Overview

The Moler lab builds and operates tools for measuring magnetic fields on small length scales. We use these tools to study superconductivity and mesoscopic quantum mechanical effects at low temperatures.

Mesoscopic Magnetism Tool Box

|

|

|

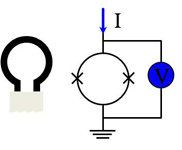

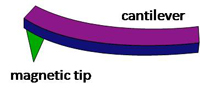

| SQUID | MFM | Hall Bar |

Research Projects & Highlights

Complex Oxides | |

We used scanning SQUID microscopy to investigate superconductivity and magnetism in exotic complex oxide systems.

We used scanning SQUID microscopy to investigate superconductivity and magnetism in exotic complex oxide systems.

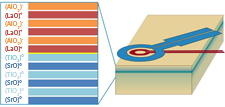

LAO/STO LaAlO3 and SrTiO3 are perovskite band insulators. After growing at least 4 unit cells of LAO on a STO substrate the polar/nonpolar interface between exhibits a number of interesting properties including a high mobility two dimensional conductivity, superconductivity below 100 mK, magnetism and an electric field controlled metal insulator and superconductor insulator transition. δ-doped SrTiO3 Doped STO is the lowest-density bulk superconductor that maintains a high-mobility. The thickness of the δ-doped layer can be precisely controlled and tune a transition from 2D to 3D superconductivity. Direct imaging of the coexistance of ferromagnetism and superconductivity at the LaAlO3/SrTiO3 interface Nature Physics (2011). News and Views in Nature Physics | |

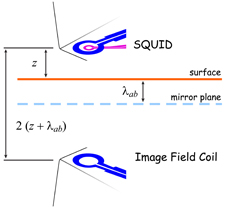

Local Measurement of Superconducting Penetration Depth | |

We can use our magnetic probes to measure the London penetration depth. This

is the distance over which superconductors expel magnetic fields, and

its chagne with temperatur can tell us about the superconducting state.

So it is one of the first things to be measured in new superconducting

materials. The twist is that our magnetic probes can measure the penetration

depth locally, so we can test the uniformity of the sample, which is

invisible to traditional techniques.

We can use our magnetic probes to measure the London penetration depth. This

is the distance over which superconductors expel magnetic fields, and

its chagne with temperatur can tell us about the superconducting state.

So it is one of the first things to be measured in new superconducting

materials. The twist is that our magnetic probes can measure the penetration

depth locally, so we can test the uniformity of the sample, which is

invisible to traditional techniques.

| |

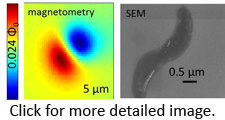

Magnetic imaging of individual magnetotactic bacteria | |

Biotechnology represent a new and exciting application of SQUID microscopy. Several biomedical applications, such as bio-separation, MRI and drug delivery use nanomagnets. The magnetic properties of nanomagnets are usually measured in large groups, which can be problematic due to the large dispersion of their properties. Magnetotactic bacteria are a group of bacteria that naturally grow magnetic particles, which magnetically align along a chain and result in alignment of the bacteria with earth's magnetic field (like a compass needle). We use scanning SQUID to detect magnetotactic bacteria and measure their moment properties and their response to small fields on an individual basis. We observe large dispersion in their magnetic properties.

Biotechnology represent a new and exciting application of SQUID microscopy. Several biomedical applications, such as bio-separation, MRI and drug delivery use nanomagnets. The magnetic properties of nanomagnets are usually measured in large groups, which can be problematic due to the large dispersion of their properties. Magnetotactic bacteria are a group of bacteria that naturally grow magnetic particles, which magnetically align along a chain and result in alignment of the bacteria with earth's magnetic field (like a compass needle). We use scanning SQUID to detect magnetotactic bacteria and measure their moment properties and their response to small fields on an individual basis. We observe large dispersion in their magnetic properties.

| |

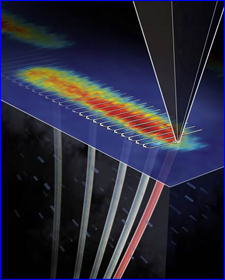

Next Generation SQUID Microscope | |

We are developing the next generation of SQUID sensors and incorporating them into a new user scanning SQUID microscopy user facility at Stanford. The SQUIDs, designed at Stanford and fabricated at IBM's Josephson line in Yorktown Heights, NY, will combine tenth micron lithography with device planarization to produce devices with deep sub-micron spatial resolution. In addition, we have designed and are building SQUID samplers, which will sense repetitive magnetic fields with a temporal resolution of as low as 10 psec, and dispersive SQUIDs, which will have (calculated) spin sensitivities of an electron spin in a 1 Hz bandwidth.

