1994 Project Reports | Contents | Previous | Next | Home |

Development of Articulating Joints: the role of mechanical forces

Jean H Heegaard, PhD; Gary S Beaupré, PhD; Dennis R Carter, PhD

The structure and shape of bones and joints in the appendicular skeleton are determined by biological and mechanical factors. For more than a century, the idea that bones adapt to loads has been studied from the standpoint of bone remodeling, i.e., changes in the bone density that occur as a result of adaptation to mechanical stresses. Much less attention has been paid to the role of mechanical stimuli in influencing the shape of bones and joints beginning early in skeletal development, i.e., during morphogenesis.

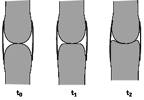

During morphogenesis, the future articulating joints first appear as divisions in the cartilaginous skeletal template. During this stage of development, the opposing joint surfaces are convex in shape. In many joints however, as development proceeds, one of the contacting surfaces progressively loses its convexity and eventually becomes concave, while the other surface remains convex (Figure 1). Understanding how such changes occur will provide new insights into the relative importance of biological (e.g., genetic) and mechanical (e.g., epigenetic) factors in skeletal development and adaptation.

Figure

1. Evolution of the shape of a diarthodial joint during early development Figure

1. Evolution of the shape of a diarthodial joint during early development

|

In the present study, a computer model is used to simulate bone growth and to study the influence of mechanical stimuli on the developing articulating joint. This model includes two opposing cartilaginous segments, both initially convex in shape. These segments are linked together through a pair of elastic members representing ligaments. Flexion-extension forces are applied to one of the segments through tendons, while the other segment is rigidly fixed. Flexion-extension forces are alternatively applied to the joint, causing the joint to articulate and giving rise to contact stresses at the joint surfaces (Figure 2). With this model isometric (i.e., shape-preserving) growth is modulated locally by the mechanical stimuli resulting from the flexion-extension process (Figure 3).

Available numerical methods for computing joint kinematics as a function of external applied loads fail to be effective when the joint geometries become complex, as is the case in human joints. Hence the current modeling approach is to decouple the problem into: 1) a rigid body analysis for the determination of the overall joint motion; and 2) a deformable body analysis for the determination of ligamentous forces and joint contact pressure. In the rigid body problem, equations are formulated within a Lagrangian framework by introducing adequate quasi-coordinates for expressing the contact conditions. The deformable body problem is solved, in turn, using standard finite element methods. Emphasis is put on obtaining objective constitutive relations for the cartilaginous segments and ligaments.

Preliminary results indicate that during flexion-extension, the contact region remains almost stationary on the movable (concave) joint segment, while the contact region on the fixed (convex) segment sweeps across a much larger area. Under the hypothesis that hydrostatic pressure will inhibit or retard growth, the concave-convex pattern can be understood as a result of locally controlled growth rates at the joint surface, with the concave segment having a lower growth rate than the convex segment.

Republished from the 1994 Rehabilitation R&D Center Progress Report. For

current information about this project, contact

Gary S Beaupré.