| |

| Research |

| Publications |

| Members |

| Material Requests |

| Directions |

| Research Interests |

|

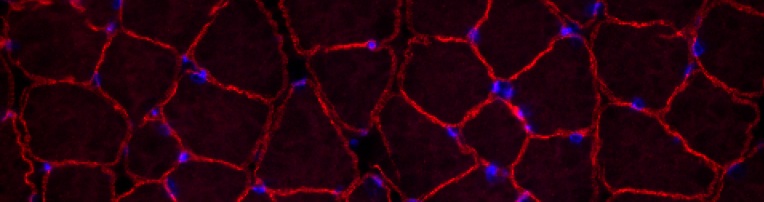

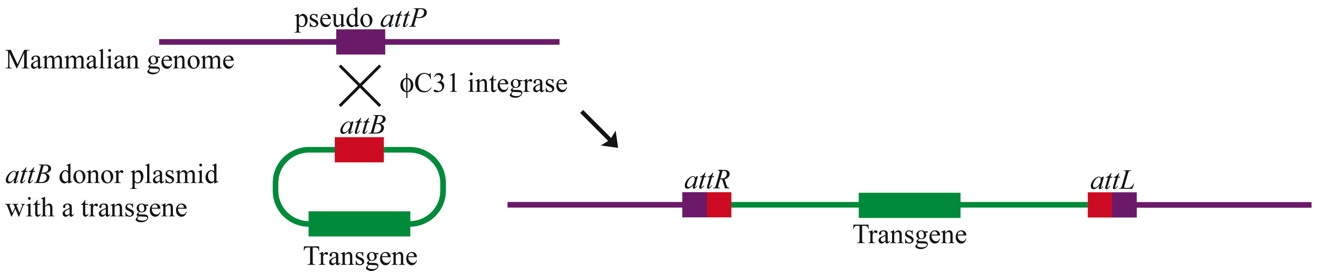

The Calos Lab is interested in developing novel gene and cell therapy approaches to address human diseases. Our primary approach is to use genetically-corrected stem cells as therapeutics, to develop strategies to treat genetic diseases like muscular dystrophy. The lab has expertise in methods for the genetic engineering of mammalian cells, including site-specific integrases, homologous recombination, and extrachromosomal vectors. Phage integrases for recombination in mammalian cells For example, we have developed the phiC31 integrase system for use in mammalian cells. This phage integrase pairs two short recognition sites, called attB and attP, and catalyzes recombination that results in chromosomal integration. This figure shows one approach we have developed with phiC31 integrase. We place an attB site on the plasmid that we wish to integrate into the chromosome. The enzyme finds a site similar to attP in the chromosome and carries out recombination. The net result is integration of the plasmid into the chromosome: |

We also utilize integrases with higher specificity, like Bxb1, that can recombine only at their own att sites. If the Bxb1 attP site is placed into the chromosomes, then Bxb1 integrase can be used to recombine a plasmid bearing the Bxb1 attB site into this location with high specificity. This short movie created by Alfonso Farruggio, a Genetics graduate student in the lab, illustrates how the reaction works: |

| |

Applications in Gene Therapy

We have developed approaches that cure hemophilia in disease model mice, by using hydrodynamic DNA injection and phiC31 integrase to bring about permanent integration of the factor VIII or IX genes in the liver:

These reviews summarize some of the recent work with phiC31 and other phage integrases:

Another important application of phage integrases is to create transgenic animals and plants. We pioneered this area by showing that phiC31 integrase could be used to target gene addition in Drosophila embryos at high efficiency and specificity. This method is now popular in the Drosophila community, and related strategies have been successful in many other organisms, as summarized in the following article:

iPSC strategies for regenerative medicine

An area of intense interest in the lab is the use of genetically-engineered induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) to develop therapeutics. For example, iPSC derived from patients with genetic diseases like muscular dystrophy can be corrected, differentiated, then engrafted back to the patient. We have used phiC31 integrase to add genes to reprogram adult cells into pluripotent stem cells:

