commentary: "w. h. auden - family ghosts" website

Contents

- Detail

- "The Intellectual Aristocracy"

- Audens: Rootedeness

- Bicknells/Birches: "Influence"

- Births and Deaths

- Religion: Anglicans

- Religion: Quakers

- Poets

- Slaves and Poetry

- And Next?

Detail

"Family Ghosts" aims, by providing a completely new level of detail about W. H. Auden's immediate family background, to supplant the vague generalities offered in the existing biographies. So, for the first time, all 30 of his immediate ancestors (parents, grandparents, great-grandparents and great-great grandparents) are named. In addition most of their dates of birth, marriage and death as well as the places where those events occurred are listed. This is also the case for all 14 of Auden's uncles and aunts.

"Family Ghosts" also provides copious new details about such important but previously enigmatic figures within the Auden biography as Margaret Marshall, the psychiatrist who seems to have conducted some kind of analysis on Auden in Spa, Belgium in 1928 and who shortly afterwards was briefly and very unhappily married to his brother John Auden.

But, in a more general sense, "Family Ghosts" is part of an attempt to re-embed W. H. Auden in English, American and German history, in this case by showing the extent (in terms of social space) and the nature (in terms of cultural positioning) of his ancestry and familial relationships. Up to now, as any reader of the main Auden biographies can rapidly discern, very little indeed has been known about Auden's family history. "Family Ghosts" changes that. The database currently contains over 1,200 names and is therefore a site as much about class, religion, culture and social patterns in those societies mentioned, and especially in English society during the 19th and early 20th centuries, as it is about a single individual or one isolated family. This sprawling web of data thus links the Tudor poet Henry Howard; the 20th century physicist Werner Heisenberg; William the Conqueror; John William Birch, a Governor of the Bank of England in Victorian England; Maria Riddell, the poet and close friend of Robert Burns; the painter John Constable (a relative of both the Bicknells and, more distantly the Birches); E. F. Schumacher, the "Small is Beautiful" prophet; and Sir Henry Firebrace, who in 1649 accompanied Charles I to the scaffold where the king was beheaded.

To find out how any individual listed on the website was (or is) related to Auden, from the "Charts" button" towards the top left of the homepage, select "Relationship Chart" on the dropdown menu. Auden's ID is "I5". On the page which clicking "Relationship Chart" brings up, put "I5" into the box for Person 1 or Person 2. Click on the other box's figure icon and use it to find the unique identifying number for the other person in the relationship you want to have described. For example, "I2" is the ID of Constance Rosalie Bicknell, Auden's mother. Make sure that the second ID number is present in this empty box. Then click "View" and the database will return an answer, elaborate or simple depending on the case, to your question.

The comments below assume in the reader a basic interest in, and some familiarity with, the website "W. H. Auden — Family Ghosts". If you have not already done so, it would make sense to make a brief visit to the site before returning, if you choose to, and reading what I have to say here.

"The Intellectual Aristocracy"

"Family Ghosts" is a critical and historical undertaking. Above all, it is not about the irrational or mythic associations of "blood" or "line". Over time, the vast social network of a family, extending as it does both laterally through social space and horizontally through historical time, creates a very specific culture within which its members shape themselves. For this reason, the "Family Ghosts" website is about culture, class, social patterns, focussed through the lens of the Auden family.

In an interview which he gave early in 1963, Auden remarked that he had realized during the writing of The Ascent of F6 in early 1936 that he would have to leave England: "F-6 was the end. I knew I must leave when I wrote it. And, and this is off the record, I knew it because I knew then that if I stayed, I would inevitably become a member of the British Establishment. It is impossible not to there." Auden's fear of becoming a member of the "British Establishment" is familiar to readers in a vague, general way. But how deeply, and in what ways, was Auden already embedded in the class structure of English life when he struggled with the pull of cultural co-option in 1936? Because of a lack of detailed knowledge about Auden's family background, precise answers to that question have remained almost, or completely, nonexistent. "Family Ghosts" lays bare answers to those questions.

It is now easier to appreciate the force of comments such as this one reported by Cyril Connolly in 1947: "[Auden] reverts always to the same argument, that a writer needs complete anonymity, he must break away from the European literary 'happy family' with its family love and jokes and jealousies and he must reconsider all the family values" or this one, made in the mid-1960s: "I left England because there the cultural family is so small. While I love my cultural cousins and aunts very much, while I adore the cooking and the climate, it is rather small for living in all the time." For Auden, the "happy family" and the national culture did overlap significantly.

One broad conclusion which the data assembled in "Family Ghosts" suggests is that on both his paternal and maternal sides Auden's family was profoundly entrenched in particular sectors of the "Intellectual Aristocracy" which Noel Annan identified as a fundamental presence in late 19th century and early 20th century British cultural life. (See N. G. Annan, "The Intellectual Aristocracy" in J. H. Plumb, ed., Studies in Social History: A Tribute to G. M. Trevelyan (London: Longmans, Green, 1955), 243-87.) Annan pointed to the densely developed family networks which linked Whig intellectuals with such prestigious names as Trevelyan, Macaulay and Stephen. Extending Annan's point, it is possible to see how even amongst less well-known families of the intellectual and financial elites existing connections helped to structure individual lives.

Auden's father's name was George Augustus Auden, his mother's was, as noted above, Constance Rosalie Bicknell. Here, then, is the Annanesque story of an interconnected "intellectual and financial aristocracy" seen in terms of the Auden-Bicknell marriage. George Augustus Auden (b. 1872) was training in London as a doctor in the mid-1890s. Constance Bicknell (b. 1869) was training as a nurse in London in the mid-1890s. How might they have met? A chance encounter in London medical circles? That is the conventional story (as related, for example, by Auden in "Letter to Lord Byron"). But it is more than likely that there were social and business connections between the Birch/Bicknell family circles and the Auden family circles before George Auden and Constance Bicknell met and courted (and eventually married in 1899). As so often happened with families and marriages at this period when people tended to marry within pre-existing networks of relations, this couple did too.

Constance Bicknell was a first cousin of Francis Mildred Birch (b. 1862). Birch was a partner in the stock broking firm of Francis Birch and Christian, in London. In 1896 Charles Henry Pasteur (b. 1869) was made a partner in that same firm of stockbrokers. Now, Pasteur was the younger brother of Isabel Twigg née Pasteur (b. 1858), who had married John Hanbury Twigg (b. 1856 in Repton) in London in 1894. Margaret Auden, née Twigg (b. 1858), John Twigg's sister, was married in 1886 to Rev. John Auden (b. 1860), the oldest brother of George Augustus Auden. In other words, George Auden's sister-in-law was the sister of a man who was a partner in Constance Bicknell's cousin's business. There were thus quite close links between the Birch/Bicknell and Auden families before the courtship of Auden's parents.

