ORLAN: IS IT ART?

ORLAN AND THE TRANSGRESSIVE ACT

The French performance artist whose assumed name is Orlan has embarked on a campaign of self-transformation through plastic surgery. The photo-documentation of her operation/performances furnishes both the imagery and the financial support for her art. Below, the author grapples with the many issues raised by a body of work that gives new meaning to the term "cutting edge."

BY BARBARA ROSE

Art in America 81:2 (February 1993), pp. 83-125

Being a narcissist isn't easy when the question is not of loving your own image, but of recreating the self through deliberate acts of alienation.

--Orlan, L 'Acte pour L'Art

Do not misunderstand me too quickly.

--Barbara Rose

Orlan is not her name. Her face is not her face. Soon her body will not be her body. Paradox is her content; subversion is her technique. Her features and limbs are endlessly photographed and reproduced; in France, she appears in mass- media magazines and on television talk shows. Each time she is seen she looks different, because her performances take place in the operating room and involve plastic surgery. What we actually know about the video- and- performance artist who calls herself "Orlan" is less than what is known about Orlon, the synthetic fiber whose trade name closely resembles her chosen alias. This assumed name, moreover, will in turn be altered: when the total self-transformation she plans is complete, an advertising agency will select a new name consonant with her new image.

Throughout her career as a well- known French multimedia artist, Orlan has trafficked in notions of an ambiguous and constantly shifting identity. Her actions call into question whether our self- representations conform to an inner reality or whether they are actually carefully contrived falsehoods fabricated for marketing purposes--in the media or in society at large.

Orlan's journey from the art gallery to the operating room began in the late '60s in the streets of her home town of St. Etienne. As part of the radical activities triggered by the liberation movements of les evenements de mai 1968, she improvised her first performances and public spectacles. In the '70s she did performance pieces in Lyons and, later,outside the Guggenheim Museum in New York. These consisted of abstract measuring actions relating her body to a medieval convent and to a modern art museum. Her subsequent work then came to relate religious iconography to structures of the art world. She challenged both religious traditions and art- world assumptions, the former through blasphemous imagery, the latter with real time/real place actions identifying art with life.l

As a star in her own literal "theater of operation,". Orlan leaves her background deliberately fuzzy, the better to maintain the anonymity required to project an enigmatic "star quality." Here is what we know: she was born on May 30,1947, in the industrial town of St. Etienne. In 1980 she moved to Paris. Her studio is in the working- class suburb of Ivry- sur- Seine, next. door to the insane asylum where the original artiste maudit, Antonin Artaud, died. Like El Greco and Gericault, who used inmates as models, she recruited inmates to appear in her early tableaux vivants, such as her video- and- performance piece inspired by Caravaggesque stereotypes, St. Orlan and the Elders. Presently she earns a living as a professor of fine arts at the Ecole des Beaux- Arts in Dijon. She also sells images of her performances and her plastic surgery operations documented in films, videos and elaborate, staged photographs.

Like many artists of her generation both in France and in the U.S., Orlan was influenced by Duchamp. Her response was an extreme one: to consider her own body a "readymade." Through Ben Vautier, who showed her work in his famous Nice gallery where Yves Klein and so many other members of the French avant- garde got their start, she came into contact with members of Fluxus, and she continues to collaborate with Jean Dupuy. In 1971 she baptized herself "Saint Orlan," festooning her body with billowing draperies made of black vinyl or white leatherette. She exhibited these elaborate sculptural costumes in a show in Milan in 1972. Soon she began to wear her ever more exaggerated faux- Baroque costumes in staged tableaux vivants. High contrast color photographs of Saint Orlan, both living doll and living sculpture, were integrated into photo- collages, videos and films tracing a fictive hagiography.

