the vertical) axis, as a function of the value of the portfolio (on the horizontal axis).

Tranche 1 securities can be thought of as risky zero-coupon bonds with a promised payment of $10 at maturity. Tranche 2 can be considered a levered investment in the U.S. equity market. An investor wishing to in effect borrow on margin to invest in the U.S. equity market could create the two tranches, keeping all of the shares in tranche 2 and selling those in tranche 1 at auction. His or her net cost would then equal $100,000 minus the proceeds from the sale of the tranche 1 securities. The amount paid by the buyers of tranche 1 would depend on their assessment of the likelihood that the equity market would fall more than 50% by the end of 2005 and the disutility associated with losses in such circumstances.

Note that the payoffs depend only on the final value of the underlying assets so there is full transparency. The loan is fully collateralized and the holder of shares in Tranche 2 has no added liability in any outcome. The trust simply allows the investors to share the investment outcomes provided by the trust assets.

A trust of this type could allow the creator could obtain a security with payoffs that might not be available otherwise (or, if available, might be more expensive). In other cases the creator might plan to sell all the securities in the trust series in the hope that the sum of the proceeds would exceed the cost of the assets deposited when the trust was set up. This could be the case if the series shares helped other investors obtain desirable payoffs not available elsewhere. Of course once it became clear that there was significant demand for such sharing arrangements, others would offer new trusts with the same structure until the demand had been satisfied and the sum of the prices for the series no longer exceeded the value of the underlying assets.

In some cases the value of all the shares in a trust series might fall below the current value of its assets. This could be obviated by providing for the redemption of proportionate combinations of shares with assets at any time, or the discrepancy could be allowed to persist, as is often the case with traditional closed-end funds. In any event, trusts in such circumstances would not likely be copied by others.

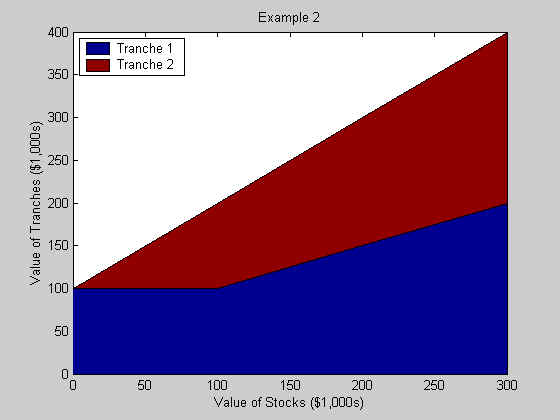

Example 2: Downside Protection and Upside Potential

Our second example provides an analogue to retail financial products that offer investors the "downside protection" of the bond market and some of the "upside potential" of the stock market. The trust assets include (1) five-year zero coupon treasury bonds with a maturity value of $100,000 and a current value of $75,000 and (2) securities representing the U.S. stock market with a current value of $100,000. Any income provided by the assets is reinvested until a date five years hence. At that time, tranche 1 is paid the lesser of (1) the current value of the assets or (2) $100,000 plus half the increase (if any) in the value of the stocks. After tranche 1 is paid, the holders of securities in tranche 2 receive their proportionate share of the remaining assets.

The payoff diagram in this case is shown below, using the value of the stock portfolio as the underlying variable.

Note that, as intended, tranche 1 provides shareholders with the downside protection of a fixed minimum value and the upside potential of a partial share in any stock market gains. Holders of securities from tranche 2 receive upside potential as well, but suffer considerable losses in the event that the stock market closes at a lower value than at the outset.