Given that in a city of the hugeness of London, these two families (out of all the possible permutations of family alliances) should have had such links, consolidated in the mid-1890s, and that another link between them, in the form of a marriage between George Auden and Constance Bicknell, should have been added at the end of the 1890s is an important and hitherto unknown facet of the Auden family's history. The links between Auden and Bicknells/Birches were not, of course, the reason why the pair fell in love — why, as Auden put it in "Letter to Lord Byron", "A nurse, a rising medico, at Bart's | Both felt the pangs of Cupid's naughty darts" — but it must have been a contextual influence in the romance.

Here, then, is the basic matrix of social and economic interconnection, first codified by Annan, in which intellectually-inclined, professional English families of the middle and upper-middle class tended to intermarry on multiple occasions with other families from the same class. In W. H. Auden's case, though, the branches of the intellectual aristocratic tree to which the Audens and Bicknells joined were very different ones than that Whiggish branch on which Annan concentrated. In Auden's case, the Auden and Bicknell branches both stemmed from "boughs" which were more radical and more clearly Tory. As this example shows, "Family Ghosts" not only provides a great deal of new information about Auden's social background. It also amplifies the scope of portrait which Annan painted.

"Family Ghosts" shows as well that, to a far greater degree than Auden and his early biographers acknowledged, or than Auden himself probably knew or guessed consciously, the Auden/Bicknell families had deep links with some of the formative figures and families of English cultural life of the last three centuries. For instance, the database demonstrates that although it was Christopher Isherwood who monopolized the "I am a camera" slogan in his writing, it was actually Auden who was distantly related to the great early photographer (considered by many the as inventor of photography), Henry Fox Talbot.

It was the very force of those sorts of connection with the "British Establishment" which, by counter-reaction, eventually propelled Auden away from the British cultural mainstream. But we cannot understand his subsequent alienation from England and its culture without first understanding his initial embeddedness in it. This is what "Family Ghosts" allows one to do.

The Audens: Rootedness

Dr. Auden enthusiastically imbued his son with a "Nordic" myth of his family origins and it was a belief sustained by his son throughout his own career. He commented near the end of his life: "My father brought me up on [the Icelandic sagas]. His family originated in an area which once served as headquarters for the Viking army." Doubts have occasionally been cast on the validity of this genealogical narrative. "Family Ghosts", based as far as possible only on reliable documentary evidence, neither confirms nor refutes Dr. Auden's claims about Viking ancestry. However, the earliest Auden we have been able to trace is William Auden (1726-1794) who was born and who died in the Midlands village of Rowley Regis (the "Regis" indicates that the area was originally owned by the King) not far from Birmingham. Ancestors with different surnames living in the same town or general area can be traced much further back.

In "Letter to Lord Byron" Auden alludes to this base in middle England: "My father's forbears were all Midland yeomen | Till royalties from coal mines did them good." The most striking demographic characteristic of Auden's ancestors on the paternal side is their profound rootedness in one particular, not very large area of the English provincial world, even their immobility there in the "Black Country".

There had been Audens, or families who were or would become relatives of the Audens, in the Midlands since the 16th century. The first such traceable ancestor is Margaret Woodhouse (1540-1615) who died in Rowley Regis, Staffordshire, a town in which Audens and their relatives would later live for centuries. The hard rock of Rowley had been known as far back as the Roman period, and there were many quarries in the vicinity. Here is Anthony Andrews: "In the 18th century, Oldbury and Rowley Regis began to expand, the main reason for this being the construction of canals and the exploitation of local deposits of coal and iron. Industries sprang up, such as Phosphorous Works, Chemicals, Tar Distillers, etc. All landowners retained their Mineral Rights. Among other items produced were boilers, bricks and [eventually] even first World War tanks. By 1880, there were over fifty collieries and four blast furnaces in Rowley Regis." These remarks are in perfect alignment with what one tourist website mentions, commenting that: "The town's first industries were nail making and coal mining, which started in the 13th century, by the 19th century chain making… was also a major employer." (The town is mentioned in Auden's 1932 poem beginning "O Love, the interest itself in thoughtless Heaven": "upon wind-loved Rowley no hammer shakes | The cluster of mounds like a midget golf course.") A love of geology, which had such a profound impact on the imaginations of both W. H. Auden and his brother John B. Auden, who was one of the greatest geologists of his generation, contained a long-held familial aspect. The Audens had been involved with exploitation of rock and fossils for at least two centuries; and the family's identity was tied up with mining.

Margaret Woodhouse was the great-great-great-great-grandmother of the poet James Woodhouse (1735-1820). (The latter was Auden's first cousin four times removed: James Woodhouse's cousin Phoebe Woodhouse (1758-1828) married John Auden (1758-1834) in Rowley Regis in March 1782 and this couple were Auden's great-great-grandparents.) James Woodhouse was born on a farm which had been in his parents' family since the 1530s. Even after attaining a measure of renown in metropolitan literary circles, Woodhouse remained a distinctly provincial figure to his more sophisticated, or effete, contemporaries. According to his grandson, the Rev. R. I. Woodhouse, when Woodhouse had begun to move in London circles, his "clear sonorous voice, and his primitive haths and doths and his hast thous and wilt thous" were still notable.

Both in being involved with cultural pursuits and in moving to London as an adult, James Woodhouse was an anomaly in Auden's family background. As far back to the Nicklins, Audens and the Woodhouses of Auden's great-great grandparents' generation — the one born in the last half of the 18th century — the vast majority of Auden's ancestors on his father's side came from, and lived in, Staffordshire or Derbyshire.

The first person with the surname "Auden" who is known to have been born in Rowley Regis was William Auden (1726-1794), who in 1753 married Esther Sorrell (1734-1804) from nearby Halesowen. This pair formed one set of Auden's great-great-great grandparents on the paternal side. It is almost certain that William Auden made the money which allowed him to buy his family a coat of arms from the mining industry in Rowley Regis. Another set of great-great-great grandparents, Samuel Nicklin (1795-1866) and Phoebe Auden (1797-1856), both died in Rowley Regis. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Auden's relations on his father's side remained extraordinarily rooted in the Midlands, principally in the area just to the west of Birmingham (Rowley Regis) and then from the mid-19th century to the south-west of Derby (the Rolleston/Burton-upon-Trent/Church Broughton/Repton area).

It was at the latter period that two Auden brothers, the Rev. John Auden (W. H. Auden's grandfather) and the Rev. William Auden, moved across the Midlands to marry two sisters of the wealthy Hopkins family of Dunstall Hall, Staffordshire. The Rev. John Auden married Sarah Eliza Hopkins in 1859 and the Rev. William Auden married Mary Jane Hopkins in 1861. William and Anne Hopkins, the parents of the Hopkins sisters, were landowners in the Dunstall area, and they were rich enough to provide local Church of England livings for both of their sons-in-law, for John in Horninglow and for William in Church Broughton. It seems likely that it was Sarah Eliza Auden who, after her husband's death, purchased "Danesgate", a house in Repton, probably sometime in the early 1880s, which has remained in the Auden family until the present time. It is also probable that the combination of mining royalties from the Rowley Regis area from the Rev. John Auden's family and of money from houses and land from Sarah Eliza Auden's family sufficed to provide modest private incomes for the seven children of John and Sarah Auden who survived into adulthood. George Augustus Auden, W. H. Auden's father, may have used his to supplement the probably somewhat meagre municipal salary he received as the Chief Medical Officer of Birmingham. W. H. Auden's parents were unconventional in many ways, but their independence of mind was buttressed, at least in part, by the profits canny businessmen and administrators had accrued in the not far-distant family past.

