day by day: a blog

December 31, 2008

dark, dark, darkling

[image: Noël Kingsley] I got interested, for obvious reasons, in reading Hardy's "The Darkling Thrush". There is a discussion about the poem, initiated by Robert Pinsky, going on at Slate's "The Fray" at the moment. I do not much like the idea of a "Fray" over a poem. Somehow, I think one should aim for comments that have a "take-it-or-leave-it" quality rather than a "let's-discuss" cast. But I contributed something. Here it is:

[image: Noël Kingsley] I got interested, for obvious reasons, in reading Hardy's "The Darkling Thrush". There is a discussion about the poem, initiated by Robert Pinsky, going on at Slate's "The Fray" at the moment. I do not much like the idea of a "Fray" over a poem. Somehow, I think one should aim for comments that have a "take-it-or-leave-it" quality rather than a "let's-discuss" cast. But I contributed something. Here it is:

The strength of any piece of writing lies in its power to generate disagreement. By this measure, "The Darkling Thrush" is strong.

It's a mistake with any lyric to look too rapidly in it for a message or a takeaway. That's the best way to miss such great details as the perceptual sequence by which Hardy's poem so sensitively captures "noticing". He shows that the way people usually see birds is first by hearing "a voice" and only then, by turning their gaze in the direction of the sound and scrutinizing the trees, glimpsing a "gaunt, and small" creature which is singing in a way strangely at odds with its fragile appearance. Then we turn away again or let our minds wander, precisely as the poem does here, because, emotionally speaking, the sound of the birdsong always amounts to so much more than the sight of the bird. Hardy gives us hearing preceding, and succeeding, seeing, which for denizens of a culture obsessed with ocular truth, feels like a moment of liberation.

If I wander around in the interior of the poem rather than rushing banally to its end for the deeply enigmatic conclusion, what strikes me is how complex and obsessive Hardy's fascination with boundaries is here. He sets himself on thresholds of time – large ones, the turn from the 19th to the 20th century, and, more local ones, the transition from day to night. (Incidentally, it's a wonderful "late afternoon" poem; which is a very rare time for poetry to describe, no doubt that's partly the attraction for Hardy.) He also positions himself between spatial axes, leaning, and thus neither fully upright nor prone, and on a spatial threshold – the gate. Moreover, we're at the interface of nature and culture, since a coppice is a small wood, where trees are allowed to grow for the purpose of being periodically cut for human use.

These checks, borders and encountered limits, the varying points of demarcation and contrast, some of which the reader only notices subliminally at first, are what bank up the emotion which is suddenly, almost violently released in that shining word "illimited".

Hardy's speaker – I use that term not to play dull epistemological games but just to gesture towards the exquisite dramatic calibrations Hardy manipulates; this is anything but a spontaneous, unpremeditated overflow of powerful feeling – can't quite bring himself madly, ecstatically to "fling his soul" into the growing gloom in the way the thrush seems to. Nor can he quite make himself step out of the tangible, solid world of fences, paths, hedges. Or liberate himself from well-organized stanzas and rhymes. But the poem trembles at its own brinks, emotional, sensory, literary. Look at those beautifully uncomfortable off-rhymes: "coppice gate"/"desolate" (nobody reading the poem sensitively will say "dess-oh-layte"), "seemed to be"/"canopy", or "among"/"evensong". Or at the way that each of the first two stanzas is made from two relatively crudely soldered-together quatrains, whereas each of the last two stanzas, under the influence of the speaker's simultaneous excitement at and distrust of the bird's song, melts into a single, more fluid, but still not completely deliquescent sentence.

Hardy uses these subtle chafings at self-imposed limits to show his words stretching, deliberately ineffectually, towards the ineffable which can, if conditions are right, be intuited but not spoken. Perhaps that's what modern poetry is? A via negativa, a lonely haunting of once-sacred spots, an overhearing of a strange, unsanctioned music which might or might not any longer be redemptive, a "desolate" searching in the fading light for numinous signs? The authenticity of the experience in "The Darkling Thrush", as in so many Hardy poems, comes not from fulfillment but doubt, not from messages but withholdings, from a mind showing how it is possible to dwell in uncertainties, to find beauty (of a kind) in absences and, if they are seized hold of in language acutely enough, poetry in the very feelings of finitude, incomprehension and unawareness.