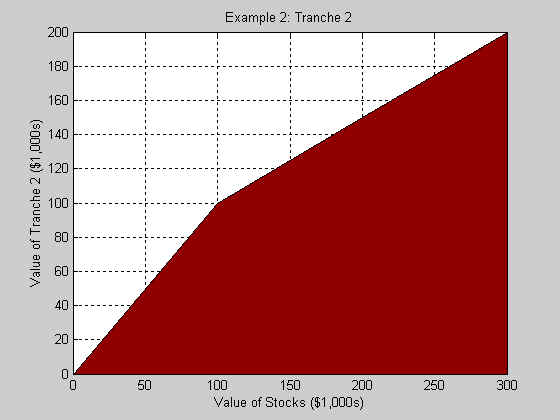

The value of the tranche 1 securities will depend on investors' assessments of the probabilities of various final stock values as well as the utility associated with wealth in each of the possible outcomes. We would expect the securities to sell for more than $75,000 since they provide the same floor as a zero-coupon bond and some upside potential. Consider, for example, a case in which the securities in tranche 1 happened to sell for $100,000. In this instance, the securities promise holders that they will receive all their investment back in any outcome, and more in outcomes in which the stock market closes higher in five years. They have, in effect, purchased insurance against loss. Clearly, the holders of tranche 2 securities have provided that insurance. Their reward is the opportunity for high returns if the market goes up sufficiently. In this example, they could pay $75,000 for their securities. The figure below shows the final payoff for tranche 2 as a function of the final value of the stocks in this case.

If the market is unchanged, tranche 2 investors receive $100,000 for their investment of $75,000 --a 33% return over the five years. If the market rises, they receive half the additional dollar gains. If it falls, they lose a dollar for each dollar decline. The break-even point comes at $75,000, so that tranche 2 investors gain as long as the market does not drop by 25% or more in five years.

When asked, most investors will say that they would like downside protection and upside potential. However, for some investors to have this, others must "take the other side". There is some price at which the number of those wishing to have such payoffs will equal the number willing to provide them. The use of t-shares for this purpose makes this very clear. Ultimately the prices of the two tranches will settle to levels at which the demand for the two types of shares equals their supplies.

It is useful to contrast the simplicity of tranche 1 in this example with the complexity of a typical retail "protected investment product". The fine print for such an instrument typically discloses that payments will be made by an organization that is related to the selling agent, with caveats for exceptions that may arise in the event of defaults by some other (sometimes unnamed) counterparty. In many cases the vendor uses the proceeds to buy a set of zero-coupon bonds and an over-the-counter call option on the underlying stock index. The writer of the call option may actually hold a stock portfolio or may plan to make any required payments out of other assets, which may be collateral for many other contingent claims. While the organizations may have been given credit ratings by an outside agency, such ratings may fail to take all the relevant information into account, and may in any event change during the life of the contract. In some cases one or more of the parties in the chain of agreements plan to use dynamic strategies to hedge their obligations. This can be dangerous since the assumptions about market movements utilized in selecting the strategy may not be valid in some future contingencies. All these issues give rise to credit and/or counterparty risk, so the original investor's payoff diagram is, at best, somewhat fuzzy, reflecting uncertainty due to factors other than the value of the underlying variable. None of these problems arises with the t-share version. The buyer of shares in tranche 1 knows precisely what will be received, conditional on the final value of the stock portfolio. There is full transparency. Moreover, there are identifiable sellers of the protection (the holders of tranche 2 securities).

A drawback of this type of arrangement is the lack of the ability of a single institution to pool risks by issuing a set of claims, each on a different asset, taking advantage of less-than-perfect correlation of the asset values. On the other hand, as experience has shown, there may be unusual circumstances in which assets may be far more highly correlated than initially assumed, causing significant problems for counterparties. In any event each t-share is fully collateralized. This provides holders guaranteed payments in accordance with the terms of the trust, but at a potential cost. For this reason, t-shares are best written on pools of assets that are themselves well-diversified, such as index funds or equivalent ETFs.

Example 3: A Collared Security

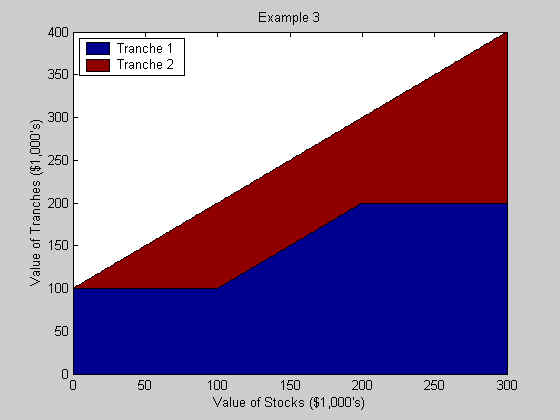

The next example shows how a collared investment can be created, and illustrates the payoff structure that must be accepted by other investors in order to provide a collared payoff.