View Larger Map

Auden's ancestors -- "Auden side"

Auden's grandparents were Rev. John Auden (1831-1876), born in Rowley Regis, and Sarah Eliza Hopkins (1838-1925), born in Rolleston. The Rev. Auden became the Vicar of nearby Horninglow, Staffordshire, where Auden's father was born. Indeed, Dr. Auden was one of eight siblings, seven of whom were born in Staffordshire (and five of whom, including Dr. Auden, were born at Horninglow). Mrs. Auden died in Birmingham, and at least five out of Dr Auden's generation of eight (including Dr. Auden) died in either the Rowley or Rolleston areas, which are, in any case, less than 30 miles apart. Thus, when Auden's father took a job in Birmingham in 1908 he was in essence returning, like a prodigal son, to his family roots. Solihull, where Dr. and Mrs. Auden settled in 1908 is about 12 miles from Rowley Regis.

This earlier deep rootedness is all the more striking then when one sees how profoundly (and typically) the 20th century changed demographic patterns for the family. All of Dr. and Mrs. Auden's three children spent significant amounts of their adult lives abroad (Bernard Auden in Canada; John Auden in India, and Wystan Auden in the United States) and none died or was buried in the Midlands.

Though provincial, rooted, and having a few working-class relatives, such as the young James Woodhouse, the Audens were by and large not poor. Indeed, William Auden (1726-1794) owned or leased mines in the Rowley Regis area and purchased a coat of arms for the family, entitling them to a listing, which has reappeared in subsequent editions up to the present day, in Burke's Landed Gentry. Like all of his brothers and sisters, Dr. George Auden had a modest private income. And one of Dr. Auden's older brothers, T. E. Auden, a solicitor, enjoyed a kind of "Huntin', Shootin' and Fishin'" existence, blasting away at stag each year on Mull in the Hebrides.

This contrasts strongly with Auden's own need to make money, and also makes his propertylessness for most of his life, until 1957 when he bought his cottage in Kirchstetten, more striking. (In this, he was strangely similar to T. S. Eliot, who though a promulgator of settled life in a rural world, was a city-dweller who, as far as I know, never owned any real estate.) But, then in the early 20th century Auden was a freak within the Auden family in many ways. The poet James Woodhouse aside, until Dr. Auden's own generation, when, for example, he and his brother, Dr. Harold Auden, both joined the "Viking Club", an organization devoted to the study of Viking civilization in Britain, the Audens' connections with a wider intellectual and cultural life appear to have been limited or virtually non-existent. The side of the family with multiple artistic, mercantile or social connections, the side which had left a mark on national cultural and political life, was Mrs. Auden's.

Bicknells/Birches: "Influence"

In the same "late" interview in which Auden explained his father's family's Viking origins, he also extended his "nordic myth" to his mother's family: "My mother['s family] came from Normandy — which means that she was half Nordic, as the Normans were...." I note below that the Birches had the most elevated links with the Normans. But what Auden also seems to refer to here, in relation to the Bicknells, is an idea, codified in the family historian Algernon Sidney Bicknell's Five Pedigrees: Bicknell of Taunton, Bicknell of Bridgwater, Bicknell of Farnham, Browne-Le Brun-of France and Spitalfields, Wilde of High Wycombe (1912), a book which Auden may have known at either first- or second-hand. (OED: Norman: "a member of the mixed Scandinavian and Frankish people who settled in Normandy from the early 10th cent.) Bicknell traced the family surname back to the de Pavilly and de l'Estre families who came to England with William the Conqueror in the 11th century and who settled in Somerset, where, around 1240, Robert de Pavilly changed him name to Robert de Bykenhulle after Beacon Hill near Taunton, the land of a manor which he owned.

Auden's mother belonged to the "Farnham Bicknells", a different family line which Algernon Bicknell located in Surrey. But he tendentiously asserted that the fact that this was "a branch of the original families in Somerset is unquestionable", thus implying that Mrs. Auden's roots were ultimately Norman too. In addition, when Auden mentioned that his mother's family was Norman, he may also have had somewhere in his mind the fact that (as Algernon Bicknell also recorded) Selina Acton Birch, Auden's grandmother claimed descent from John of Gaunt. Gaunt (1340-1399), born in Ghent, was the son of Edward III of England and Philippa of Hainault. As we will see below, Selina Birch was essentially correct: the Birches were descended from the Duke of Gloucester, Gaunt's younger brother. So through both the Birch and Bicknell sides Auden's fable of origins obliquely made even his mother's family of ultimately Scandinavian origins. (The name "Norfolk", where Mrs. Auden was born, has its etymological in the Old English word for "northern people".)

Such assertions, though based in fact, belong as much to myth as to history. In more empirically verifiable terms, it is true to say that the differences between the two families are more evident than their similarities. If the paternal side of Auden's ancestry clung grimly to the West Midlands, the maternal side of the family was more far-flung, mostly less settled, and predominantly originated further south and in London and the eastern part of England, closer to the centres of financial and political power. The majority of Auden's great-great grandparents on his mother lived in London, Kent or Essex, but the marriage of John Brereton Birch (1766-1829) and his Louisa Judith Rous (1770-1804/1805) who lived in India, where he was Deputy-Governor of Chandernagore, is a symbolic reminder of the deep involvement of the Bicknells and Birches with colonial India and, more generally, with the administration of the British Empire.

Auden's ancestors -- "Bicknell side"

The family had a grandiose sense of its importance. Auden related that "At the time my mother married [Dr. Auden], medicine was not considered one of the respectable professions. One of her aunts told her shortly before the wedding, 'Well, marry him if you must, but no one will call on you!'" Even though some in the Bicknell family considered that Mrs. Auden had married beneath her station, Mrs. Auden maintained a strong sense of her family's social distinction from the masses. She once asked her granddaughter Jane Auden (later Hanly): "'Are you not glad that you have a name like Auden and not Smith?'" Mrs. Auden might have may have inherited this snobbery from either the Bicknell or Birch sides of her family. As mentioned above, her mother, Selina Acton Birch (1829-1880) claimed that she was descended from John of Gaunt (1340-1399) and hence from royalty. This proves to be a verifiable assertion. (Auden's most distant traceable blood relation comes from his father's side of the family: William Cocus (b. 1160) of Womborne in Staffordshire, his 22nd great-grandfather.) "Family Ghosts" shows that by marriage Auden was directly if distantly related to Sir Henry Firebrace (1619-1691). He was "Honest Harry", an ardent Royalist, one of Charles I's closest friends, and one of the small coterie of supporters who in January 1649 accompanied the King to the scaffold, where the doomed man presented Sir Henry with a diamond ring. The relationship was, predictably, through his mother's side, the grander one.