Posted by njenkins at 03:32 AM | Comments (0)

December 30, 2008

le Dictionnaire des idées reçues

Genius: Transcendent. "Say what you like about Mozart. The man was a genius!"

Genius: Transcendent. "Say what you like about Mozart. The man was a genius!"

Nature: Restorative. "It's a wonderful thing, Nature."

Modern poetry: Privative. "That's what modern poetry is -- subtractions, demythologizations, a via negativa."

Contributors (in no particular order): my father-in-law, my father, myself.

[Notes: Saw an ugly little Chevy rolling along El Camino this morning – a yellow 'Cobalt' (I thought of Eluard's 'La terre est bleue comme une orange'); in Geoffrey Hartman's Wordsworth's Poetry read a few stunning pages this afternoon on the transcendence of nature; later, on our walk, felt that I heard the creaking of the joints in the wings of the geese passing overhead; as Earth hurtles towards its perihelion, which will be achieved this Sunday morning, Venus is prominent high in the southwestern night sky, Orion shines in the south, Betelgeuse glittering red and Rigel blue, while, far more faintly and much nearer the horizon, Mercury and Jupiter, if I could see them, would look unusually closely conjoined; this is my first post written on an iMac.]

Posted by njenkins at 11:27 PM | Comments (0)

December 14, 2008

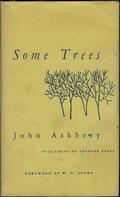

some trees

There will always be researchers and aficionados interested in the Yale Younger Poets series when it was under Auden's editorship in the later 1940s and first half of the 1950s and in particular in the circumstances in which he made his choice for the 1956 award, John Ashbery's book, Some Trees. The title was Auden's suggestion -- Ashbery had originally called the manuscript simply Poems. Time has proved that picking Ashbery was amongst the most spectacular of successes in Auden's many prescient selections.

There will always be researchers and aficionados interested in the Yale Younger Poets series when it was under Auden's editorship in the later 1940s and first half of the 1950s and in particular in the circumstances in which he made his choice for the 1956 award, John Ashbery's book, Some Trees. The title was Auden's suggestion -- Ashbery had originally called the manuscript simply Poems. Time has proved that picking Ashbery was amongst the most spectacular of successes in Auden's many prescient selections.

(When will people stop moaning about their own simple-minded misreadings of what Auden, who had not in the first place wanted to burden Adrienne Rich with an introduction by him to her book, said about Rich in the essay which Yale required him to contribute to A Change of World, and focus instead on the fact that he chose her?)

Recently, one Jascha Kessler, born in New York in 1929 and a professor of English at UCLA since 1961, has sluggishly stirred the Yale Younger Poets pot. In late November 2008 Kessler, a little-studied poet, playwright, novelist and translator, wrote an account for the TLS letters page which explained some of the reaons why Kessler was, in his own view, beaten to the Yale prize by Ashbery. (Kessler had won a Major Hopwood Award for Poetry at the University of Michigan in 1952 but had published nothing in book form in the next few years which is perhaps one reason why he believed himself entitled to the Yale Younger Poets Prize in 1956.) Kessler's TLS explanation of his failing to be selected by Auden has something to do with anti-Semitism on Auden's part and homosexual chauvinism. The ever-interesting Ashbery responded with humour and vigour in the same venue the following week.

In the late spring of 1955 Auden, staying on Ischia, read the submissions, including Kessler's, which Yale University Press had forwarded to him to consider for the 1956 prize. He was dismayed by their quality (as he had been by the submissions the previous year when he had ultimately decided not to award the prize). He consulted with the young Anthony Hecht, who was also on Ischia at the time. Hecht confirmed Auden's opinion, so Auden wired Chester Kallman, who was in New York, asking him to tell Ashbery and O'Hara to send copies of their manuscripts to him on Ischia. Edward Mendelson provides the essential background on the 1956 selection in his notes on pp. 772-773 of volume 3 of Auden's prose in the Princeton edition of Auden's Complete Works. Now, on the New York Times website, Gregory Cowles has an efficient rundown on the recent Kessler contra Auden and Ashbery spat, with links to Kessler's and Ashbery's letters, in "Ashbery and Prizes".

