Life can be

thought of as a sequence of experiences involving interactions between people

and objects. The interaction of vision, for example, is realized by the

reception and interpretation of energy packets (light) radiated by illuminated

matter. Similar interactions produce the sensory communications of speech,

hearing, and touch. These interactions can be two-way events. Humans and

animals can generate signals and movements that affect objects and other life.

However, humans alone build devices that extend in distance and in time our

ability to communicate and influence people and nature. For example,

telephones, libraries, and earth-moving equipment are a few of the machines and

systems we have constructed to extend our will to others and mold the

environment to suit our needs.

Interactions are facilitated

by interfaces. Interfaces can be either biological, such as ears and vocal

chords, or mechanical devices, such as loudspeakers and keyboards. Some -

vehicles, telescopes, television, and public address systems - extend our

natural abilities over great distances. Others - books, monuments, and

recording mechanisms - enable us to project our presence through time. Our

daily existence depends on the smooth operation of devices we take for granted.

How many of us would be able to survive without cars, televisions, telephones,

microwave ovens, computers, and information networks? These are just some of

the devices that able-bodied people interact with and rely on to get through an

average day.

|

|

Because

people with disabilities may have a diminished ability to use these interfaces,

they may experience difficulty in participating fully in daily life. In many

cases, however, the structure of our systems defines whether a person is able

or disabled. For example, if stairs were never invented, the inability to climb

stairs would not be a disability. Since society places the ability to

communicate in high regard, nonvocal or hearing-impaired individuals can

experience problems interacting with others.

Some people with disabilities

cannot produce normal "output" functions in terms of mobility and

production of communication for both person-to-person and person-to-machine

interactions; others have difficulty with the "input" sensory

functions of hearing and sight.

|

|

To cope with this problem, current devices (machines)

for people with disabilities enhance the interaction between the user (human)

and the environment (nature) and other people by providing either augmented or

alternate communication pathways. To perform mobility, communication, and daily

living tasks independently, individuals with severe disabilities must find

interface pathways to replace those that have been lost or amplify those that

are functional. High-level quadriplegics especially must overcome the

difficulty of replacing lost or diminished pathways to the outside world since

many of them can only control the muscles in their neck and above. The power to

promote user interface with a machine, translate sensor input into machine

activation, and produce a result that reflects on the environment is available

in many devices for people with disabilities.

Here are two examples of such

interfaces, drawn from my work at the Rehabilitation Research and Development

(RR&D) Center at the VA Medical Center in Palo Alto, CA.

Ultrasonic Head Control Unit

The Ultrasonic Head Control

Unit (UHCU) is an interface that allows quadriplegics to communicate their will

to the environment by enhancing their control over equipment such as

wheelchairs and specialized communication systems in a socially acceptable and

aesthetically pleasing manner.

|

The unit translates changing head positions into control

signals that operate devices to which it is attached. This design uses two

ultrasonic transducers. These transducers emit inaudible sound waves that

propagate through the air until reflected by an object. A portion of the echo

signal returns to the transmitting sensor and is detected by an electronic

circuit. The time from transmission of the ultrasound pulse to the reception of

the echo is proportional to the round-trip distance from the sensor to the

object. In the rehabilitation application, sensors are directed at the user's

head, from either the front or the rear, and on each side of the head. If the

user is in a wheelchair, the sensors are generally mounted on the back of the

wheel- chair. The sensors can also be mounted from the front. For example, if

the user is operating a computer, the sensors can be mounted on the

monitor.

The distance of each sensor to

the head and the fixed separation of the sensors describe an imaginary triangle

whose vertices are the two stationary sensors and the user's moving head. This

geometric relationship allows the offset of the apex (the head) from the

baseline and centerline of the two sensors to be calculated. The user's head

position can then be mapped onto a two-dimensional control space.

UHCU users merely tilt their

head off the vertical axis in the forward/backward or left/right directions.

Their changing head positions produce signals identical to those from a

proportional joystick. The UHCU can be thought of as a joystick substitute for

controlling an electric wheelchair, a communication aid, or a video

game.

Users of a modified electric

wheelchair equipped with a UHCU can navigate the chair by tilting their head

off the vertical axis. The changing head position is translated by the on-board

computer into speed and direction signals for the electric motors on the chair,

thus directing the motion of the chair. To travel forward, the user moves the

head forward of its normal, relaxed vertical position. Similar movements

perform the designed motion in the remaining three directions - left turn,

right turn, and backwards. This system accepts combinations and degrees of

these motions, so a smooth right turn can be accomplished by positioning the

head slightly forward and to the right. In effect, the user's head becomes a

substitute for the joystick control found on some electric wheelchairs.