Convinced that with its exaggerated emotionalism Bernini's St. Teresa in Ecstasy was the first postmodernist sculpture, Orlan found relationships between the forced pathos of Counter- Reformation esthetics and the historical references of contemporary artistic practice. The prototype image of Saint Orlan was a marble sculpture she carved and then, in the tradition of academic sculpture since the Renaissance, sent to be enlarged or "pointed up" to full scale. Her incarnation as Saint Orlan focused on the hypocrisy of the way society has traditionally split the female image into madonna and whore. She played off this long- entrenched dichotomy by exposing only one breast (as the nursing Virgin Mary is depicted), to differentiate Saint Orlan from a topless pinup. (The single exposed breast also referred to the Amazons of ancient mythology, represented as having only one breast to be free to sling warriors' quivers over exposed chests.)

In 1990, Orlan shed her saintly robes and decided to be "reincarnated" by altering her face and body through a series of carefully planned and documented operations. Her new medium would be her own flesh. The idea of turning surgical interventions into performance art occurred to her when she was operated on for an extra- uterine pregnancy under a local anesthetic which permitted her to play the role of detached observer as well as patient.

On her 43rd birthday, in 1990, Orlan had the first of the operation/performances that will totally transform her face and body. Thus far she has had five of the seven operations her project calls for. In her effort to represent an ideal formulated by male desire, she does not strive to improve or rejuvenate her original appearance (she has never had a face lift) but uses her body as a medium of transformation. The "sculpting" or carving up of her body sets up an intentional parallel between religious martyrdom and the contemporary suffering for beauty through plastic surgery that writers like Belgian feminist France Borel have identified as the rite of passage of our epoch.l

With self- transformation in mind, and proceeding with a cold, Cartesian logic buttressed by her considerable knowledge of esthetics and art history, Orlan began to deconstruct mythological images of women. Recalling that the ancient Greek artist Zeuxis made a practice of choosing the best parts from different models and combining them to produce the ideal woman, Orlan selected features from famous Renaissance and post- Renaissance representations of idealized feminine beauty. (Here one notes that the fetishization of body parts imposed on women by men since antiquity did not hold true for images of the masculine ideal. For male figures, ancient artists might improve on nature but the masculine ideal did not require fragmentation and recombination of the best parts of several models.)

Each of Orlan's operations is designed to alter a specific feature. Supplying surgeons with computer- generated images of the nose of a famous, unattributed School of Fontainebleau sculpture of Diana, the mouth of Boucher's Europa, the forehead of Leonardo's Mona Lisa, the chin of Botticelli's Venus and the eyes of Gerome's Pysche as guides to her transformation, Orlan also decorates the operating rooms with enlarged reproductions of the relevant details from these same works.2

But Orlan's female prototypes are also selected for reasons that go beyond the appearance of their "ideal" features--reasons involving history and mythology: she chose Diana because the goddess was an aggressive adventuress and did not submit to men; Psyche because of her need for love and spiritual beauty; Europa because she looked to another continent, permitting herself to be carried away into an unknown future. Venus is part of the Orlan myth because of her connection to fertility and creativity, and the Mona Lisa because of her androgyny--the legend being that the painting actually represents a man, perhaps Leonardo himself.

The operation/performances are choreographed and directed by the artist herself and involve music, poetry and dance. They are costumed, if possible, by a famous couturier. Paco Rabanne designed the vestments for the first operation. All the accoutrements, including crucifixes and plastic fruit and flowers, are sterilized in accordance with operatingroom standards, as are the photo blowups of preceding Orlan performances that decorate the operating room. Only state- certified surgeons operate.

To support her expensive and complex undertaking, Orlan earns money through the sale of the rights to her photos and videos and requires payment for interviews. The production, direction and casting of each operation become fodder for the photos, videotapes and films. As the French representative to the Sydney Biennial in December 1992, she included in the exhibition vials containing samples of her liquefied flesh and blood drained off during the "body- sculpting" part of the operations. These relics are also intended to be marketed to raise funds for the two remaining operations.