I think it would be fair to say -- speaking figuratively of course -- that during their joust in the TLS lists, the good Sir John unhorsed milord Kessler, then dismounted and rapidly slew his prone and bewildered foe. Finally the white knight took the time to discommode himself sufficiently to be able to, by natural means, irrigate his erstwhile opponent's battered literary corpse, perhaps in the unspoken hope that something rare and beautiful might one day grow from the remains.

There is probably more to be uncovered/discovered at some point about the 1956 Yale prize and, more generally, about Auden, Ashbery, Kallman and O'Hara. But, for the time being, Cowles's account of this impromptu tournament, which took place by an insignificant-seeming crossroads on the way towards the future, bears reading.

Posted by njenkins at 12:35 AM | Comments (0)

December 13, 2008

hamlet

"You tell me that I am 'not accused of anything' but you ask me to give you my recollections of the period early in the Transformation, the run-up to Christmas 2008. Of course that moment is so distant in time now that it is hard to recollect much.

"But at least one memory does stand out. It is of a brisk, December morning when, as usual, I walked my youngest son to school. Times were getting harder economically, and I think everyone sensed that. Edifices, which had once seemed so solid that one had not even considered whether or not they were eternal, stood on the point of collapse. GM, for instance, announced that it was shutting down a third of its factories for a month. We hadn't hit the levels of catastrophe they experienced in Weimar in the early 1920s -- then even the lightbulbs and the doorhandles were being ripped out and taken away. But I remember thinking that the coldness in the air that morning was an analogue of the chill which had settled discernibly on the country.

"Everything felt pinched; people seemed just slightly wary, quieter than normal, introverted, preoccupied with their own thoughts. It was as if everyone had become just slightly more selfish, as a person does, for example, when they start to get hungry, when, you know, the rumbling in your stomach turns into a subtle, dull, enduring ache. We weren't hungry, you understand. But perhaps our spirits were. Anyway, somehow, it felt like that.

"My son and I walked along our street. By any measure except those of the income levels in the surrounding towns we were economically safe, cushioned, even though my wife and I worried about money all the time. Over the preceding weeks, as the rate of autoburglaries had risen sharply in our neighbourhood, I had started surreptitiously to 'check' parked cars for damage.

"We strolled along. We had grown used to passing houses with seasonal decorations and ornaments still glowing in the morning haze -- little strings of illuminated blue icicles hanging from the eaves, ruby-coloured lights wound round tree trunks, that kind of thing. Four of five houses up, on the left, a portly, cross-eyed neighbour, whom I quietly loathed, had set up some a family of glowing, wire reindeer on her lawn. ('For the children', she had simpered to me a few days before.)

"Except that this morning, when we passed her house, the reindeer were gone. The indentations made by their hooves on the frosty grass, like a fragile set of fingerprints, were still there, the little pressed-in shapes preserved for a while at least by the crystals of frozen dew which had formed round the hooves. But the metal animals themselves had vanished. Owen bowled on by without any comment. But I found myself lingering, thinking at first, as was my habit then, aesthetically, gazing at the view appreciatively as a scene of pure emptiness. Then I realized what had happened. The reindeer had been stolen. And that seemed eerie and slightly menacing to me. Even the cheap gimcrack-ornaments, surely almost worthless, were being taken away. We had come to that. Then I came to myself, picked up my pace and reached Owen before the crossing.

"I have come to feel that events of this kind -- so trivial in the light of what even then we understood about what was happening -- were not really to do with the simple desire on someone's part to make some fast money. How could that explain these stolen reindeer? No, instead this had to do with the moods of vengefulness and random destructiveness which we were all gradually, and to a greater or lesser degree, falling prey to. This was a glimmering of anarchy.

"For some people -- perhaps many for all I know --, these feelings of anger and destructiveness remained purely private, promptly suppressed by their consciences from articulation even, let alone carried over into action. Or checked by social protocols. Looking back now, though, I think that we were all in some sense paying for something we had been complicit in. Which of us escaped whipping in what followed? And which of us deserved to? People who came through unscathed were people who were merely lucky. Their being unscathed was morally meaningless.

"I recollect most strongly that as I stood staring at the reindeer prints on that little lawn on that frosty morning, I had the sudden conviction that at some deep spiritual level we were thieves whom other thieves were robbing. Our god was the dollar, our evangelist was Hobbes. And this was our mean new world....