We are developing the next generation of SQUID sensors and incorporating them into a new user scanning SQUID microscopy user facility at Stanford. The SQUIDs, designed at Stanford and fabricated at IBM's Josephson line in Yorktown Heights, NY, will combine tenth micron lithography with device planarization to produce devices with deep sub-micron spatial resolution. In addition, we have designed and are building SQUID samplers, which will sense repetitive magnetic fields with a temporal resolution of as low as 10 psec, and dispersive SQUIDs, which will have (calculated) spin sensitivities of an electron spin in a 1 Hz bandwidth.

| |

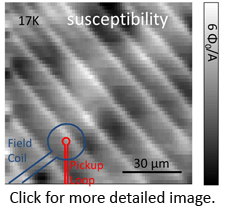

Modulated superfluid density in twinned high Tc superconductors | |

Several physical properties like the local strain, the bond angle, and the magnetic order may change on twin boundaries in orthorhombic crystals. These properties are known to affect superconductivity in bulk measurements. We use scanning SQUID to image the local magnetometry and susceptibility on the surface of twinned superconductors. We observe increased diamagnetic susceptibility in underdoped, but not overdoped, single crystals of the pnictide superconductor Ba(Fe1-xCox)2As2 , consistent with enhanced superfluid density on twin boundaries. Interesting information is also acquired by following the vortex behavior. Individual vortices avoid pinning on or crossing the twin boundaries, and prefer to travel parallel to them. These results help us connect the magnetic properties with the local changes in the crystal.

Several physical properties like the local strain, the bond angle, and the magnetic order may change on twin boundaries in orthorhombic crystals. These properties are known to affect superconductivity in bulk measurements. We use scanning SQUID to image the local magnetometry and susceptibility on the surface of twinned superconductors. We observe increased diamagnetic susceptibility in underdoped, but not overdoped, single crystals of the pnictide superconductor Ba(Fe1-xCox)2As2 , consistent with enhanced superfluid density on twin boundaries. Interesting information is also acquired by following the vortex behavior. Individual vortices avoid pinning on or crossing the twin boundaries, and prefer to travel parallel to them. These results help us connect the magnetic properties with the local changes in the crystal.Enhanced superfluid density on twin boundaries in Ba(Fe1-xCox)2As2 PRB (2010). Viewpoint in Physics | |

Vortex manipulation by MFM | |

Superconductors often contain quantized microscopic whirlpools of electrons, called vortices. Vortices are a diverse area of study for condensed matter because of the interplay between thermal fluctuations, vortex–vortex interactions and the interaction of the vortex core with the three-dimensional disorder landscape. We use magnetic force microscopy (MFM) to image and manipulate individual vortices in a detwinned YBa2Cu3O6.991 single crystal, directly measuring the interaction of a moving vortex with the local disorder potential. We find an unexpected and marked enhancement of the response of a vortex to pulling when we wiggle it transversely. In addition, we find enhanced vortex pinning anisotropy that suggests clustering of oxygen vacancies in our sample and demonstrates the power of MFM to probe vortex structure and microscopic defects that cause pinning.

Superconductors often contain quantized microscopic whirlpools of electrons, called vortices. Vortices are a diverse area of study for condensed matter because of the interplay between thermal fluctuations, vortex–vortex interactions and the interaction of the vortex core with the three-dimensional disorder landscape. We use magnetic force microscopy (MFM) to image and manipulate individual vortices in a detwinned YBa2Cu3O6.991 single crystal, directly measuring the interaction of a moving vortex with the local disorder potential. We find an unexpected and marked enhancement of the response of a vortex to pulling when we wiggle it transversely. In addition, we find enhanced vortex pinning anisotropy that suggests clustering of oxygen vacancies in our sample and demonstrates the power of MFM to probe vortex structure and microscopic defects that cause pinning.Mechanics of individual isolated vortices in a cuprate superconductor Nat. Phys. (2009). | |

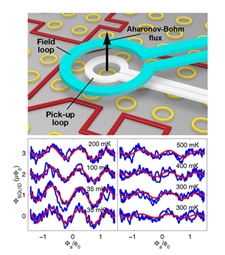

Persistent Currents | |

Many people are familiar with the lorentz current induced in normal metals by a time varying magnetic field or the persistent shielding currents generated by superconductors in an applied field. However, a surprising theoretical prediction suggests a persistent current can be supported in a normal metal ring even with finite resistance. Specifically in the presence of a magnetic field if electrons can travel around the ring without losing their phase coherence a current is expected equal to one electron traveling at the fermi velocity. Measuring these currents using transport techniques is challenging because attaching leads to the ring changes the coherence of the electrons. We used our scanning SQUID to detect the small magnetic moment generated by the currents flowing in these rings.

Many people are familiar with the lorentz current induced in normal metals by a time varying magnetic field or the persistent shielding currents generated by superconductors in an applied field. However, a surprising theoretical prediction suggests a persistent current can be supported in a normal metal ring even with finite resistance. Specifically in the presence of a magnetic field if electrons can travel around the ring without losing their phase coherence a current is expected equal to one electron traveling at the fermi velocity. Measuring these currents using transport techniques is challenging because attaching leads to the ring changes the coherence of the electrons. We used our scanning SQUID to detect the small magnetic moment generated by the currents flowing in these rings.Persistent Currents in Normal Metal Rings PRL (2009). Viewpoint in Physics | |