Indeed, it was his through mother's family that Auden had familial connections with many important intellectual and artistic figures: for instance, the art-historian John Pope-Hennessy (1913-1994) and his brother, the writer James Pope-Hennessy (1916-1974), were his second cousins. In addition, Auden's ancestors, or relations through marriage, on the Bicknell side included the artist John Constable (1776-1837), whose wife, Maria (1788-1828), was a Bicknell); the inventor of photography Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877); the 18th century Tory jurist and politician Sir John Comyns (1667-1740), Auden's great-great-great-great-grandfather; the poet Maria Riddell (1772-1808); John Zephaniah Holwell a survivor of the "Black Hole of Calcutta" who wrote a famous and flagrantly controversial account of the episode; John Holwell (1649-ca.1686), the 17th century astrologer and mathematician; and Francis Lyall Birch (1889-1956), the Second World War cryptographer.

"On the whole, the members of my father's family were phlegmatic, earnest, rather slow, inclined to be miserly, and endowed with excellent health; my mother's were quick, short-tempered, generous, and liable to physical ill-health, hysteria, and neuroticism. Except in the matter of physical health, I take after them." Auden suggested in his 1964 essay "As It Seemed to Us" that the Bicknell/Birches showed all the characteristics of the "artistic" temperament ("quick… generous… liable to physical ill-health, hysteria, and neuroticism"), and this is true. But he could also have added that they were also abnormally rich and influential, as "aristocratic" as they were "intellectual". For example, among the aunts and uncles, great aunts and great uncles on his mother's side were: Henry M. Birch (1820-1884), who was a tutor to the Prince of Wales; Lydia Birch (ca. 1823-ca.1900) who married the Lord of the Manor of Hunston; John Birch (1825-1897), Governor of the Bank of England in the mid-19th century; Ernest Birch (1829-1909) was a Judge of the High Court of Calcutta; and Sir Arthur Nonus Birch (1837-1914) was a Lieutenant-Governor of Penang and later of Ceylon. Auden's second great granduncle, Charles Bicknell (1751-1828), had been the solicitor to the Admiralty; and John Henry Stopford Birch (1883-1949) was His Majesty's Envoy Extraordinary in Central America in the 1930s.

However, by far the most striking connection which Auden acquired through the Birch family is with English royalty, exactly as Selina Acton Birch claimed. W. H. Auden was a direct descendant of William the Conqueror (the King's great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-

great-great-great-great-great-great-[25th great]grandson). He was also directly descended from every Plantagenet king of England from Henry II to Edward III. If Mrs. Auden imbued any of this family history into her son's mind, it is easy to see how profound a symbolic significance might have attached psychologically to Auden's decision to "break away" from England in 1939 and to live "without roots".

Discounting Auden himself and his brother John as well as the Audens' royal ancestors, many other members of Auden's extended family receive entries in the Dictionary of National Biography (none of whom, incidentally, is listed as a relation of Auden's) including: Francis Lyall Birch, Sir Richard James Howell Birch, Sir John Comyns, John Constable, John Holwell, John Zephaniah Holwell, James Pope-Hennessy, John Pope-Hennessy, Maria Riddell, Henry Fox Talbot and James Woodhouse. Of these figures, only the latter comes from Auden's father's side of the family. So, when Auden rejected his already secured place in English cultural life around 1936 and began to travel incessantly and to live abroad for most of the time, he was rejecting a world associated far more with his mother than with his father.

In considering the socially exalted nature of the Birches and Bicknells, one might object that genealogy and family history is an overwhelmingly middle-class affair and that it distorts history by isolating for memorialization those in society about whom careful records were kept, that is to say, those of the middle and upper classes. This is fair. But in the case of the Audens, and, especially, of the Bicknells, the truth seems to be that, with a few exceptions (for example, the Woodhouses) amongst the more than 1,200 names listed here, there were hardly any labouring or working people in the many branches of Auden's family tree. The Audens, and to an even greater extent, the Bicknells/Birches, were from generation to generation overwhelmingly upper-middle class — a confirmation of the enduring stability of that educationally, financially and culturally stratified world from which Auden and his brothers sprang and which critics and biographers ignore at their own cost.

What complicates the picture in the case of Auden's mother's family is that, as Auden himself noted, the Bicknells and Birches, his mother's side of the family, were "liable to physical ill-health, hysteria, and neuroticism." In fact, to be blunter, they tended to die relatively young. There were frequent deaths in the world in which Auden's mother grew up compared with the comparatively "safe" world of his father's childhood. A threatening but suggestive nexus of culture, political or social influence and death, then, are what one might look for in Auden's poetry.

Births and Deaths

Births: Both Auden's parents came from large Victorian families: "Father and Mother each was one of seven, | Though one died young and one was not all there." In fact, although Auden got the number of children in both his mother's and his father's generation wrong: Dr. Auden was one of the seventh of eight children; Mrs. Auden was the final child of eight. (Mrs. Auden's mother came from a family of nine.) You could explain the minor slip by saying that Auden used "seven" because he needed a rhyme for "Heaven".

[Family dramas: Every family has them. Here, John Auden (1758-1834) and Phoebe Woodhouse (1758-1828) were married on 14 March 1782, and their son, John Auden (1782-1836), was born 7 months and 28 days later on 11 Nov. 1782.]

Deaths: But instead of thinking that Auden had needed a rhyme for "Heaven", when he wrote of his father's family being one of "seven" children (not eight), one could wonder whether an apotropaic lapse was involved at the point when he mentioned that "one" child "died young" in his father's family. Dr. Auden's father, Rev. John Auden, died in 1876 when Dr. Auden was four. Then, two years later, Dr. Auden's older brother, William Hopkins Auden (or, curiously enough, W. H. Auden), died at Horninglow at the age of 15 in 1878. At the time Dr. Auden was a six year-old living in the same house in which his brother died suddenly of scarlet fever. (The "one" who was not all there on his father's side was Frederick Lewis Auden (1871-1948) and on his mother's side Margaret Bicknell (b. 1866).)

Mrs. Auden also suffered the loss of a brother while she was still young. Arthur Bicknell was killed in a railway accident at the age of 20 when his sister Constance was 12. But, as "Family Ghosts", confirms two different cultures embodied in the early experiences of Auden's parents: one culture essentially of life and one of death. The two Auden family deaths I have mentioned, those of the Rev. John Auden in 1876 and of William Auden in 1878, were the only ones which George Auden had to confront before a new family generation came into being with the birth of his own first child, George Bernard Auden (always known in the family as "Bernard"), in 1900.

