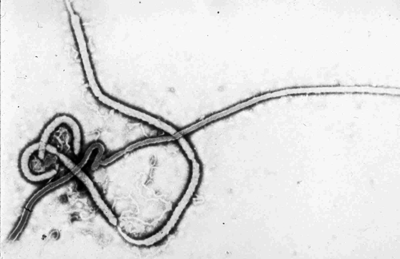

Ebola Virus

http://www.geocities.com/CapeCanaveral/Lab/5738/images/ebola2.gif

The Ebola virus is a member of the family filoviridae and the order mononegavirales and is the causative agent of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever (Ebola HF). Ebola is severe and often fatal among both humans and nonhuman primates with mortality rates reaching as high as 90% in some outbreaks.

Ebola virus was named for the river in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Zaire) in Africa where it was first recognized in 1976. Four strains of Ebola have since been identified: Ebola-Zaire, Ebola-Sudan, Ebola-Ivory Coast, and Ebola-Reston. All but Ebola-Reston are known to cause disease in humans.

To date, the origin and natural reservoir of Ebola virus is unknown, but it is believed to be zoonotic and maintained in a small animal (yet unidentified) that is native to Africa. As a result, it is unknown exactly how the virus spreads from animals to humans, but it is presumed to be by contact with an infected animal. Humans have also been infected from handling infected primates.

Ebola is transmitted between humans by direct contact with blood, saliva, and other excretions of an infected person and thus is easily spread to family, close contacts, and healthcare workers unless precautions are taken. In addition, nosocomial transmission (within a hospital) can also occur by the use of needles or other equipment contaminated by infected secretions. Fortunately, the ability to be transmitted via aerosols, while documented in the lab, has not been seen in real situations.

The incubation period of Ebola HF ranges from two to twenty-one days, after which symptoms such as fever, headache, joint and muscle aches, sore throat, and weakness abruptly appear. These symptoms are followed by diarrhea, vomiting, stomach pain, red eyes, rash, and impaired kidney and liver function. In some patients, this further progresses to internal and external bleeding.

It is initially difficult to diagnose Ebola clinically because many of the symptoms are nonspecific. However, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), or virus isolation can be used to diagnose Ebola HF in the lab.

Similar to other hemorrhagic fevers, there is no specific treatment or cure for Ebola HF, rather supportive care is given to patients to maintain their fluids, electrolytes, and blood pressure. Currently, there are no vaccines available to prevent Ebola infection; however, recent research has found a possible vaccine, which holds great potential for protection against both Ebola and Marburg viruses, and is currently undergoing further research and testing. Until a vaccine is licensed, the most effective means of prevention is containment, isolation of infected persons, and proper sterilization to prevent further spread and large outbreaks.

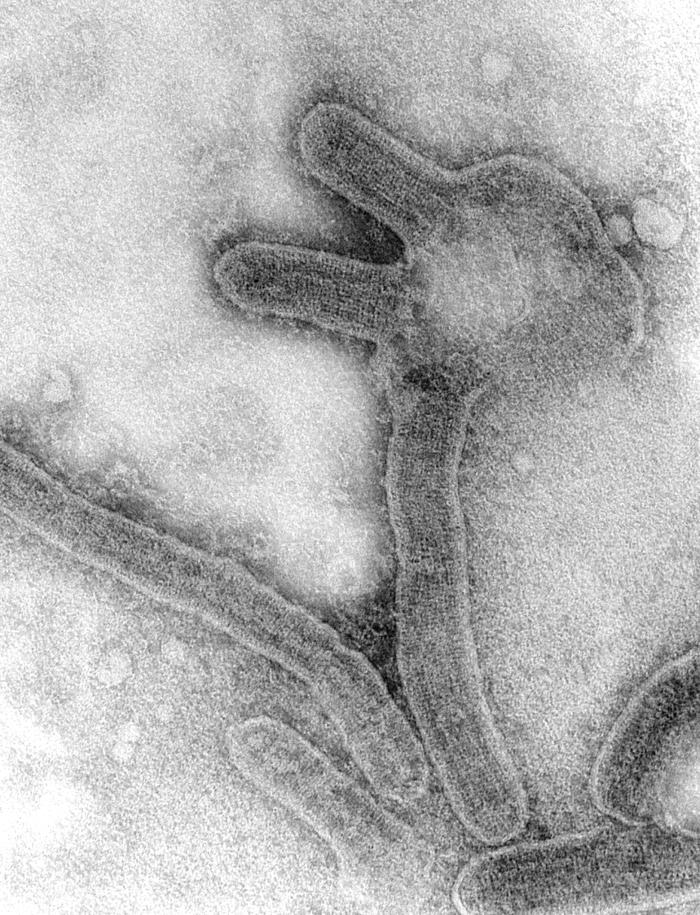

Marburg virus was the first virus of the Filoviridae family to be discovered. It is the causative agent of Marburg Hemorrhagic Fever, which is severe, highly fatal, affecting both humans and primates. It is similar to the Ebola virus, but produces different antigens.

The virus was first documented in the German town of Marburg, after which it was named. The outbreak involved 25 primary infections, with 7 deaths, and 6 secondary cases, with no deaths. Laboratory staff were infected when working directly with monkeys which had the Marburg virus. The secondary cases included two doctors, a nurse, a post-mortem attendant and the wife of a veterinarian. All had direct contact, usually involving blood, with a primary case.

The outbreak was traced to infected African grivets which were transported from Uganda to Germany for the development of polio vaccines. Subsequent cases and outbreaks occurred elsewhere in Germany, as well as in Yugoslavia, South Africa, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The most recent outbreak was in 2004-2005 in Angola, with possibly more than 300 fatal cases.

Marburg virus is spread through bodily fluid, including blood, saliva, urine, excrement, vomit, and other respiratory secretions. Transmission requires close contact between people. Casual contact through the aerosol spread of respiratory secretions does not appear to be sufficient in transmission.

Incubation period is 3 to 9 days, and transmission does not occur during this period.

Marburg hemorrhagic fever is characterized by a sudden onset of fever, headache and muscle pain. From there is rapidly progressing into debilitation. By day three, watery diarrhea, nausea and vomiting begin. Within one week a maculopapular rash may appear as well. The disease can then become increasingly damaging, causing jaundice, delirium, and organ failure. In severe and fatal cases, extensive hemorrhage occurs with spontaneous bleeding at venipuncutre sites. Patients generally die from hypovolemic shock as fluid leaks out of the blood vessels, causing blood pressure to drop.

As with other hemorrhagic fever viruses, there is currently no vaccine or effective treatment for Marburg. Hypotension and shock may require early administration of vasopressors and hemodynamic monitoring with attention to fluid and electrolyte balance, circulatory volume, and blood pressure. Patients tend to respond poorly to fluid infusions and rapidly develop pulmonary edema.

There are research groups working on the development of drugs and vaccines for Marburg, as well as Ebola. Both Genphar and Canada's National Microbiology Laboratory have developed vaccines that are undergoing further testing.