"Oh, it is all very inadequate, I know. But I cannot explain it any better than this. There it is. These are the memories I can speak of. I have told you what I can bear to remember. This is my version of the truth. And, now that I have complied with what you asked me to do, I would like to be silent. Ah, but wait, one other small thing: I do recall as well that the next day there were rumours from a block not far off that a pile of ashwood intended for the family's private fire had disappeared from a front yard. You see? Christmas 2008, yes, it was the season of disappearances, like a parody of an advent calendar, in which every day a door closed and something that had been present dissolved into thin air.... But enough. Obviously, one now sees these were just tiny symptoms of the playing out of an enormous process which we had absolutely no way to grasp. It was a process which you know as well as I do would crack many hearts."

Posted by njenkins at 02:12 AM | Comments (0)

December 11, 2008

a changing of the guard

[image: Jean-Paul Laurens, La Mort de Tibère (1864)]

[image: Jean-Paul Laurens, La Mort de Tibère (1864)]

Like many small men, I have been enjoying reading today about the death of a tyrant, Tiberius, the second Emperor of Rome.

Here is the passage; it is from Tacitus's Annals, bk 6, in the newly ancient translation of Alfred John Church and William Jackson Brodribb (their wonderful 19th century language sports handlebar moustaches and a central parting). Tacitus describes the despicable Praetorian prefect Quintus Naevius Sutorius Macro doing the right thing at Misenum in March, 37 AD:

"Tiberius's bodily powers were now leaving him, but not his skill in dissembling. There was the same stern spirit; he had his words and looks under strict control, and occasionally would try to hide his weakness, evident as it was, by a forced politeness. After frequent changes of place, he at last settled down on the promontory of Misenum in a country-house once owned by Lucius Lucullus. There it was noted, in this way, that he was drawing near his end. There was a physician, distinguished in his profession, of the name of Charicles, usually employed, not indeed to have the direction of the emperor's varying health, but to put his advice at immediate disposal. This man, as if he were leaving on business his own, clasped his hand, with a show of homage, and touched his pulse. Tiberius noticed it. Whether he was displeased and strove the more to hide his anger, is a question; at any rate, he ordered the banquet to be renewed, and sat at the table longer than usual, by way, apparently, of showing honour to his departing friend. Charicles, however, assured Macro that his breath was failing and that he would not last more than two days. All was at once hurry; there were conferences among those on the spot and despatches to the generals and armies. On the 15th of March, his breath failing, he was believed to have expired, and Caius Caesar was going forth with a numerous throng of congratulating followers to take the first possession of the empire, when suddenly news came that Tiberius was recovering his voice and sight, and calling for persons to bring him food to revive him from his faintness. Then ensued a universal panic, and while the rest fled hither and thither, every one feigning grief or ignorance, Caius Caesar, in silent stupor, passed from the highest hopes to the extremity of apprehension. Macro, nothing daunted, ordered the old emperor to be smothered under a huge heap of clothes, and all to quit the entrance-hall."

What a relief to find someone "nothing daunted." What a pleasure to read about an emperor, almost a god, being mundanely suffocated with a "huge heap of clothes." Tiberius was succeeded by his adopted grandson, Gaius Julius Caesar Germanicus, the third Emperor, better known as the hyperthyroidic, epileptic tyrant Caligula, who was wont to talk to the moon. A multitude of conspiratorial swords brutalized Caligula in 41 AD.

Posted by njenkins at 02:47 AM | Comments (0)

December 03, 2008

connections

This will be my shortest ever (now, and in time to come) article on Auden, though it has involved a monumental amount of research and many accidental discoveries of a surprising kind. In fact, the "article" reduces to no more than this lean diagram.

This will be my shortest ever (now, and in time to come) article on Auden, though it has involved a monumental amount of research and many accidental discoveries of a surprising kind. In fact, the "article" reduces to no more than this lean diagram.

Does it signify anything? The conventional answer is -- no. That means the "poetic" answer is -- yes. But what? You tell me. I am not a poet; I am baffled. Still, it is success of a kind simply to be able to frame a simple question. If only half the paragraphs I write, or read, did as much.

There is a seedy prestige (and a sort of madness) in trying to make things more complex than they are. It is harder to make things simple. Estrangingly simple. Simplicity is a goal, as in a statement that is only a diagram.

Posted by njenkins at 05:52 PM | Comments (0)

With the exception of the interspersed quotations, all writing © 2007-10 by Nicholas Jenkins [back]