Born on 27 August 1872, George A. Auden was, as I mentioned, one of eight siblings (seven brothers and one sister), he had three uncles and four aunts. Before the arrival of Bernard Auden in York on 5 July 1900, within his immediate family circle "only" Dr. Auden's father and one brother had died — that is, there were two deaths amongst his relatives out of a possible 14 (an 86% survival rate). By stark contrast, Constance Rosalie Bicknell, born on 13 February 1869, was one of five sisters and three brothers; she and her siblings had nine uncles and five aunts. Only a few months after baptizing his own youngest daughter at Southwold Church, Suffolk, Rev. Richard Bicknell died at Christmas in 1869. In the subsequent years, the toll of Bicknells and Birches amongst Constance Bicknell's closest relatives is a sombre and long-lasting one. On 30 January 1880: her mother, S. A. Birch, dies; on 26 February 1881: her brother, A. H. Bicknell is killed; ca. 1884: her aunt, E. E. Birch, dies; on 29 June 1884: her uncle, H. M. Birch, dies; on 28 March 1892: her favourite aunt, G. Bicknell, dies; on 5 July 1893: her favourite uncle, Charles Bicknell, dies; ca. 1896: her aunt, L. R. Birch, dies; in 1897: her uncle, J. W. Birch, dies; on 27 July 1898: her uncle, A. F. Birch, dies; ca. 1900: her aunt, L. Birch, dies.

Thus, her father and mother as well as one brother, four uncles and four aunts had died before 5 July 1900 when her and Dr. Auden's first child was born — 11 deaths out of a two-generation family circle of 21 (a survival rate for her Bicknell and Birch relatives of only 48%). By the time Constance Auden became a mother, she had experienced very much more close-at-hand death and suffering, very much more "abandonment", than her husband had.

Against the tragic reality of numerous infant deaths recorded in "Family Ghosts", there is the lone counter-point of just a single figure who survived past 100 years. The person with the greatest longevity in the database is the Rev. William Henry Roberts Longhurst (a distant relation of Auden's grandmother Selina Acton Birch), who was born in September 1838 and who died in September 1943 just short of his 105th birthday.

Religion: Anglicans

It is a commonplace (deriving from Auden's own remarks) to associate his ancestral history with the Church of England. "Family Ghosts" shows that this is a time-limited truth. It is correct to say that the 19th century shows a true swarm of clergymen in Auden's family: in the immediate context he had two clerical uncles: the Rev. John E. Auden (1860-1946) and the Rev. Alfred Auden (1865-1944); both grandfathers, the Rev. John Auden (1831-1876) and the Rev. Richard Bicknell (1823-1869); a great grandfather, the Rev. Henry W. Birch (1794-1854); and four granduncles: the Rev. Henry M. Birch (1820-1884), the Rev. Augustus Birch (1827-1898), the Rev. William Auden (1834-1904), and the Rev. Thomas Auden (1836-1920).

But this ecclesiastical moment was relatively short-lived. The Audens, Bicknells and Birches had not been especially strongly associated with the Church of England before the 19th century. And in the 20th century Auden's relations virtually gave up the church as a profession. Only two first cousins once removed, the Rev. Eustace Auden (1872-1958), and the Rev. Walter Auden (1874-1956) continued the 19th century tradition into the 20th century. Instead the males amongst the Audens, Bicknell and Birches moved into, or consolidated themselves in, the great (secular) institutions of the 20th century: medicine, science, law, the military, commerce. They became worshippers rather than celebrants, looking back, in some instances (such as that of Mrs. Auden) nostalgically, to the religious world into which they had once been more personally integrated. John Auden wrote, "The Bicknell aunts and uncle had apartments in Brooke Street in London, and the Anglo-Catholic ritual of nearby St Alban's, Holborn, was the High Church standard against which the Auden brothers measured other churches."

Religion: Quakers

If Auden's ancestral connection with the Church of England has been overstated, it is fair to say that his family's connection with another branch of Christianity has so far received far too little attention, and that is because it has until now been largely occluded. As noted earlier, for the first time "Family Ghosts" supplies a complete list of Auden's direct relations back to his 16 great-great grandparents. The list newly reveals some very important cultural co-ordinates, showing that in the generation of his great-great grandparents there were Quakers on both his father's and his mother's side of the family. John and Elizabeth Harman, Auden's great great great grandparents on his mother's side married at the Society of Friends' Meeting House in Bristol. John Harman was a wealthy banker, and their daughter Elizabeth Harman (1765-1838) married another rich banker Daniel Mildred (1757-ca.1830), who was also probably a Quaker.

On a more modest scale, Auden's father's family also seems to have had Quakers in its history, though the evidence here is less clear. There was a small Quaker community in Lichfield, a town strongly associated with the sect, where Samuel Nicklin and Hannah Gosling married in 1786. (Boswell, who visited Johnson at Lichfield in 1776, wrote in his Life of Samuel Johnson that "I have always loved the simplicity of manners of Quakers; and I observed that many a man was a Quaker without knowing it.") Other Auden ancestors in the West Midlands may also have been Quakers. Thomas Higgott and Anne Stretton were married in 1802 in Church Broughton, and John Hopkins and Martha Higgott married in Rolleston in 1803, both towns very near Burton upon Trent where there was another Quaker community.

Such information about Auden's family roots will eventually play a part in re-evaluating Auden's sustained interest in Quakerism and his contacts with Quakers in the 1930s and 1940s (including his stint teaching in 1932-1935 and in 1937 at the Downs School, a Quaker foundation).

Reconsidered within the frame of Auden's ancestral connections with the Quakers, Auden seems to have been much more deeply affected by Quakerism than scholars have hitherto recognized. For example, he calls the Society of Friends "the one Protestant body which deserved to succeed" in "The Prolific and the Devourer" (1939) and he describes the technique of a Quaker meeting as "probably indispensable to the running of any kind of democratic organisation", though he also offers some mild criticism there of the Quaker overestimation of "the power of the group to cure the unintegrated individual" (Prose2 450). He also praises the "quaker's quiet concern | For the uncoercive law" in his "Epithalamion" (1939; English Auden 455); and in his important lecture "Vocation and Society", given at Swarthmore in 1943, Auden commented that "the social group which has, so far, both in its religious and its social life, [been] the most obviously democratic is precisely the one which has consciously based itself upon a belief in the Inner Light, the Society of Friends" (Auden Studies 3 22). The background of Quaker belief amongst Auden's own direct ancestors laid bare by "Family Ghosts" is obviously relevant to a reinterpretation of these consistently positive comments about Quakerism.

Poets

Auden told an interviewer at Swarthmore in 1943 that "He had an uncle who wrote a large book on sulfuric acid [Dr. Harold Allden Auden], and a cousin, living in Toronto, who writes Latin grammars [Prof. Henry William Auden, technically a cousin once removed], but outside of them no literary talent exists or existed in his family." Quite apart from aggressively ignoring his own father's extremely copious writings, this statement omits mention of the poets (albeit little-known figures) to whom Auden was in fact related. It is impossible to tell whether Auden simply did not know about these links or whether he wanted to project himself the sole poet to have emerged from his family.