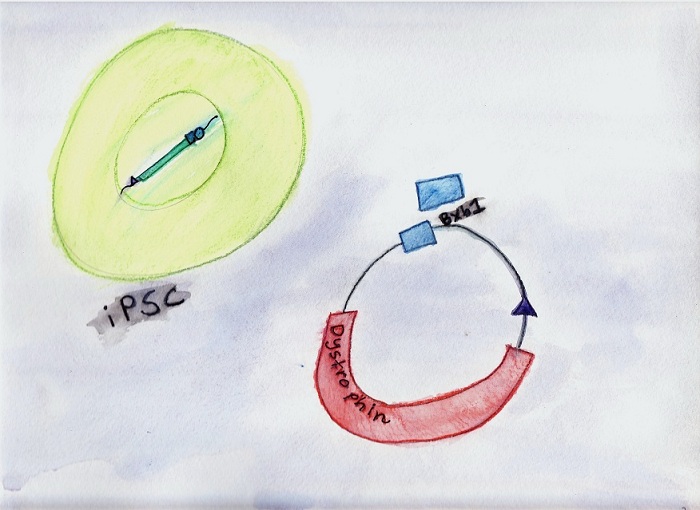

A current project involves

reprogramming fibroblasts from mdx mice, a disease model

for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and adding the

therapeutic dystrophin gene. Corrected cells are

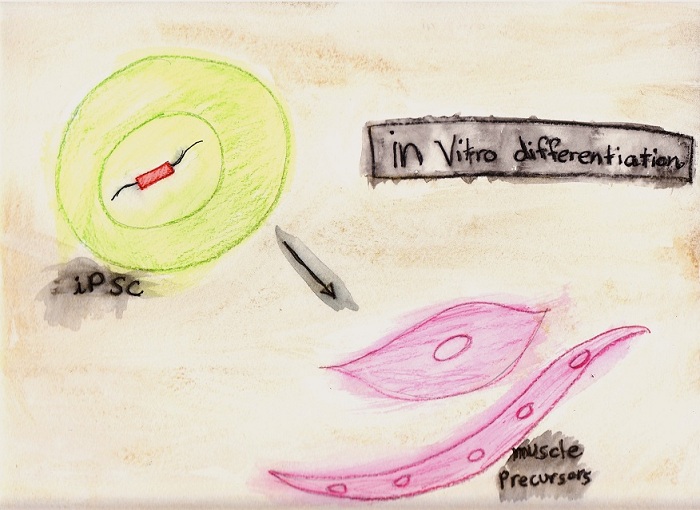

differentiated into muscle precursor cells in

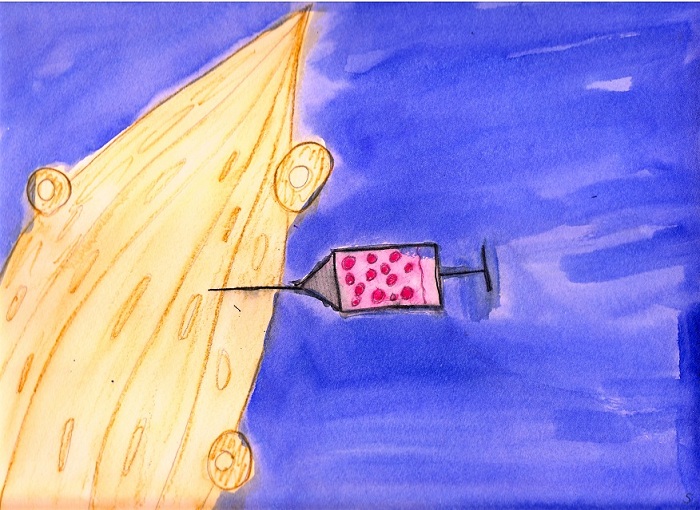

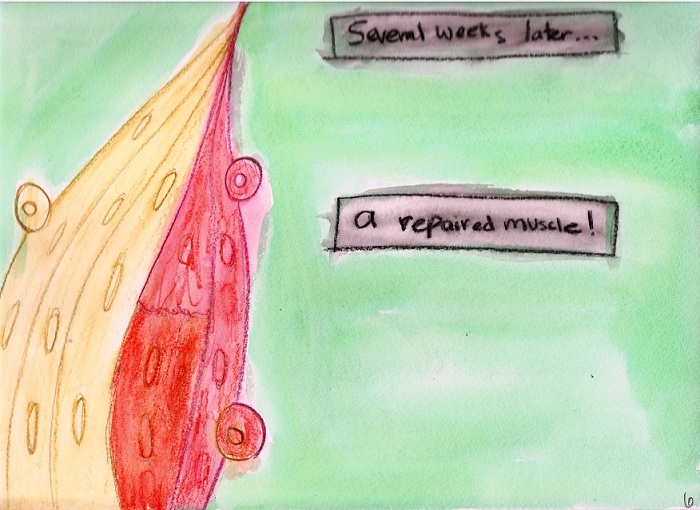

culture and are engrafted into mice to repair

muscle damage. This series of six images, created by Michele’s daughter Victoria, illustrates our first-generation system for reprogramming and gene correction:  1. Reprogramming.

2. Correction.

3. Excision of unwanted

sequences.

4.

In vitro differentiation.

6. Engraftment. |

Last updated on Feb 14th 2013