Orlan has a sense of humor, which led her to burlesque the selling of the artist rather than the art in an early work, Le Baiser de l'Artiste, 1977. Catherine Millet has described the scandal provoked when Orlan stationed herself outside the Grand Palais, site of FIAC, the French art fair, next to a life- size photo of her torso transformed into a slot machine that she identified as an automatic kiss- vending object. Customers who inserted five francs in the slot between the breasts could watch the coin descend to the crotch, at which point the live artist jumped off her pedestal to reward the purchaser with a real kiss. According to Millet, "this sexual union was like an X ray of the frenzy of exchange of contacts in the contemporary art world where the merchandising of the artist's personality replaces the merchandising of art."3

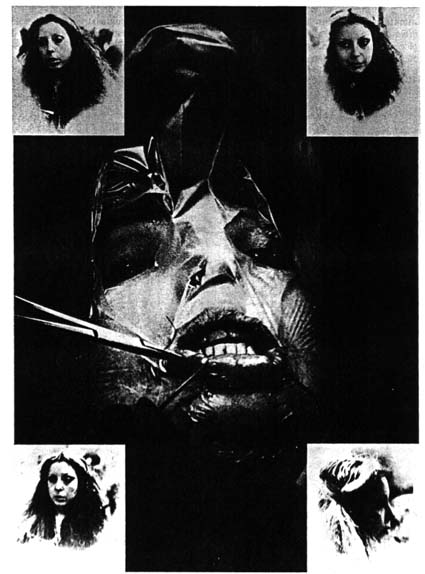

Official Portrait with a Bride of Frankenstein Wig, 1990 after the third operation , photograph mounted on aluminum, 59 by 39 inches. Photo Fabrice Leveque.

Orlan went to India to obtain enormous flashy billboards, of the type used to advertise popular Indian films. These have the highkitsch look of 1950s Hollywood posters. In addition to the artist herself, the billboards feature the surgeons and operating- room technicians, as well as supporting- cast actors and dancers. Not all the credits go to literal participants in the operating room: Pierre Restany, Achille Bonito Oliva and Hans Haacke, for example, get prominent billing because they have supported Orlan's work in the past.

In India, Orlan studied the Cult of Kali and gathered sacred texts describing the body as a sack or costume to be shed. She will read from these texts in her next operation/performance, which will transform her own fashionably retroussé nose into the long, pointed configuration favored by artists of the School of Fontainebleau. The African male striptease dancer who appeared in the first operation/ performance will be replaced in the next one by a classical Indian dancer.

Orlan asserts that art is a matter of life and death, and she isn't kidding: each time she is operated on, there is an increasing element of risk. She insists on being conscious to direct and choreograph the actions, so the operations take place under local rather than general anesthesia. The procedure, known as an epidural block, requires a spinal injection that risks paralyzing the patient if the needle does not hit its mark exactly. With each successive surgical intervention and injection, the danger is said to increase. Orlan may be playing Russian roulette by turning her body into an art work. To at least some degree she risks deformation, paralysis, even death. As the artist accepts mortality, she proposes, through the Kali references, a ritual interpretation of her actions as spiritual transcendence.

Orlan's work has many post- Duchampian precedents. By the time Body art became a full- fledged form of expression in America in the late 1960s, the element of risk had pretty well disappeared in more conventional forms of art. For Herbert Marcuse and his followers co- optation meant the death of art as a source of opposition to society. The enshrinement of the avant- garde in academia as well as its celebration in museums and international exhibitions exposed the romantic myth of the suffering artist, once but no longer marginal to society, as hardly relevant. Dennis Oppenheim, Chris Burden, Bruce Nauman, Vito Acconci and others responded to this challenge with actions and performances involving conceivable or actual danger and pain. The eventual integration of Body art into the art market put an end to the effectiveness of their strategies. The bourgeois art audience proved to have as much of an appetite for Xrated Body art as for Pop sensationalism.