However, it actually seems that Auden had familial links to at least four minor poets: Thomas Vaux (1509-1556), James Woodhouse (1735-1820), John Laurens Bicknell (1746-1787) and Maria Riddell (1772-1808). More distantly, he was also a lineal descendant of Sir John Bourchier, the second Baron Berners, who translated Froissart's Chronicles in 1523-25 at Henry VIII's behest, and through marriage a relation of the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine. (In 1820 Lamartine married Marianne Eliza Birch (1795-1863), the cousin of Auden's great grandfather, the Rev. Henry Birch.)

• Thomas Vaux: On 30 April 1958, Dorothy Charlton (b. 1919) married W. H. Auden's first cousin once removed, Digby Auden (b. 1927). Ms Charlton's ancestry is impressive. The Tudor courtier and poet Thomas Vaux (1509-56), the Second Baron of Harrowden, was Ms Charlton's twelfth great grandfather. Thus by links through a cousin's marriage in the late 1950s, W. H. Auden became extremely distantly connected to the minor Tudor poet Thomas Vaux. Examples of Vaux's work, amongst them the poem which opens with the line "I loathe that I did love", were included in the book now usually known as Tottel's Miscellany (1557). In Hamlet the Grave-digger misquotes Vaux's poem. Thus, speaking in a very elastic spirit, it is (technically) true to claim that one of Auden's distant relations (but not ancestors) is cited by Shakespeare. Moreover, Ms Charlton's ninth great granduncle, Edward Vaux (1588-1661), the Fourth Baron of Harrowden, is widely supposed to have had two illegitimate sons (Nicholas and Henry Knollys) with Elizabeth Howard (1586-1658), the Countess of Banbury. Elizabeth Howard was the great-granddaughter of Henry Howard (1517-1547), Earl of Surrey, and one of the greatest poets of the Tudor court. Thus — again speaking in an unmoralistic and adventurously genealogical spirit — one can say that W. H. Auden had a family connection, albeit an even more tenuous one than is the case with the Vaux link, with Henry Howard.

• James Woodhouse: Auden was the first cousin four times removed of another poet (also mentioned above), James Woodhouse (1735-1820) of Rowley Regis. Woodhouse's parents lived on a small farm outside the village; his education finished at the age of seven and he became apprenticed as a cordwainer. He married Hannah Fletcher ("Daphne" in his poetry) in Rowley Regis in 1760. Woodhouse can be located within the 17th and 18th century's vogue for what Southey condescendingly labelled "Uneducated Poets". Thus, just as there was John Taylor, the "Water Poet", Ann Yearsley, the "Milkwoman of Clifton", and Stephen Duck, the "Thresher Poet", so Auden's relation Woodhouse was known as the "Shoemaker Poet".

Southey was dismissive of the Shoemaker Poet's talent. He wrote that Woodhouse was "a village shoemaker, and though he had been taken from school at seven years old, had so far improved the little which he could possibly have learnt there, as to eke out his scanty means by teaching to read and write."

Early in life Woodhouse was patronized (in every sense) by William Shenstone, who lived on an estate, "The Leasowes", nearby Rowley Regis. He also enjoyed important but compromising support from various other society figures including Lord Lytton and Edward Montagu. Robert Dodsley, the poet, bookseller and publisher (of Pope, Johnson and Gray), issued Woodhouse's first collection by subscription, Poems on Sundry Occasions (1764).

In the Epigraph to his Crispianus Scriblerus work Woodhouse described himself as: "Peter's the People's bard… Unpension'd Poet-Laureat, of the Poor." And he remarked that "Dr. Johnson's curiosity was excited by what was said of me in the literary world as a kind of wild beast from the country, and expressed a wish to Mr. Murphy, who was his intimate friend, to see me." It was thus that "Woodhouse became then a figure in the London literary world; he dined with Samuel Johnson at Mrs. Thrale's table, and incurred the doctor's famous advice to 'give nights and days, sir, to the study of Addison'" (Johnsonian Miscellanies, 1.233: this comes from an account in Blackwood's Magazine, Nov. 1829, of an interview between Johnson and Woodhouse). But behind Woodhouse's back, Dr. Johnson, remarked of him: "he may make an excellent shoemaker, but he can never make a good poet".

In the British Critic of August 1803, the passage in James Woodhouse's verse praised as best is this Crabbe-like passage from "Norbury Park, A Poem: Inscribed to W. LOCK, Esq.":

Among the various tints of tenderest green,

The clustering clumps, and tufted banks, between,

Thro' intersected fields, and flowery meads,

The white-wav'd Mole its mazey current leads,

And throws, thro' lucid breaks, the solar beam,

In dazzling glimpses from the glittering stream.

By this enchanted spot the burrowing wave

Probes thro' the spongey soil a temporal grave;

But soon emerges from the shades of night,

Cleans'd of its filth, reflecting clearer light:

So, when Man's Spirit quits its coil of clay,

His Body leaves, a time, the realms of day,

But soon from dust and darkness will return,

And, purg'd from dross, with brighter glories burn —

Unless that Body, clogg'd with impious crimes,

Sinks down to darker, and to drearier, climes,

With Spirit deeper plung'd from Earth and Skies,

To scenes of Light, and Love — no more to rise! (lines 414-31)

In later life Woodhouse was an increasingly evangelical Methodist and found himself, in his own words, "'growing grey in servitude, and poorer under patronage" (cited in Life and Poetical Works, 2.139). Having quarrelled for the final time in 1788 with the aristocratic Montagu family, he opened a bookshop in Grosvenor Square, London, with the support of James Dodsley. "A new Poems on Several Occasions appeared that year, and Woodhouse wrote both Norbury Park and Love Letters to my Wife in Verse in 1789, though neither was published until 1803 and 1804 respectively. Throughout the 1790s Woodhouse was at work on his autobiographical 'novel in verse', The Life and Lucubrations of Crispinus Scriblerus." He persevered with his writing and "According to his grandson Woodhouse gave up the bookselling business 'some time before his death', which 'was hastened by being knocked down by the pole of a carriage whilst crossing Orchard and Oxford Streets'.… He died of the injuries he sustained from the accident, in February 1820 at his home in Euston Square."

Southey, the Poet Laureate, wrote an epitaphic dismissal of Auden's ancestor, asserting that Woodhouse's patrons had "the satisfaction of knowing" that "if the talents which they brought into notice were not of a kind in either case [Woodhouse's or Stephen Duck's] to produce, under cultivation, extra-ordinary fruits, in both a deserving man was raised from poverty, and placed in circumstances favourable to his moral and intellectual nature."

• Auden's second great granduncle on his mother's side of the family, John Laurens Bicknell (1746-87), was a somewhat dissolute though ultimately successful barrister, who also had a significant achievement in poetry. John Bicknell was a friend of Thomas Day (1748-1789), the author, poet and political campaigner. Bicknell was described by Andrew Kippis in 1793 as Day's "closest and most intimate friend." Day and Bicknell may well have been at Charterhouse at the same time, and then later they roomed together as young lawyers in London.