Since the UHCU signals exactly

mimic those produced by a joystick, in wheelchair applications the UHCU can be

simply plugged into the motor controller. In this manner, no modifications to

the motor controller are necessary; the UHCU becomes an electronic module

providing head position control. Other devices that normally use a joystick or

switch closure as the human input mechanism can instead use an adapted

UHCU.

|

The main advantage of this

type of hardware interface is that no physical contact between the sensors and

the user's head is required. This effectively separates the user from the

device being controlled. Therefore, with this unit users should not feel

"wired-up" or confined by an apparatus around the face or body, as

frequently occurs with other interfaces. A UHCU implemented on an electric

wheelchair also has aesthetic advantages over other man/machine interfaces used

for this purpose. It seems to be more socially acceptable than alternative

designs.

In actual operation, the UHCU

wheelchair system performs satisfactorily. After about one hour of training and

practice, this system can be mastered by any individual who retains good head

position control. The head tilting required is so slight, only an inch or two,

that observers frequently cannot deduce the method of control. Since the UHCU

only responds to head tilts, the user can freely move the eyes or rotate the

head without affecting the navigation path. In this manner, the user can watch

for automobiles at intersections or converse with others while

traveling.

The UHCU is, for all practical

purposes, transparent to the operator, and the existence of any computer

hardware or software is not apparent. One "test pilot" commented that

the system was so high-tech that it appeared low-tech.

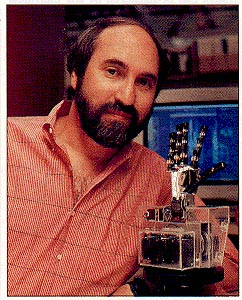

Dexter-II

Dexter-II is a

second-generation, computer-operated, electro-mechanical, fingerspelling hand.

It offers an improved solution to the communication problems that deaf/blind

people experience. This device translates incoming serial ASCII (a computer

code representing the letters and numbers) text into movements of a mechanical

hand. Dexter-II's finger movements are felt by the deaf/blind user and then

interpreted as the finger-spelling equivalents of the letters that comprise a

message. It enables a deaf/blind user to receive finger-spelled messages in

response to keyboard input during person-to-person communication, as well as

gain access to other sources of information.

This interface is designed to

allow deaf/blind users to independently receive information from a variety of

sources, including face-to-face conversation with people who do not know

finger-spelling, telephone communication, and computer access. The enhanced

communication capability will considerably improve the vocational and

recreational opportunities available to the deaf/blind community.

|

|

In operation, a message is typed on a keyboard by an

able-bodied person. Dexter-II's computer software matches each letter's ASCII

value with a memory array of stored control values. These data program

pulse-width modulation chips to operate its eight DC servo motors. Wire cables

anchored at the mechanical hand's fingertips and wound around pulleys serve as

the fingers' "tendons." As the motor shafts are energized, they turn

the pulleys, pull on the cables, and flex the fingers. These resultant

coordinated finger movements and hand positions are then felt by the deaf/blind

communicator and interpreted as letters of a message. Although the mechanical

hand cannot mimic the human hand in rotating the wrist to finger-spell a

"J," the fact that it always produces the same motions for a given

letter enhances its intelligibility.

Since it works with

electronically transmitted information, Dexter-II can be connected to a

computer, constituting an accessible "display." It can also be

operated over the telephone either from a remote computer or by a caller using

a telecommunication device for the deaf. When interfaced with a modified

decoder for the deaf, Dexter-II gives deaf/blind individuals the ability to

receive news, information, and entertainment from closed-caption television

programs.

Reactions to Dexter-II have

been enthusiastic, positive, and at times highly emotional. The increased

communication capability and ability to "talk" directly with people

other than interpreters are powerful motivations for using this interface. It

has the potential to provide deaf/blind users with untiring personal,

finger-spelling communication at rates approaching those of a human

interpreter.

The Human-Machine Integration

Section within RR&D is devoted to projects that help people with

disabilities convey their desires to their environment and facilitate

communication with others.

David L. Jaffe is a research

biomedical engineer at the Rehabilitation Research and Development Center at

the Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Palo Alto, CA

Veterans Affairs Health Care System

Rehabilitation Research and Development Center

3801 Miranda Ave, Mail Stop 153

Palo Alto, CA 94304

|