Orlan calls her work Carnal art to distinguish it from Body art, although she acknowledges common sources. As we have noted, the background of her work includes movie- poster images and reflects the cult of personality introduced into the art world by Duchamp and brought to full flowering by Warhol and Beuys. Duchamp's coy Rrose Sélavy directly inspired Orlan to imply that the beauty business is just another drag act. Warhol's twisted dandyism and his insistence that surface appearance is all that matters is certainly part of her history. More important, however, is Beuys's adoption of the role of a shaman whose wounds represent the sickness of society as a whole. By turning herself into a receiving set for signals sent by men to women for millennia, she absorbs and acts out the madness of a demand for an unachievable physical perfection.

Orlan acknowledges a specific debt to Herman Nitsch and the Viennese "Aktionismus" group that developed in the '60s--artists who startled spectators with their ritualistic staged imitations of blood sacrifices. Of all the Viennese artists, she is perhaps closest to Rudolf Schwarzkogler, who had himself photographed (supposedly) slicing off pieces of his penis as if it were so much salami.

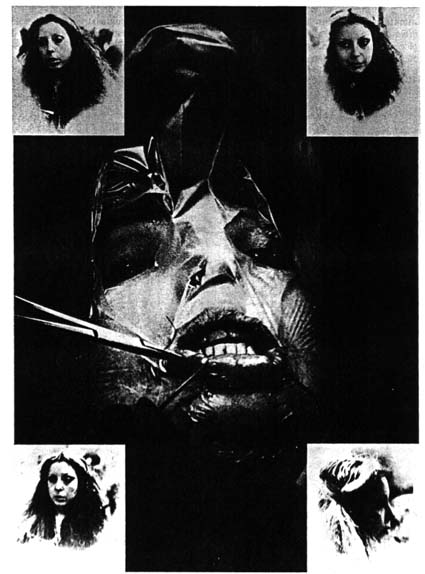

A Mouth for Grapes, photograph mounted on aluminum, 20 by 31 1/2 inches, from the fourth operation/performance, "he Mouth of Europa and ihe Figure of Venus." Photo Joel Nicolas.

'A little while longer and you will see me no more. . . a little while longer and . . . you will see me . . . ," four video projections of images from "The Mouth of Europa and the Figure of Venus," accompanied by a text quoting the words of Christ before the Passion; at the 1992 Sydney Biennial. Photo Stephan Auirach.

However, there is a crucial difference between the Viennese actions and Orlan's peformances: with them as with many examples of Body art, there was an element of theatrical fakery. The barnyard and the abattoir, not the operating room, provided blood for the Viennese performance artists. "Documentary" photographs were frequently staged: Schwarzkogler did not bleed to death any more than Schwarzenegger's on-screen blood is real. (Nor did Yves Klein jump out a window.)

The methodical examination of the relationship between the fake and the real is the center point around which Orlan's deliberately "questionable" art revolves.4 I call it art because after considerable reflection I do believe that Orlan is a genuine artist, dead serious in her intent and fully aware of the risks and consequences of her elaborately calculated actions. In the end, the two essential criteria for distinguishing art from nonart, intentionality and transformation, are present in all her efforts. The photographs, videos and posters that are the residue of her performances are composed, structured and highly self- conscious. To conclude that Orlan's taboochallenging investigations are esthetic actions rather than pathological behavior forces us to reconsider the boundary that separates "normality" from madness,5 as well as the line that separates art from nonart. Indeed such an examination of the limits of art is a criical objective of her confrontational actions.6

Orlan's brutal, blunt and sometimes gory imagery flatters neither herself nor the public; it transmits disquieting and alarming signals of profound psychological and social disorder that nobody in his or her right mind wants around the house. Her program also provides a devastating critique of the psychological and physical consequences of the distortions of nature implied in the advanced technologies discovered by scientific research, from microsurgery to organ transplants to potential genetic engineering.7

Orlan's insistence that art is a life- or- death issue involving literal as well as metaphoric risk continues to raise the question of whether she is inspired or crazy. Her focus on the fine line separating the committed artist from the "committed" lunatic is a direct challenge to the ease of integration of much so- called critical art. She actively asserts the necessity of marginality and danger. The extremity of her stance causes one to wonder if going on stage and smearing chocolate on one's nude body may be a cop- out for both artist and voyeur.