Bicknell, like Day, was a member of the "Lunar Society of Birmingham" (active from around 1756 to 1800), headed by Erasmus Darwin. One commentator describes this Society as a famous "free-thinking group of manufacturers and natural philosophers, situated in England's Midlands, who were the most important scientific and entrepreneurial force outside London. Founded on a fierce interest in experimentation and invention and composed primarily of Fellows of the Royal Society, the group embraced core members and visiting associates alike. Core members included Soho Works founder Matthew Boulton (1728-1809), Scottish inventor James Watt (1736-1819), Unitarian minister and chemist Joseph Priestley (1733-1804), physician and philosophical tour de force Erasmus Darwin (1731-1802), Scottish physician and naturalist William Small (1734-75), engineer and educator Richard Lovell Edgeworth (1744-1817), poet and children's author Thomas Day (1748-89), Scottish chemist James Keir (1735-1820), clockmaker and founder of modern geology John Whitehurst (1713-88), physician Jonathan Stokes (1755-1831), minister Robert Augustus Johnson (1745-99), Quaker arms manufacturer Samuel Galton (1753-1832), and physician and botanist William Withering (1741-99). These regulars often entertained guests such as master ceramics designer and manufacturer Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95), botanist Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1830), and many others." (Sandra J. Burr, "Inspiring Lunatics: Biographical Portraits of the Lunar Society's Erasmus Darwin, Thomas Day, and Joseph Priestley", Eighteenth-Century Life (2000).) Bicknell's membership in the Lunar Society is a perfect example of the way in which ancestors of Mrs. Auden so regularly mixed in advanced intellectual and artistic circles.

Day and Bicknell were rationalists and free-thinkers. And also egotists. In 1769 they visited the Foundling Hospital for Girls in Shrewsbury and picked out a 12 year-old orphan whom Day determined to make into the "perfect" wife for himself. He called her "Sabrina Sidney", after "Sabrina", the poetical name for the river Severn, whose story is told in Comus, and "Sidney" from the name of his hero, Algernon Sidney. (Algernon Sidney (1623-83), was a political theorist, libertarian, republican and enemy of Charles II. The King had him executed in 1683 but he was exonerated after the Glorious Revolution of 1688.) Later in the year Day also procured a partner for Sabrina, whom he named Lucretia, from the Foundling Hospital in London. Lucretia was soon deemed to be the less intelligent of the pair and was apprenticed off with a dowry to a milliner in Ludgate Hill. (Details of this episode in Bicknell's life are taken here mainly from George Warren Gignilliat, Jr., The Author of Sandford and Merton: A Life of Thomas Day, Esq. (1932) and from Peter Rowland, The Life and Times of Thomas Day, 1748-1789: English Philanthropist and Author: Virtue Almost Personified (1996).)

Settling Sabrina in Lichfield (which in 1770 "could almost lay claim to being the true cultural centre of England"), Day conducted a number of experiments purportedly designed to continue the future Mrs. Day's education and to gauge her equanimity in the face of hazard and pain. Weirdly, he fired a pistol containing blanks at her petticoat and dripped sealing wax onto her bare forearm. Her fear of horses deeply disturbed him, though, and they parted company (with an annuity) in 1774.

Meanwhile, his friend Bicknell had "frittered his life away to some extent, dabbling in various short-lived literary enterprises, enjoying the delights of wine, women and song and allowing his legal practice into decline and disrepute." Another commentator writes that Bicknell "read and wrote poetry, but neglected to prepare briefs" and was "rather a literary dilettante, but he was also a thoroughgoing Rousseauist and humanitarian". James Boswell met Bicknell in 1786, introduced by the poet Anna Seward, the "Swan of Lichfield".

His health already compromised, John Laurens Bicknell proposed to Sabrina after her relationship with Thomas Day collapsed. They eventually married in 1784 and he managed to pull his legal career together briefly before dying in 1787. Sabrina Bicknell afterwards became a housekeeper in Dr Charles Burney Jnr.'s house.

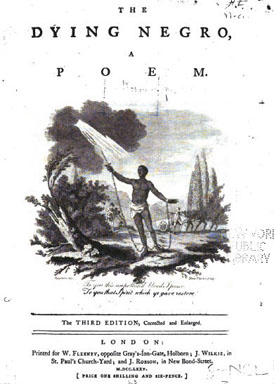

Under the pseudonym of "Joel Collier", John Laurens Bicknell had written the once-famous parody, Musical Travels through England by Joel Collier, Licenciate in Music, based on Charles Burney's peregrinations through Europe. However, though he died young, one more significant achievement remained to Bicknell's name. At about the time when Day's relationship with Sabrina Sidney was collapsing, Day and Bicknell had created together a very successful anti-slavery poem, The Dying Negro (1773), dedicated (from the enlarged, third edition. of 1774 onwards) to Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The lengthy title and subtitle of the first edition ran: The Dying Negro: A Poetical Epistle: Supposed to be Written by a Black, (Who Lately Shot Himself On Board a Vessel in the River Thames), to His Intended Wife, and the book was "one of the best-sellers of 1773" (the same year that Phyllis Wheatley published her Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral).

Bicknell, who composed most of the first version of the poem, provided 161 lines of the 307 of the original version, while Day penned only 146. (The definitive text of 1775 has 437 lines, 177 from Bicknell and 260 from Day, writes Peter Rowland, a Day scholar.) One scholar notes that, poignantly, "the lines which most strongly attack pride or most feelingly express disappointed love, were written, not by the Rousseauistic Day, but by Bicknell."

Title page of the 3rd edition of Thomas Day and John Bicknell, The Dying Negro

The Dying Negro is a poem composed in response to the Mansfield decision of 1772, in which the Chief Justice Lord Mansfield declared that "no slave could be forcibly removed from Britain and sold into slavery." The literary historian Brycchan Carey calls Bicknell and Day's 1773 poem "arguably [the work which] opened the poetic campaign against slavery." It is the "earliest unambiguously abolitionist poem" and deploys "unmistakably, if problematically, the rhetoric of sensibility" to make its point. The poem was based on actual events which had been reported in some London papers about a runaway slave, who while held, not on the "soil of England" but in a ship on the Thames, shot himself in the head rather than be separated from his beloved. (See, for example, The Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, 28 May 1773; cited in Carey's British Abolitionism and the Rhetoric of Sensibility: Writing, Sentiment, and Slavery, 1760–1807 (2005).) The poem is a "suicide note in verse in which the slave gives vent to his feelings at being torn from the country in which he now wishes to stay."

Maria Edgeworth, who knew Bicknell and Day, wrote in 1819 that the poem would "last as long as manly and benevolent hearts exist in England."

• Maria Riddell: The daughter of William Woodley, MP, the twice Governor of the Leeward Islands in the West Indies, Maria Woodley (as she then was), was writing poetry as early as the age of 15. She made trips to the Caribbean with her father, from one of which came her book Voyages to the Madeira and Leeward Caribbean Isles: with Sketches of the Natural History of these Islands (1792), and she wrote poems extolling the serenity of the Caribbean such as "Inscription written on an Hermitage in one of the Islands of the West Indies".

