|

|

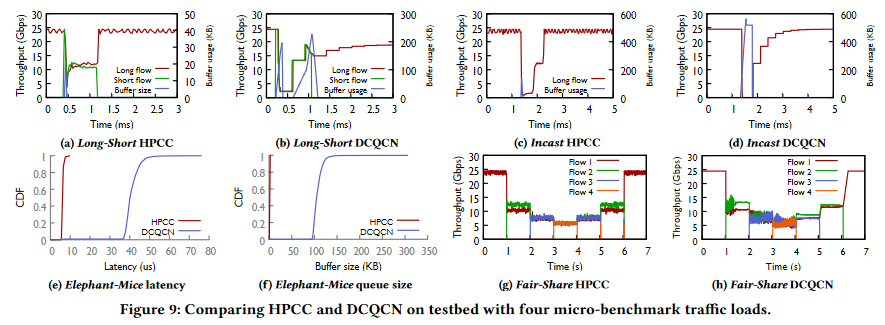

Eliminate Page Limits for Final Paper VersionsMost conferences today impose page limits on papers, both for the submitted versions and for the final "camera ready" versions. This document argues that page limits for the final versions serve no useful purpose and in some cases they harm the quality of papers. These limits should be abolished, leaving it up to shepherds and authors to decide on the best length for each paper. The history of page limitsIn the ancient past (the 1980's), conferences had no page limits for submissions; there were often guidelines or requests, but they were rarely enforced. Conferences did have page limits for final versions, in order to control the cost of printed conference proceedings. Authors were given the option of paying for extra pages to cover printing costs; there was usually no limit on how many additional papers authors could purchase. At some point conferences began to enforce page limits on submissions. By 2008 all of SOSP, OSDI, NSDI, SIGCOMM and USENIX ATC enforced page limits of 14 pages (including references). Over the next few years, all of those page limits were reduced. By 2015 ATC's limit had shrunk to 11 pages (not including references) and the others had shrunk to 12 pages (not including references). The primary reason for reducing page limits on submissions was to reduce the reading load for program committees. This motivation does not apply to the final versions of papers, yet the page limits for final versions shrunk along with those for submit versions (typically one more page than the submission limit). This happened even though the motivation for page limits on final versions (printing costs) has gone away with the advent of all-electronic proceeedings. Furthermore, the option to purchase additional pages disappeared. Today, most program chairs have leeway to grant exceptions to the page limits for final versions, but attitudes on this vary: some are liberal while others enforce the page limits strictly. Problems with page limitsThe problem with page limits is that in many cases they damage the quality of papers. There is no one-size-fits-all for papers: some require more space to describe thoroughly than others. My experience is that it is extremely difficult to motivate, describe, and evaluate a complex system thoroughly in 12 pages. A big and bold new system that challenges traditional thinking takes considerably more space to describe than an incremental improvement. Conforming to page limits forces authors to choose between one of two evils. One choice is to omit entire topics, such as certain aspects of the design or some evaluation experiments. The other choice is to make descriptions more superficial. Either of these choices makes a paper worse. Evidence of this damage is easily visible today. One manifestation is that reviewers often complain about missing material in a paper, when the only reason the material was omitted was to get under the page limit. As an author, it is very frustrating to see criticism like this, and we often wonder if a paper was rejected only because the page limit prevented us from describing the system properly. Another problem is "nano-graphs", a phenomenon where authors shrink graphs to tiny proportions in order to save space. These graphs are not only hard to read, but they lose important information. Here is an example from a recent paper:

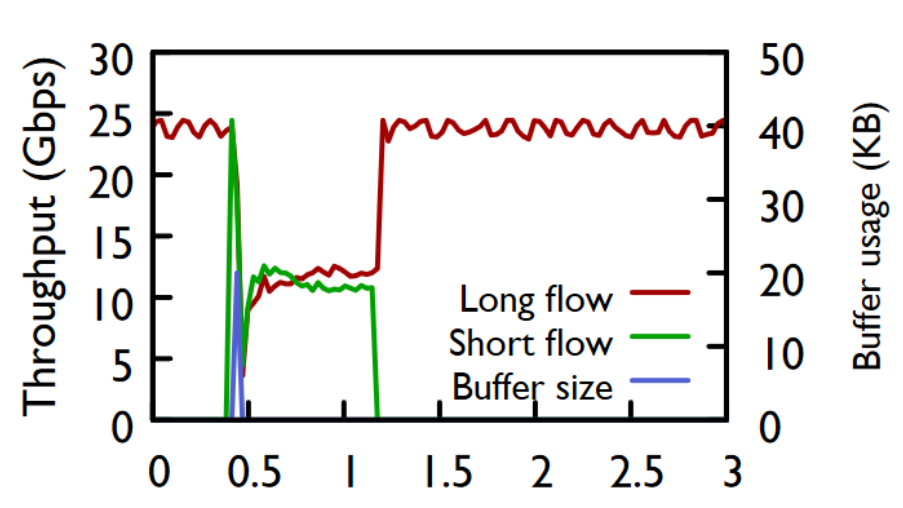

The most interesting part of the upper-left graph is the inflection point around x=0.5ms, but the graph is so small that it is impossible to see what is happening there. One option is to use an online reader to magnify the view, but this doesn't help:

The problem is that small graphs often don't contain enough information for magnification to help. If these graphs had been larger from the beginning, the authors would probably have raised the level of detail as well. Example: the Raft paperMy goal is to publish the best possible papers, and I like to build large and sophisticated systems. This means that I often end up begging PC chairs for extra pages for the final version. Sometimes they agree, but often they deny. They do this even though everyone involved agrees that the longer paper is better. The most common excuse is that allowing more pages for one paper would be "unfair to other authors" (as if the right to produce a high-quality paper is a scarce resource that must be rationed among authors). As an author, having to beg for the right to publish the best possible paper is frustrating, and being forced to publish an inferior one is even worse. As one example, consider the Raft paper, which appeared in USENIX ATC in 2014. This paper required an unusually large number of pages (more than 16), but the official conference limit for final versions was 12 pages. After much arguing, the PC chairs eventually granted us 14 pages. Given this limit, we decided to omit entire sections on client interactions, linearizability, and log compaction; all of these are important parts of the Raft protocol! We ended up publishing an "extended version" of the paper separately, which included all of the missing information. Over time, the extended version has become the authoritative version of the paper; it is the one most commonly read and cited. This benefits no one. It is awkward for readers, because they have to deal with two different versions, and it is undesirable for ATC because ATC no longer serves as the authoritative source for this paper. I hope someday to convince USENIX to replace the published version with the extended one. Proposal1. Because of the challenges in recruiting program committee members, I do not propose changing the page limits for submitted papers. 2. There should be no hard limits on the lengths of final versions of papers. It should be up to shepherds and authors to work together to produce the best possible papers. Authors should be encouraged to use more pages if this makes papers more readable and informative, for example by restoring white space squeezed out for the submission or by making graphs larger. 3. Submit versions of papers should be allowed any number of pages of optional appendices. Committee members are not required to read this material during the review process, but the appendices allow authors to declare additional material they would like to add back to the paper for the final version. Program committee members can check the appendices before complaining about missing material. Potential concernsHere are several concerns that have been raised about this proposal, along with my responses. Page limits force authors to be concise. I started reviewing papers long before page limits were enforced, and I have not seen any evidence that page limits have improved the quality of papers. Journal papers do not have any page limits, but they do not appear more wordy to me than conference papers; they are just more complete. Furthermore, the page limits for submitted papers will continue to force authors to choose their words carefully. It seems unlikely that authors will go back after a paper has been accepted and intentionally make it wordy. If this happens, shepherds can act as a brake on such behavior. Papers will become bloated with unnecessary material. There is no incentive for authors to add material that no one wants to read. And, any new material must be approved by the shepherd. A fixed limit is fair to everyone; it's unfair for some papers to get more pages just because their authors complain. A uniform limit isn't actually fair, in the same way that buying only XL T-shirts for attendees of a conference isn't fair. Some papers need more space than others, and a fixed limit discriminates against them. It's better for shepherds and authors to decide together the length that results in the best possible paper. The new material will not have been properly reviewed. This is a reason for allowing unlimited appendices in submissions, so that program committees can check out this material if they wish. Even if they don't, shepherds can review new material and get feedback from other program committee members if needed. Authors can publish an extended version elsewhere to supplemental a shorter conference version. This can be done, and I have done it on multiple occasions, but it doesn't make sense to me: why not have a single authoritative version, published in the conference proceedings? Rather than creating new rules, it's better to leave this informal, letting individual PC chairs decide what to do. Unfortunately this approach doesn't seem to be working. I end up repeating the same arguments over and over again to every program chair. By the end of the discussion they are usually convinced that more leeway would be better. However, this always happens late in the process; they are afraid to make last-minute changes, and they often get stuck on the fairness issue. Every conference has a different set of program chairs and there is no institutional memory, so the process repeats over and over. ConclusionsOur conferences should focus on publishing the best possible papers. Hard page limits on final versions of papers work against this goal, and they penalize work that is bigger, deeper, and more comprehensive. Thus, the limits should be eliminated. I don't think that eliminating the limits will affect very many papers. In many cases, the ideal length will be not much more than the conference submission length. However, for some papers it will make a big difference. One final reason for allowing longer camera-ready versions is that we have largely done away with journal publications in computer systems. In the distant past, authors would first publish a conference paper and then follow it up with a more comprehensive journal article; it wasn't as bad to limit the length of the conference paper, because the journal article would provide all of the missing details. In today's world, the conference version is almost always the final archival description of a project; thus, we should encourage authors to make conference papers comprehensive. |