Orlan's performances might be read as rituals of female submission, analogous to primitive rites involving the cutting up of women's bodies. But actually she aims to exorcise society's program to deprive women of aggressive instincts of any kind. During the process of planning, enacting and documenting the surgical steps of her transformation, Orlan remains in control of her own destiny. If the parts of seven different ideal women are needed to fulfill Adam's desire for an Eve made in his image, Orlan consciously chooses to undergo the necessary mutilation to reveal that the objective is unattainable and the process horrifying. Orlan the artist and the woman will never play the victim: she is both subject and object, actress and director, passive patient and active organizer. This still leaves us with the disquieting question of whether masochism may be a legitimate component of esthetic intention, or whether we are dealing here not with art but with illustrated psychopathology. This is the crucial question in a context in which real and fake, art and anti-art view for attention.

Orlan's medium, finally, is media. If that sounds redundant, she means it to be. Her critical method is based on a sophisticated feedback system, a vicious circle of echoing and self- generating images, spawning a progeny of hybrid media reproductions This continuous feedback loop is difficult to escape long enough to gain sufficient distance to decode the meaning of her performances and their afterlife as documents, relics and replicated image banks. The visceral effect and sensory overload of her imagery, however, are sufficiently alienating to afford the detachment required for judgment and interpretation. She creates esthetic distance through a Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt or alienation effect on which his stylized theater was based. Orlan attacks the Judeo- Christian l tradition of the sacredness of the body and its taboos against mutilation to transgress a boundary as well as to alienate rather than . evoke empathy in the audience.

Because of the interactive nature of contemporary communication systems, whatever is said about an art work becomes attached to it as an additional meaning. So it is altogether appropriate that the article you have just read is actually the work that Orlan will exhibit in the show titled "Is It Art?" curated by Bard College instructor Linda Weintraub.8 Read: Feedback, Recycle, Vicious Circle.

Author: Barbara Rose is a critic and curator.

1. France Borel, Le Vétement Incarné, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1992. Borel considers mutilation, tattooing, scarification, plastic surgery and other bodily interventions within an anthropological context.

2. Vittorio Fagone, "Con il chirugo in cerca de Venere," Il Messaggero, Aug. 13, 1992.

3 Catherine Millet, L'Art Contemporain en France, Paris, Flammarion, 1987.

4 Dr Cherif Zahar, who performed three of the first five operations, describes them in Fiebig-Betuel, "Orlan or Lent" and "Document: Texte pour l'Operation d'Orlan," both articles in VST 23/24, Sept..Dec. 1991.

5. VST, Revue Scienfique et Culturelle de Santé Mentale 23/24, Sept.-Dec. 1991. This entire psychoanalytic publication is dedicated to the relationship of Orlan's work to psychopathology and esthetics and contains articles by psychologists, critics and artists concluding that Orlan's surgery projects are indeed art.

6. Bernard Ceysson, "Saint Orlan: Vingt Ans d'Art et Publicité," exhibition catalogue, Musée St. Etienne, 1989.

7. Orlan's relationship to technology is explored by Gladys Fabre in "Femme sur les barricades: Orlan Brandit le laser," Skai et Sky Video Editions, 1984.

8. The exhibition, "Is It Art?," was scheduled to take place in the fall of 1992 at Bard College's Blum Art Institute, which ceased operations in December [see A.i.A., Jan. '93], causing the show's postponement. It is now in preparation for a later date, in 1993, and plans are in the works for a national tour.