During a spell in the West Indies, in 1790 she married a plantation owner, Walter Riddell, and they subsequently moved to Scotland, where she established a kind of salon at her new home Woodley Park in Dumfriesshire. Through her Edinburgh publisher she was introduced to Robert Burns, with whom she had an extremely close though sometimes vexed friendship. Burns wrote several poems about her, including:

"Complimentary Epigram on Maria Riddell""Praise Woman still," his lordship roars,

"Deserv'd or not, no matter?"

But thee, whom all my soul adores,

Ev'n Flattery cannot flatter:Maria, all my thought and dream,

Inspires my vocal shell;

The more I praise my lovely theme,

The more the truth I tell.

Riddell was widowed in 1796 but she was still a figure of substances in the social-cum-literary worlds of Edinburgh and London. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, her only other "published work was The Metrical Miscellany (1802; 2nd edition, 1803), an anthology of fugitive verse by contemporary celebrities, in which she also published twenty of her own poems (among them the prefatory verses of 1802 by 'The Editor')."

The titles of some of these poems printed in The Metrical Miscellany, next to poems by figures such as Lord Palmerston and R. B. Sheridan, give a flavour of their simple lyrical style: "Elegy on the Death of Captain J. Woodley", "On a Red-Breast" and "Lines to a Friend who had Recommended the Precepts of the Stoic School to the Author's Adoption". And, as the latter shows, Riddell was part of the sentimentalist movement rejected the "frigid art" of neo-classical poise in favour of a warmer, more expressive and exquisite registration of the "joys and woes" of life:

Hence with the Stoic lore! whose frigid art

Would chill the gen'rous feelings of the soul,

Forbid kind Sympathy's responsive smart,

Or check the tear of rapture ere it roll.Still with its joys and woes, a changeful train!

Fair Sensibility be ever mine,

Th' alternate throb of pleasure and of pain,

And all that love and friendship can combine.

Slaves and Poetry

It is a provoking irony that John Laurens Bicknell should have been the co-author of one of the first major abolitionist poems, and that another of Audens ancestors on his mother's side should have been William Woodley, the father of Maria Riddell, since it means that there were slave-owners as well as abolitionists in the Auden family background.

William Woodley (1722-1793) was twice the governor general of the Leeward Islands in the mid and late 18th century. He was a slave-owner, being the owner of the vast "Profit" Plantation of St Christopher. He was also responsible for suppressing and slave rebellion on Montserrat in 1768, having seven ringleaders executed and imprisoning others. (Maria Riddell's uncle, Sir Ralph Payne, was another plantation owner and sole possessor of over 500 slaves.) Woodley's granddaughter, Isabella Corrance, was married to Rev. Augustus Frederick Birch, Auden's great uncle. Although it cannot be proved, the fact that other members of the family in Isabella Corrance's generation descending from William Woodley owned slaves suggests the likelihood that until slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, Isabella Corrance, the future wife of Auden's great uncle, may either have owned slaves or have received substantial money which was derived from slave ownership. Other members of the Woodley family owned slaves as well. Maria Riddell's brother, William Woodley [the second such named, who died in 1809] settled 172 slaves on St Kitts on his daughter Mary Woodley, for which she was awarded £2,925 4s 2d when slavery was abolished.

If Maria Riddell's father, brother, uncle and niece all owned slaves, as we know they did, it thus seems much more than likely that this poet of "sensibility" also owned slaves, settled on her by her parents or inherited from her husband. In addition, Riddell was married to Walter Riddell, a plantation owner on Antigua, who died in 1796, some 37 years before slavery was abolished in the British Empire. The salon of Woodley Park in Dumfriesshire, her glamorous friendships with the rich and famous, her patronage of Burns, her tender literary sentimentalism — all were underwritten, directly or indirectly, by the brutal regime of the slave-trade.

After such knowledge, what forgiveness? Think now

History has many cunning passages, contrived corridors

And issues, deceives with whispering ambitions,

Guides us by vanities.

The contemporary poet Derek Walcott was introduced to W. H. Auden's work by the poet and educator James Rodway on St. Lucia in the late 1940s. Rodway owned a collection of Faber books of poetry. "I remember, during that period, reading Auden with a tremendous amount of elation, a lot of excitement, and discovery," Walcott has recollected "I think Auden actually dared a lot more than either Pound or Eliot. I think his intellect was far more adventurous, far braver, far stronger, and far more reckless than either of them — plus, of course, there was also that tremendous intelligence behind the poetry." Echoes of Auden's work are everywhere in Walcott's early poetry. And when Walcott compiled and published his first book of poetry, 25 Poems in 1949, he indicated the iconic nature of these metropolitan publications and his own sense of relation to them. He "used a Faber volume of Auden as the typographical model.... He wanted a typeface that looked like one of the Faber volumes."

Whether or not Auden knew anything about the slaveowners in his distant background, revealed for the first time in "Family Ghosts", is impossible to say. Most likely, it was a subject which, if it was actually known about, was politely passed over in silence. But Auden recognized his own inevitable complicity as a white person with racial and imperial exploitation in "Whitsunday at Kirchstetten" (1962) when he wrote:

to most people

I'm the wrong color: it could be the looter's turn

for latrine-duty and the flogging-block,

my kin who trousered Africa, carried our smell

to germless poles.

(CP91 745)

Walcott too seems intuitively to have understood this deep moral ambiguity in Auden's past, an ambiguity for which Auden was not of course personally responsible but which he is wide-visioned enough to contemplate as part of his historical inheritance. Walcott echoes Auden's thought in "Whitsunday at Kirchstetten" when in the elegy which he wrote for Auden, he addressed him as "Master". Walcott plays on the dual nature of Auden's identity, both as a "Master" poet and as a member of the nation of colonial "Masters":

Once, past a wooden vestry,

down still colonial streets,

the hoisted chords of Wesley

were strong as miners' throats;in treachery and in union,

despite your Empire's wrong,

I made my first communion

there, with the English tongue.It was such dispossession

that made possession joy,

when, strict as Psalm or Lesson,

I learned your poetry.("Eulogy to W. H. Auden")

And Next?

As it now stands, "Family Ghosts" is only a beginning. It helps us in some instances to separate out Auden's personal mythology of his origins from the facts as we can know them. In other cases it helps us to provide detail supporting his statements about his background. But so much still remains to be done. In particular, new ways need to be found to illuminate the many other social and human linkages which provide the thick texture of culture as it is absorbed in childhood and adulthood alike. The website needs to find ways to shine a new kind of light onto professional and educational milieux, onto circles of association, onto friendships, onto all those vital bonds with other humans which cannot be subsumed within the web of family. For now, though, a beginning must be enough, enough simply to have raised this more than thousand-strong "family of ghosts".

February 2008

Note: This "Commentary" was written at the start of 2008 and reflects the state and size of the "Family Ghosts" website at that time. Since then, the database has grown extensively and become more intensively interwoven. Further discoveries will be covered in subsequent "Commentaries". But, in the meantime, readers may refer to the "Hotspots" page, which provides links to up-to-the-minute details on some of the better-known individuals in the genealogical tree.

© 2008 Nicholas Jenkins