day by day: a blog

October 24, 2008

minard's eternal silences

[Image: Charles Joseph Minard, "Carte figurative des pertes successives en hommes de l'Armée Française dans la campagne de Russie 1812-1813"]

[Image: Charles Joseph Minard, "Carte figurative des pertes successives en hommes de l'Armée Française dans la campagne de Russie 1812-1813"]

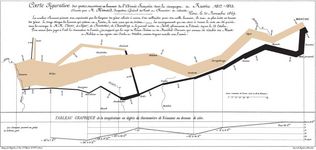

Yes, one thing does lead to another. It is impossible to draw up a map of any kind (as I did yesterday in "Homage to War and Peace") concerning the invasion of Russia by the French Army during 1812 without invoking memories of one of the greatest of all information graphics, the "Figurative Map of the Successive Losses of Men in the French Army during the Campaign in Russia 1812-1813" (1869).

The "Map" was created by the civil engineer and cartographer Charles Joseph Minard (1781-1870) after he had retired from a position as a general inspector in the French government's "Corps des Ponts". Published on the eve of the Franco-Prussian War, less than a year before Minard's death, this potently lucid graphic work, in the words of one of Minard's obituarists, "inspires bitter reflections on the cost to humanity of the madnesses of conquerors and the merciless thirst of military glory" (Annales des ponts et chaussées, 1871). The great chronophotographer Étienne-Jules Marey said that Minard's chart "defies the pen of the historian in its brutal eloquence."

The "Figurative Map" dramatizes statistically the period between 24 June 1812 when, using Minard's figures, some 442,000 of Napoleon's troops crossed the Nieman and entered Russia to mid-December of the same year when what still passed for the French Army, now reduced in number to some 10,000 or so shattered souls struggled back across the Nieman's ice. (Modern estimates suggest that somewhere between half a million and 690,000 French and allied troops surged into Russia during the summer of 1812 and that about 400,000 of them died there in the next six months.)

Minard's work tracks three variables: 1) the size of the army at any given point; 2) its location and the direction it was moving in; and 3) the declining temperatures that took hold during the Army's apocalyptic disintegration and retreat out of Russia, which occurred between 19 October and 14 December 1812.

Critics often note the special significance of rivers in Minard's work. The most obvious instance is the sanguinary crossing of the Berezina, which took place in sub-zero temperatures between 26 and 29 November, when troops commanded by Kutuzov, Wittgenstein and Chichagov killed roughly half the remnants of the French Army either in, or on the banks of, the river as it attempted to scrabble across two 100 metre pontoons General Eblé's engineers had cobbled together in spite of frostbite, exhaustion and heavy enemy fire. Minard's black line, "one millimetre for every ten thousand men", shows some 50,000 approaching the Berezina and, with a sudden ugly contraction, some 28,000 departing from it. There is a special pathos in reading a professional bridge engineer's dispassionate graphic account of a human disaster on such a scale taking place where a river is crossed.

Given such a masterwork, all accurate observations, even critical ones, are a form of implicit celebration. Here are mine, largely inspired by the "Map"'s silences and occlusions.

- The name "Napoleon" appears nowhere on the "Map". Nor is their any indication of one of the most momentous and (in Tolstoy's eyes, shameful) actions Napoleon performed during the entire campaign: his abandonment of his starving and freezing soldiers and his secretive flight back to France which began on 5 December 1812.

- Battles and skirmishes are virtually invisible on Minard's "Map". Instead, he presents an image of the river-like, quasi-natural, and therefore morally innocent, flow of the French Army into and out of Russia.

- Time is not treated with rigour or on a consistent scale. It took the French Army slightly more than two and a half months to march from the Nieman to Moscow (Napoleon entered the Russian capital on 14 September 1812) but slightly less than two months to retreat from Moscow to the Nieman (Napoleon withdrew from Moscow on 19 October 1812). Yet Minard's "Map" allots the same amount of space to two events, the drive into Russia and the drive out, which consumed different amounts of time. The roughly five weeks which the French Army spent in a state of exhausted inertia occupying Moscow are not represented in any legible form.

- The decision to emphasize the temperatures which occurred during the retreat out of the country is complicit with the myth Napoleon himself subsequently promulgated: that he had been beaten by the Russian winter, not by the Russians. It has the further effect of throwing greater emotional weight onto the heroic abjection of the retreat than rather than the brutal aggression of the advance.

- This, itself, is mystificatory: in fact the greatest losses were suffered on the march into Russia and before any large scale combat happened, as typhus, dysentery, starvation, suicide and desertion reduced the French Army from (using Minard's figures) 442,000 to 127,000 before the first major battle, the Battle of Borodino or, as the French called it, "la bataille de la Moskowa", took place on 7 September 1812. Days of heat, rain and dust, not snow and ice, were the conditions under which most of the French soldiers died. One study, by an army academic, notes: "the main body of Napoleon's Grande Armée, initially at least 378,000 strong, diminished by half during the first eight weeks of his invasion before the major battle of the campaign. This decrease was partly due to garrisoning supply centers, but disease, desertions, and casualties sustained in various minor actions caused thousands of losses. At Borodino on 7 September 1812 - the only major engagement fought in Russia - Napoleon could muster no more than 135,000 troops, and he lost at least 30,0005 of them to gain a narrow and Pyrrhic victory almost 600 miles deep in hostile territory. The sequels were his uncontested and self-defeating occupation of Moscow and his humiliating retreat, which began on 19 October, before the first severe frosts later that month and the first snow on 5 November" (Allen F. Chew, "Fighting the Russians in Winter: Three Case Studies"). Although Minard's "Map" allows anyone who looks at it carefully to glean some (but not all) of this information, its semiotics divert attention away from these truths, towards a myth of non-aggressive resilience as the Army withdraws from Russian territory under extremely arduous conditions.

- The "Figurative Map" is profoundly parochial in its treatment of suffering. The most deafening of all Minard's graphic silences concerns Russian death and suffering. In this version of the campaign, only the French die. But a reasonable modern estimate suggests that the Russian Army lost some 210,000 men on their home soil fighting the French and that, in addition, hundreds of thousands of Russians civilians died in the fiery paths carved out by the French through the Russian countryside. Nothing in Minard's beautiful, circumspect graphic lucidity even gestures towards that reality.

Minard's "Figurative Map" is an incomparable piece of graphic rhetoric. But, like all rhetoric, its success lies as much in veiling as in revelation. It was therefore fortunate that in 1869, the same year in which Minard published his gallocentric "Map" of hygienic but "brutal eloquence", Tolstoy righted the balance by completing and publishing the final installment in his ragged, loose, howling, chauvinistic and equally mystificatory epic of Russian suffering. Juxtaposing these two works, image is incommensurate with text. Minard and Tolstoy left us a "firm, French order" pitched against a "quite different", "Russian order of life", a system opposed to a vital anarchy, a cry of the soul to counterpoint the sombre, refined muteness of the spirit.

Tolstoy wrote in War and Peace that "there is no greatness where simplicity, goodness, and truth are absent." So far, so good. But one may also wonder whether there is "greatness" where "simplicity, goodness, and truth" are too visibly and exclusively present. "The Figurative Map" and War and Peace both say, No.

Posted by njenkins at October 24, 2008 02:49 PM

With the exception of interspersed quotations, all writing is © 2007-09 by Nicholas Jenkins