As in example 2, the trust assets include (1) five-year zero coupon treasury bonds with a maturity value of $100,000 and a current value of $75,000 and (2) securities representing the U.S. stock market with a current value of $100,000. Any income provided by the assets is reinvested until a date five years hence. At that time, tranche 1 is paid (1) $100,000 if the current value of the stocks is less than $100,000 (2) the current value of the portfolio less $100,000 if the stocks are worth between $100,000 and $200,000, and (3) $200,000 if the stocks are worth more than $200,000. After tranche 1 is paid, the holders of securities in tranche 2 receive their proportionate share of the remaining assets.

The figure shows the overall payoffs. Note that the payoff structure for tranche 1 is that of a collared investment (sometimes called an "Egyptian" due to its similarity to ancient figures from that country).

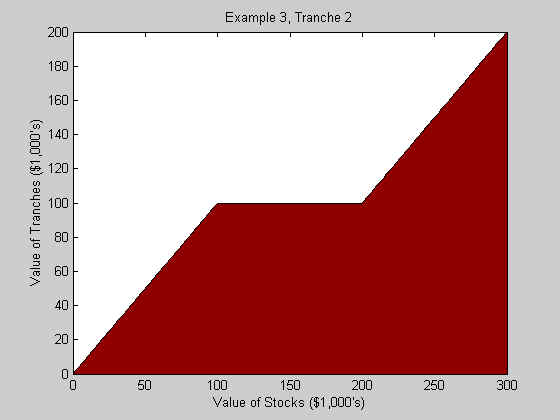

The figure below shows the payoffs for tranche 2. This shape is sometimes termed a "Travolta" due to the similarity to the pose struck by the actor in one of his classic films.

Example 4: Range Securities

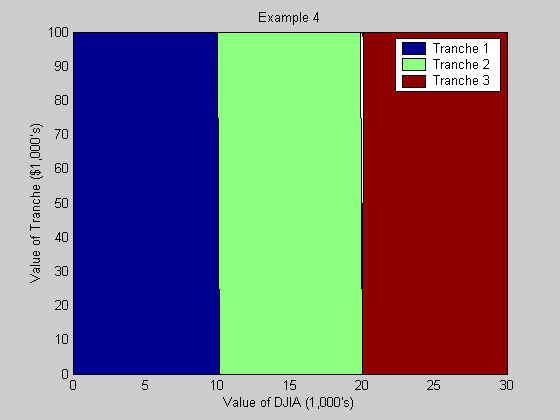

We conclude with one final example to show the potential of the t-share approach.

In this case the assets in the trust are zero-coupon five-year bonds. There are 3 tranches. Payoffs are based on the value of a the Dow Jones Industrial Average in five years. Tranche 1 holders receive all the assets in five years if the index is at or below 10,000. Tranche 2 holders receive all the assets in five years if the index is between 10,000 and 20,000. Tranche 3 holders receive all the assets if the index is greater than 20,000.

As many range securities of this type as might be desired could be created. Given enough of them with narrow enough ranges, an investor could create a steo-wise approximation to any desired payoff diagram on which the horizontal axis plotted the value of the underlying stock index and the vertical axis the amount to be received by the holder of the portfolio. An alternative structure could hold securities from the underlying portfolio, creating tranche payoffs each of which would vary within its specified range.

Conclusion

Our four examples only hint at the range of possibilities that the t-share structure would make possible. A great deal of experimentation would be needed to find combinations that could truly provide investors with better ways to share investment outcomes. In any event, the ability to create, buy and sell t-shares would allow a great deal of flexibility for investors wishing to have shares of outcomes that differ from those available with currently-existing securities and portfolios. To the extent that there is sufficient demand for such arrangements, individuals and institutions could provide new products and be rewarded for doing so. To be sure, there would be significant challenges with regard to regulation and taxation, and costs would have to be kept low. Despite these caveats, it would seem that the time may have come to take advantage of the economies of scale and scope derived from modern computational and communication power to introduce new investment vehicles of this type to help investors share investment outcomes.